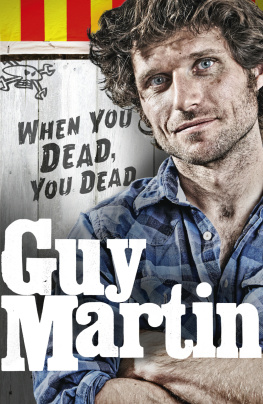

PICKETS AND DEAD MEN

THE MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS

is the nonprofit publishing arm of The Mountaineers Club, an organization founded in 1906 and dedicated to the exploration, preservation, and enjoyment of outdoor and wilderness areas.

1001 SW Klickitat Way, Suite 201, Seattle, WA 98134

2009 by Bree Loewen

All rights reserved

First edition, 2009

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Developmental Editor: Julie Van Pelt

Copy Editor: Carol Poole

Cover Design: Karen Schober

Book Design and Layout: Mayumi Thompson

Cover artwork: Jannelle Loewen

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Loewen, Bree, 1981

Pickets and dead men / by Bree Loewen. 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-59485-101-8

ISBN-10: 1-59485-101-8

1. MountaineeringSearch and rescue operationsWashington (State)Rainier, Mount. 2. Park rangersWashington (State)Mount Rainier National Park. 3. Loewen, Bree, 1981- I. Title.

GV200.183.L63 2009

363.14'09797782dc22

2008028361

Printed on recycled paper

Printed on recycled paper

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

GEORGE BURNS ONCE SAID, No snowflake in an avalanche ever feels responsible. Heres a shout out to all the unique and multifaceted individuals who are responsible for the creation of this book. Thanks to Ted, Adrienne, Tracie, Tom, Paul, Charlie, and the rest of the park folk for giving me the awesome experience of having met and worked with you. You guys have changed my life in so many ways. Thanks to my friends and climbing partners Alice, Ryan, and Russell, who taught me how important grace is in climbing and in life. Thanks to the entire staff of the Mountaineers Books for their time and attention. It was a pleasure to work with Dana Youlin, Mary Metz, Julie Van Pelt, and Carol Poole. Special thanks to Russell for your unfailing support on this project, as well as for marrying me and giving me a child and a small house in the country with nice Adirondack chairs, a big kitchen, and a spot to grow organic peas. Happy endings are the best.

AUTHORS NOTE

I HAVE MADE EVERY EFFORT TO PROVIDE an accurate account of the people, places, and events as relating to my experiences on Rainier. I have relied on my own memory and journals, as well as the memories of friends, family, and fellow rangers. But essentially this is my story, my perspective on my seasons on Rainier. Any gaps in my story or misrepresentation of facts are purely accidental and unintentional. In most cases, I have confirmed or attempted to confirm such details, but there will undoubtedly be a few inconsistencies, for which I apologize in advance. Some individuals names have been changed.

1

DONT GET FROSTBITE

A MONTH INTO MY FIRST SEASON I was interviewed by the Tacoma News Tribune about what it was like to be a girl climbing ranger at Mount Rainier National Park. They wanted to know about my typical day, how many people Id rescued, and what it felt like to kick butt in the mountains wearing a sports bra and floral print shorts. I told them the bra and shorts were buried under too many layers of clothing to be a factor. I said sometimes it was difficult being a woman in the profession, but other things were far more difficult, and then, laughing, I told the reporter I wasnt going to talk about any of it because being a climbing ranger was my dream job and I wanted to keep it.

As I understand it, when I was hired there were several guys who had been volunteering as climbing rangers for years with the expectation that they would get hired as soon as spots opened up. Theyd had a falling out with the boss just before the season started, despite being well-liked and respected by everyone else. Consequently, they were slighted when myself and two other girls with no real experience on the mountain whatsoever were hired in their places.

We three girls had a poor understanding of what we were supposed to be doing on a daily basis. Almost no one wanted to invest the time to teach us how to do our jobs right, and no one expected us to stay very long. In the beginning, I persisted partly because of the glamorous idea of doing high-profile rescues. I wanted to fly around in helicopters and watch my work on the evening news. Mostly, though, I thought shared hardship increased camaraderie, and so the more difficult and stressful rescues I took part in, the less the grudges of the past would matter, and the closer a community my coworkers and I would become. I wanted to create friendships that would last, that I could trust my life to, the kind where we would sit together when we were old and reminisce about all the crazy things wed done.

These friendships never really materialized, but I stayed for years anyway because of my relationship with the public and the beauty of the environment, and because I received a paycheck. Among my coworkers, I was the one who cleaned the bathroom, but when I was the lone ranger on the upper mountain I was the ultimate voice of authority. When people did what I said, they lived, and when they didnt, they died, or at least suffered unreasonably. They didnt always respect my advice at the time, or sometimes ever come to appreciate the unconditional support I gave them, but I knew even the small contributions I was able to provide were making an immediate difference in the lives of inexperienced or unlucky climbers every day. Although these werent the types of relationships I was looking for when I started, I recognized that they were important nonetheless.

This do-gooder desire was combined with my lack of other job prospects. Id graduated from college at seventeen with a philosophy degree, spent the next four years as a climbing bum living in my compact car, and had most recently worked as an ambulance jockey, sleeping on the gurney in the back between unlimited overtime shifts. That was a job that I would have done almost anything not to go back to because I felt like the longer I worked there, the more jaded I became towards the people I was sent to help. I saw starving old people who were afraid to tell anybody, and babies covered in rat bites, along with a litany of things that seemed to me to be worse than death. I saw so much that things that should have bothered me started not to. I didnt want to be numb. I wanted to be compassionate and understanding again, and I wanted my days to be filled with beauty and success.

This left me at age twenty-one with climbing as my only job skill, and Id just had one of the rare, extremely hard-to-get climbing-based jobs dropped in my lap. Here I was, with important work handed to me every day in one of the most beautiful places on earth. I wanted to prove I had what it took to work every day in the mountains, to show that women could excel at this work. I didnt want to blow it.

During my three seasons at Rainier I came to realize that, as much as I wanted to prove myself, in the end I didnt have the skills or stamina to live up to the standards my supervisors, coworkers, and the public set for me, let alone the ones I set for myself.

Even from day one, things were grim. I came into the job with a debilitating reputation to overcome: Id been rescued off Mount Rainier in a highly televised extravaganza less than a month before I got hired to rescue others.

Next page

Printed on recycled paper

Printed on recycled paper