CHOSEN NATION

CHOSEN NATION

MENNONITES AND GERMANY IN A GLOBAL ERA

BENJAMIN W. GOOSSEN

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

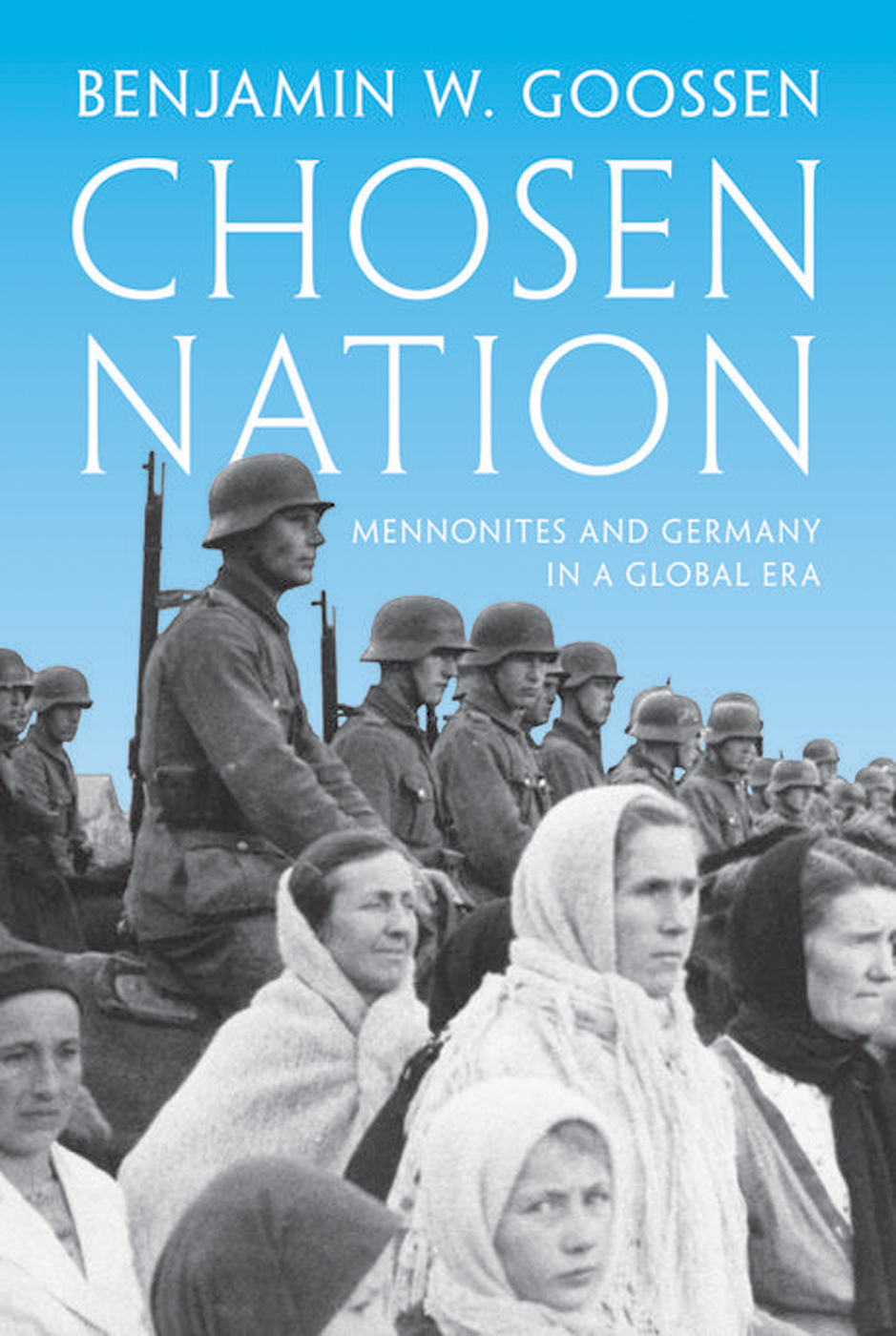

Jacket photograph: Residents of the Molotschna Mennonite colony in southeastern Ukraine, including a cavalry squadron under the Waffen-SS, celebrate a visit from Heinrich Himmler, 1942. Courtesy of The Mennonite Heritage Centre, Winnipeg, Alber Photograph Collection 351-9

