Design by Dawn J. Ranck

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RUSSIAN MENNONITES

Copyright 2005 by Good Books, Intercourse, PA 17534

International Standard Book Number: 1-56148

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number:

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner, except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, without permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Table of Contents

Introduction

Travel the plains of Kansas in late spring and you will see plenty of wheat. The fields are a wall-to-wall carpet of natural green, laid down by human hands and the forces of nature. Growing there is a special kind of wheat, with hard, protein-rich kernels that make top-quality flour for the best grade of bread.

Kansas Mennonites will be happy to explain how this particular variety of wheat came to mid-America. They will tell you about Anna Barkman, the young immigrant girl who carefully sewed her rag doll full of the hearty kernels before leaving Russia in 1874. They will tell you how those few handfuls of grain became the seed of new life for the first Russian Mennonites who came to North America.

Travel north out of Kansas through Nebraska, the Dakotas, and finally into Manitoba, and you can follow the harvest as it rolls like falling dominoes over the plains. In Manitoba, too, a sturdy agricultural foundation was laid down by Russian Mennonites who came in the 1870s and transformed the prairie into their own version of Eden.

This is their story. It is, first of all, a story of faith, of Anabaptist faith that could not be suppressed. It is also a human story, with cultural and economic dimensions that make the Russian Mennonites unique.

How They Got to Russia

If you visit long enough with Mennonites in places like Kansas or Manitoba, you will eventually hear the term Russian Mennonite. That may sound odd, as the people youre talking with may be third- or fourth-generation North Americans, and may never have been anywhere close to Russia.

What youre hearing distinguishes this type of Mennonite from what are sometimes called Swiss-German Mennonitesan earlier immigrant group who populated Pennsylvania, Virginia, and other places in the eastern parts of North America. The Russian Mennonites (a more accurate term might be Dutch-Russian Mennonites) have last names like Wiebe, Penner, and Friesen and enjoy their own traditional foods like zwieback (double-decker buns) and borscht (cabbage soup). Their ancestors likely spoke plattdeutsch (Low German) at home. You may also pick up slight peculiarities in temperament, in how they worship, and in how they interact with the government and the wider culture (more about that later).

For now, lets just understand that these people descend from north European Mennonites who found their way to Russia in the late 1700s, established their own Mennonite commonwealth there and began emigrating to North America in the 1870s.

A field of sunflowers, a pominent Mennonite crop, in the former colony of Fuerstenland.

But how did they get to the vast steppes of Russia in the first place?

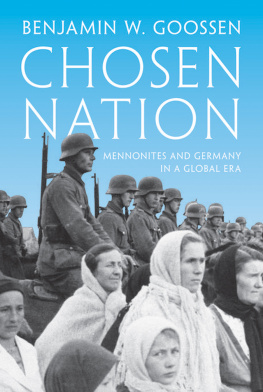

Looking for refuge

The sixteenth century was tough on a new breed of Christians who emerged in Switzerland and Holland during what is called the Radical Reformation. These people believed baptism should be a voluntary step for adult Christians, not something to be forced upon a helpless infant. In 1525 they broke away from the established church and began to practice a voluntary second baptism, and thus were dubbed Anabaptists. Gradually they came to be known as Mennonites, after Menno Simons, a former priest around whose leadership the young movement coalesced.

The Mennonites soon became a spiritual force to be reckoned with across northern Europe. Their new faith, based on an adult choice to become part of the church, was a threat to ecclesiastical leaders who were accustomed to wielding unfettered control with no argument. The authorities took unkindly to these disobedient upstarts, chasing them from one place to another, burning some and drowning others. Those who survived sought refuge wherever they could. Throughout their history, their beliefs, especially their belief that Christians should have no part in making war, made them a people on the move.

In those days, Europe wasnt yet divided into countries as it is today. It had numerous smaller regions governed by princes and other rulers, some of whom were quite strict about the kind of religious beliefs people should have.

Others were more relaxed about religious beliefs, or had more pressing issues to deal with. One such region could be described as Polish-Prussia, known today as Poland. Its ruling princes, as well as the later King Frederick the Great (1740-1786), provided a haven of refuge. They had ulterior motives for welcoming the persecuted Mennonites. For one thing, a flow of new immigrants would replace huge numbers who had been wiped out by the plague. For another, they needed help with water.

Back in Holland the Mennonites had learned a few things about water and how to control it. Now they would find a new outlet for those skills. Polish-Prussia needed land reclaimed from the delta of the Vistula River. The Mennonites flocked there, first of all to Danzig (known today as Gdansk) and then to other areas. They built dikes and reclaimed rich farmland from what had previously been swamps and mud.

In return for their diligent work the newcomers were offered religious tolerance, exemption from military service, and room to grow.

A place to call home

The Mennonites went to work, carving out a new way of livingtogether, and out of harms way. Maybe here they would finally find peace. They formed villages of a couple of dozen families. Besides their farmland, each family had a large garden as well as a few cows and pigs. While they enjoyed being able to keep to themselves, they were open to others who found their faith and lifestyle attractive, people with Polish names like Sawatsky, Rogalsky, and Pankratz.

The Lutheran church leaders, who dominated the town councils, werent fond of the Mennonites. They were jealous of how the resilient newcomers could rebound from any setback and flourish wherever they were planted. After Frederick the Great died in 1786, pressure on the Mennonites grew. Special taxes were levied, some of which went to support the military. Restrictive laws were passed to keep them from buying land, which meant growing families couldnt expand their farms.

Farming was still the Mennonites dominant livelihood, but many were merchants, weavers, and artisans. Even they felt the press of restrictions. Mennonites were prevented from joining professional guilds. Thus the art of clockmaking, for example, at which Mennonites excelled, became an underground industry.

Once again, the Mennonites felt pressure from a combination of political, economic, and religious forces. While not openly persecuted, they were clearly secondclass citizens. And things would likely get worse. Europe was in upheaval as a result of the French Revolution. As nervous regions bolstered their defenses, Mennonite leaders and parents wondered how long their young men would be spared from military involvement.

Many started looking northward to the huge new frontier of Russia, where Czarina Catherine the Great was opening wide her arms to foreigners of many stripes.