Cynthia Levine. Copyright Divine Entertainment

I grew up in a dirty little steel town called Steubenville, in eastern Ohio. It was one of those places where everyone was old, or just plain seemed like it. Even the kids felt the times, and the times were tough.

The streets were narrow and filled with men in Levis with metal lunch boxes coming and going to the mills and the coal mines. It seemed like there was a railroad crossing on every other street, where coils of steel were piled up high along the tracks like giant gleaming snakes resting in the sun. It got real hot in the summertime and the dust from the mills wrapped around the people and held them firmly in their places, and the echo of coughing miners was so common you just didnt hear it.

The local bar, Lou Annes, was always hopping. It wasnt odd to see your neighbor howling at the moon, and every now and then some of the miners would wander down for a cold one and tie their horses to the stop sign. Drinking was a hobby in that little town, and as in a lot of small towns, everyone knew everyone elses business. Women had not quite yet been liberated. Husbands ruled the house, women cleaned it, and any strong female opinion was often rewarded with a fat lip. But no one thought much about that.

At seventeen years old, all my mother, Patricia, ever wanted was to escape. She was born in Pennsylvania in the late 1940s, and her dad took off to California and left her and her mother alone. They moved around from place to place, and after a while she had a new stepdad and two half brothers and sisters. Never fully welcomed into this second family, she found comfort and a home at her grandmothers house.

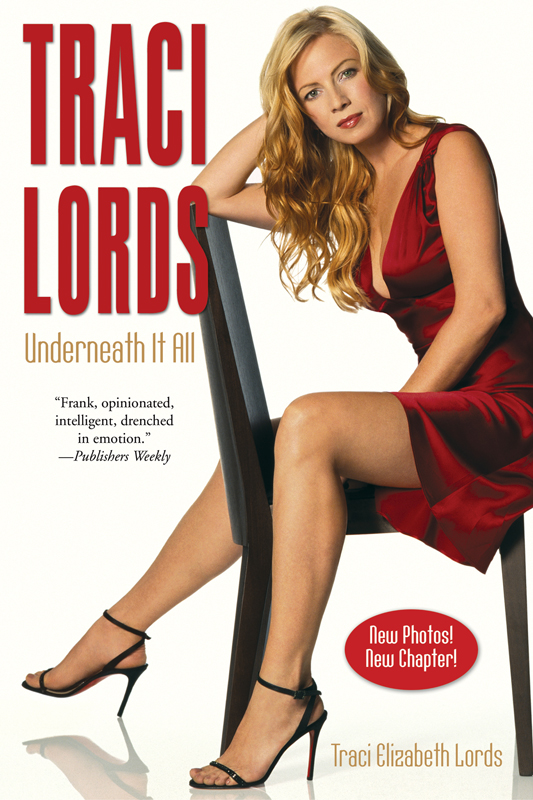

My mother, Patricia, holds me, 1968.

The collection of Traci Lords

My great-grandma Harris was a little redheaded Irish woman who loved sugar-toast and drank tea all day long, no matter how hot it was. She combined a fierce sense of social justice with an almost patrician gentleness that was unusual to find in the government housing project where she lived.

The projects were cockroach-ridden matchbox-shaped dwellings inhabited by desperately poor black families who barely survived on meager monthly public assistance checks. It was a place where hungry children played in the gutters of potholed streets while munching on sandwiches of Wonder bread and mayonnaise they dubbed welfare burgers.

Just a pebbles throw away down the hill was the University of Ohio, where professors drove their shiny new cars to garden fund-raisers on the campus lawn. I remember catching glimpses of white tablecloths blowing in the afternoon breeze while ladies in crisp white dresses sipped drinks from tall glasses. Every once in a while a burst of applause from the appreciative anthill of university people would enter our world. My mouth watered at the scent of cooking barbecue meat, and I longed to race down the hill and devour the mountain of food on the huge banquet tables.

But my mother explained that people like us dont mix with people like those. People like what? I demanded, meeting the weary look of my mother, who said it was a matter of social class. I was five years old at the time and didnt understand why I wasnt one of the chosen few who could receive hot meals and pretty dresses. I only knew that some people had food and others didnt, and I was on the wrong side of the fence. Id gather crab apples from my great-grannys yard and hurl them in protest toward the happy people down the hill. Although my targets were never struck, I felt justice had been served.

Great-grandma Harris lived in the first brick building at the beginning of the housing projects. There must have been fifty other little red houses, winding around like a figure eight, each one containing four units. Grandma was known by her neighbors as the crazy white witch because she was something of a mind reader who had a reputation for being very accurate. People didnt always like what they were told, but their fear kept Grandma safe in a very dodgy neighborhood where racism was a sickening fact of life. Despite it all, my great-grandma was always light, gentle, and seemingly unaffected by her status and the people around her. My mother got a lot of love in that house, and ultimately so did I.

In 1965 the Vietnam War had cast a spell over the people of Steubenville, inspiring in them a patriotic fervor. My mother was a beautiful redheaded teenager with piercing green eyes and a peaches-and-cream complexion. Though she was smart and ambitious, she found herself stuck, working in a jewelry store in a town that celebrated everything she loathed. She thought the war was immoral and said so to anyone who would listen.

An independent thinker, she didnt buy the be a virgin, go to church, follow the establishment routine that a lot of her friends were falling into. She liked to dance, listened to the Stones and Bob Dylan, and filled her private notebooks with poems. She played the guitar, made out with boys at the drive-in, and went roller-skating on Saturday nights. She lived her life fully but was always hungry for a bigger bite.

The war weighed heavily on my mothers heart because it touched her as it inevitably touched everyone. She watched as her friends brothers marched off to a foreign land, and cried like everyone else did when they didnt come back. She ached to have a voice, to make a difference, and to be seen and valued. But she was dead broke and depressed at her lack of opportunities, and no matter which way she looked at it, her future appeared grim. Though she desperately wanted to go to college, she had only managed to get a GED and a crappy part-time job. Her father, who lived in San Diego and hadnt seen her since she was a young child, promised her a place to stay if she came out west, but he did nothing to help her realize her dreams.

My fathers family, the Kuzmas, left the Ukraine in the 1930s and settled in Weirton, West Virginia. I suppose my grandfather wanted the same thing all immigrants do, a better life for himself and his family, so he bought a little house by a creek in Weirton and raised three sons and a daughter there.

My grandfather John had a thick Russian accent and a fierce work ethic that he drilled into his boys. His wife, Mary, was a stout five-footer who drank Pabst Blue Ribbon out of a big blue bowl and sang Russian songs at the top of her lungs while cooking up batches of pierogi and borscht.

My father, Louis, was born with double pneumonia and spent the first weeks of his existence in the hospital fighting for his life. He grew into a young man who dreamed of California and loathed the war. Rejected from the draft because of the scar tissue on his lungs left from the pneumonia, he ended up doing time at the steel mill instead. He also started to study biology at Morgantown College in Pennsylvania but found it difficult to work at the mill and get an education at the same time. Overwhelmed and exhausted, he dropped out and went home to live with his parents.

Im told it was a gorgeous summer day when Louis Kuzma first spied my mom standing on a corner waiting for the light to change in downtown Steubenville. Patricia was on her way to work and had neither time nor patience for the handsome stranger who was trying to pick her up. But he followed her for several blocks, rambling on about the weather and how it was so nice to see her again. He acted like she already belonged to him. She was about a second away from telling him to take a flying leap, but something stopped her. He was a real looker, my dad, with his baby blue Clint Eastwood eyes, honey-dipped skin, and a thick head of sandy blond hair. It wasnt just his looks that got to her, however. It was the kindred spirits he saw in him.