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-17428-0

Library of Congress Control Number 2017930424

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon Next LT Pro and Penumbra Half Serif

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

FOR MY FAMILY

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I spent the first years of my life in a small Mennonite town in central Kansas. Pacifist Mennonites had settled the Great Plains during the 1870s, when thousands left Europe to escape newly established conscription laws. While most of these immigrants came from colonies in southern Russia, several hundred also left the German region of West Prussia. Among these were the ancestors of my paternal grandfather, Henry Goossen. I knew my grand father as a thoughtful and congenial man, a retired minister who always arrived at church a half hour early and who habitually proclaimed himself a proud Prussian. My fascination for what I considered the profound irony of my grandfathers dual identityas a Mennonite and a German Americanprompted me to undertake this study. The greatest ideals of Mennonitism, according to my understanding, were personal humility and the notion that ones highest allegiance should be paid to God. Germanness, by contrast, signaled pride and loyalty to an earthly nation. In the abstract, I found the two concepts irreconcilable. And yet, in the figure of my grandfather, I could not read one without the other.

My search took me to archives and historic sites across the Atlantic world. From the birth town of Menno Simons to the oldest standing Mennonite church, I visited places I had heard about since childhood. Traveling to rural parsonages, farmsteads, and cemeteries, as well as to Reformation-era sites of baptism, persecution, and hidden worship, I followed paths well-trodden by Mennonite pilgrims since the late nineteenth century. In congregations throughout Europe and the Americas, I encountered incredible hospitality and friendship, as well as many more stolze Preuen. My travels helped me both to understand contemporary Mennonites and to reconstruct the spatial world of earlier generations. Yet they also taught me I was asking only half the question I needed to pose. While I had set out to discover the influence of German nationalism upon Mennonites, I became increasingly skeptical that Mennonitism itself constituted a coherent historical category. At least as I had absorbed it as a child, the story of the Mennonites was a nationalist narrative in its own right.

As is so often true of Mennonite projects, this book has been a community effort. I would like to thank those who made it possible through their encouragement and support. Fellowships from the German Academic Exchange Service, the Fulbright Commission, Swarthmore College, and Harvard University enabled research at home and abroad. The scope and shape of my project emerged from significant exchanges with Mark Jantzen and John Thiesen. I am grateful to Abraham Friesen for allowing me to use personal research materials; both Peter Letkemann and James Urry have shared their expertise on Imperial Russia and its successor states, as well as many unpublished documents. Conversations with Fernando Enns have informed my thinking about Mennonite peace theology. Robert Kreider has been a tireless conversation partner; his wisdom and enthusiasm for Anabaptism have been models for me.

I have received hospitality and assistance from many scholars and Mennonites. In Weierhof, Gary Waltner far exceeded his role as head of the Mennonite Research Center by sharing with me his home, culinary skills, and boundless knowledge of all things Mennonite. I thank Gary for the hours we spent discussing history and theology while sorting currants, savoring Mohnkuchen, and traveling to churches around Germany. Thanks also to my fellow researchers in Weierhof, including Hans-Joachim Wien, Joachim Schowalter, Horst Gerlach, and Ortwin Driedger, for sharing their findings. Sonja Bartel, Manuela Bolick, Gundolf Niebuhr, Frank Peachey, Astrid von Schlachta, Conrad Stoesz, and Tillie Yoder helped me navigate archival collections on both sides of the Atlantic. I fondly remember an afternoon at the Bienenberg with Hanspeter Jecker, as a well as a tour he conducted in Bern as part of the Mennonite European Regional Conference. In Strasbourg, the staff of Mennonite World Conference shared information on transnational Anabaptist organizations from the sixteenth century to the present, and in Detmold, Krefeld, and Mnster, the German Mennonite Historical Society sponsored fascinating sessions.

