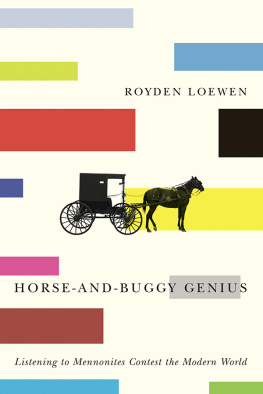

ROYDEN LOEWEN

HORSE-AND-BUGGY GENIUS

Listening to Mennonites Contest the Modern World

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Canada R3T 2M5

uofmpress.ca

Royden Loewen 2016

Printed in Canada

Text printed on chlorine-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper

20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the University of Manitoba Press, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca, or call 1-800-893-5777.

Cover design: David Drummond

Interior design: Jess Koroscil

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Loewen, Royden, 1954, author

Horse-and-buggy genius : listening to Mennonites contest the modern world / Royden Loewen.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-88755-798-9 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-88755-493-3 (pdf )

ISBN 978-0-88755-491-9 (epub)

1. MennonitesAmericaInterviews. 2. MennonitesDoctrines. 3. Civilization, Modern. I. Title.

BX8121.3.L63 2016 230.97 C2015-908003-7

C2015-908004-5

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

The University of Manitoba Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage, Tourism, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

CONTENTS

Preface

This book is based on an oral history project designed by a team of graduate and postgraduate students and me between 2009 and 2012. The subjects of this study are the quiet and reclusive horse-and-buggy Mennonites of Canada and Latin Americathe Canadians known broadly as Old Order Mennonites and the Latin Americans as Old Colony Mennonites. Both groups have been the subject of media accountsnewspapers, magazines, radio, and TVbut not often as the focus of the oral historian. Yet both the Canadian and Latin American groups have their stories to tell: perhaps they have lived out their anti-modern lives in starkly different contexts, but they have faced similar challenges in history.

Thus we went to them looking for answers to the basic question of history and culture: what has changed in the life of your people and how have they survived the test of time. At an inaugural September 2008 workshop on this project in St. Jacobs, Ontario, we as a team pondered the specific questions we would ask these Mennonites. We shared notes of our own research experience and mapped ways of undertaking ethical and culturally sensitive research. We were reminded that often the best approach, one standard in oral history methodology, is to ask open-ended questions. Our goal, after all, was not to create a precise history of Old Colony and Old Order Mennonite communities. Rather, it was to record what members of these communities said they remembered about changes that they had made to preserve their communities within the modern world. Certainly the accuracy of memory assists in creating a credible narrative. However, as oral historians like Alessandro Portelli and others have argued, even imprecise recollections point to the greater truth of an event or past era, for memory is a way of making sense of the present. And ultimately the goal of this book is to convey the historically conditioned culture, the genius, of these quiet and communitarian people to the wider world. That genius, we learned, would not become apparent in stilted question-and-answer sessions.

To enable this project we, as the researchers, sought safe spaces for the interviews. And most did occur in the interviewees own social places: the familiar inner sanctums of their homes, but also on their buggies, in taxis that they hired, in city restaurants that they suggested, or by happenstance in front of the colony general store or on the side of country roads. In the end, the stories the horse-and-buggy people told us in response to our questions were unrehearsed and reflected a world without telephone and Internet where social spontaneity is welcomed. Many interviews were not even planned ahead. Nor were they vetted by local church or community authorities. The result, we hoped, would be stories, uncontrived and told from the heart. Of course, the written transcripts of the interviews, to be deposited in a publicly accessible archive, are filtered documents. They are shaped by the questions we asked, and reflect a long-standing idea that oral history is always a co-production of interviewer and the interviewed, and hence, a social process unto itself.

We were also mindful that the interview transcripts were produced in the social context in which outsiders are distinguished from insiders. The interviewers and research architects for this book were seven committed young scholars, graduate and postgraduate university students (Kerry Fast, Tina Fehr Kehler, Anna Sofia Hedberg, Jakob Huttner, Anne Kok, Andrew Martin, and Karen Warkentin) and me. Trained variously in history, anthropology, sociology, and religious studies, four of these research associates were acculturated Mennonites from Canada, while three were non-Mennonites, one each from Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. The language of conversation in the Latin American communities was usually Low German (but also Spanish, High German and English), while in Canada all interviews were in English. Perhaps the interview process itself was not especially strange to the horse-and-buggy people; given the agrarian culture of the Sunday afternoon or weekday evening visit, telling stories is common in these communities. And, certainly, this cultural divide was bridged in part by the fact that we as interviewers were present, often as overnight guests, usually at meals, recipients of warm hospitality, or in places outside the home they invited us into. Yet, it was always clear that we were not members of the community; indeed, we had come from afar to ask them about their history and communities.

The stories that these Mennonites told us were those they seemed to want to tell. Following ethical guidelines vetted by the University of Winnipeg, where I teach, we made it clear to the interviewees that we were writing a book that would be read by the wider world. We also reminded them that they did not have to talk to us, that they could stop the interview at any time, that they could contact us after the interview to withdraw their remarks, and that they need not allow their names to be used in the book. The majority, especially the Old Colony Mennonites in Latin America, said that we could use their names, a practice that they employ in writing to Mennonite newspapers. The Old Order Mennonites in Canada, who live closer to many potential readers and have a tradition of using pseudonyms in writing in public forums, were more hesitant; thus, in respect of that tradition, they are referred to in this book mostly by culturally appropriate pseudonyms. And reflecting the sensitivity of horse-and-buggy people to modern technologies, only a third of the interviews were tape-recorded, with the rest recorded by hand during the interview or within the day of the interview as field notes.