For their perspectives, I am indebted to Alfred Neufeld in Asuncin; Benjamin and Wolfgang Krau in Bammental; Jacob Thiessen in Basel; Ingrid and Horst Kger in Berlin; Irina und Heinrich Unrau in Bielefeld; Francisca and Uwe Friesen in Ebenfeld; Alex Teichreb in Emmendingen; Christel and Wolfgang Schultz in Falkensee; Lydia, Viktor, Naemi, and Luise Fast as well as Erich Dyck in Frankenthal; Isabell Mans, Corinna Schmidt, Bernhard Thiessen, Maren Schamp-Wiebe, Thomas, Sam, Tabea, and Janneke Schamp in Hamburg; Gabrielle Harder in Krefeld; Hannah Rosenfeld, Marius van Hoogstraten, Anne Hege, and Rebekka Sauer in Neuklln; Justina Neufeld and Floyd Bartel in North Newton; Eva, Johannes, and Matthias Dyck in Oerlinghausen; Brenna Steury Graber, Brad Graber, and Valentin dos Santos in Paris; and Cor Trompetter in Wolvega. All of these individuals as well as their families made me welcome in their homes and shared resources on Mennonite history. With appreciation for their hospitality, generosity, and sheer love of life, I thank Evi and Dieter Volpert, in whose home much of this book was written.

I have been blessed with learning environments that foster both academic scholarship and personal growth. At Swarthmore College, Universitt Freiburg, Freie Universitt Berlin, and Harvard University, students, professors, and alumni have been amazing resources on a daily basis. Elke Plaxton, Sunka Simon, and Hansjakob Werlen instilled in me a love of German literature and language; Timothy Burke, Allison Dorsey, and Robert Weinberg deepened my thinking on the craft of historiography; and George Lakey, Ellen Ross, Joyce Tompkins, and Mark Wallace encouraged my interest in Anabaptism. Randall Exon taught me more about art, including the art of German history, than he knows. Arnd Bauerkmper and Sebastian Conrad facilitated research in Germany. During presentations at Harvard University, Swarthmore College, the University of Winnipeg, Universidade de So Paulo, the German Studies Association, Mennonite World Conference, and numerous churches, audiences offered valuable suggestions. Special thanks to Miriam Rich, who encouraged me to engage issues of gender, and to Benjamin Van Zee, whose conversation and excellent restaurant choices enlivened winter in Berlin.

This study began as a thesis for the Swarthmore College Honors Program, and I am indebted to Helmut Walser Smith for agreeing to be my examiner. For her willingness to jump into this project partway through, I thank Alison Frank Johnson, whose vision and careful readings helped me see Mennonitism for the vibrant, pluralistic religion it is. Tara Zahra has offered masterful commentary on every chapter; these pages aspire to the elegance of her own writing. I am grateful for suggestions from Celia Applegate, Leora Auslander, Sven Beckert, David Blackbourn, James Casteel, John Eicher, Marlene Epp, Helmut Foth, Michael Geyer, Hans-Jrgen Goertz, Peter Gordon, Faith Hillis, Andrea Komlosy, Diether Gtz Lichdi, Royden Loewen, Charles Maier, Terry Martin, Kelly ONeill, Moishe Postone, John Roth, Walter Sawatsky, Steve Schroeder, Nathan Stoltzfus, Ajantha Subramanian, Paul Toews, Heidi Tworek, and Hans Werner. At Princeton University Press, Quinn Fusting and Brigitta van Rheinberg have made publication a rewarding process. Three anonymous reviewers provided stimulating, incisive feedback. As the main advisor to this project, Pieter Judson has been an outstanding teacher, mentor, and friend. His guidance has pushed me to think deeply about nationality and indifference to nation while allowing me to pursue my own course. I thank Pieter for discussing the connections between scholarship and activism, for asking about my faith, and for commiserating over the indecipherability of old German script. Pieter has greatly improved the nuance of my argumentation, and I have been inspired by his passion for history.

Next page