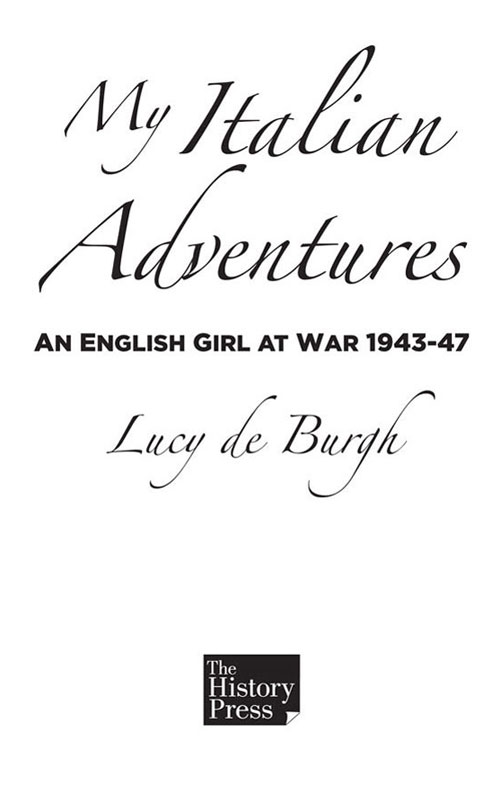

Lucy de Burgh - My Italian adventures: an English girl at war 1943-47

Here you can read online Lucy de Burgh - My Italian adventures: an English girl at war 1943-47 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: The History Press, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:My Italian adventures: an English girl at war 1943-47

- Author:

- Publisher:The History Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

My Italian adventures: an English girl at war 1943-47: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "My Italian adventures: an English girl at war 1943-47" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

My Italian adventures: an English girl at war 1943-47 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "My Italian adventures: an English girl at war 1943-47" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Cover image: Authors collection.

Martino Trust

I n September 1943, after Italy signed an armistice, tens of thousands of Allied prisoners of war sought to make good their opportunity to escape from captivity and recapture by the Germans.

The author of this book, Lucy de Burgh ( ne Addey), has donated her royalties to the Monte San Martino Trust, a charity established to commemorate the bravery of those Italians who assisted the fugitives.

Lucy Addey was the intelligence officer in the Allied Screening Commission, which investigated the fate of those fugitives after the Allied invasion of Italy. She later married its commanding officer, who had himself been helped following his own escape from Fontanellato Camp, near Parma. Their admiration for the Italians whom the Trust seeks to remember is recorded in this book.

The Monte San Martino Trust is named after a small village in the Marche region of Italy, as a tribute to the villagers, who were amongst the first to help the founder of the organisation, Keith Killby, and many others.

The Italians, many of them extremely poor farmers, shared what little food they had, provided clothing and shelter, and generally did what they could to help the escapers on their way. In doing so, they risked imprisonment and the loss of their property. Many even paid with their lives.

Every summer, the Trust brings twenty young Italians to England for a month to learn English, in Oxford and London, and to experience the British way of life. The students come from the regions of Italy where escaping prisoners found refuge, and many of them come from families who themselves sheltered prisoners and possess Alexander Certificates to prove it.

The Trust links the escapers, and their descendants, with the Italian families by organising fundraising events and commemorative trails in Italy. The Trust also has an archive of 100 POW manuscript diaries and books, an important source for historians of the period, and a priceless memorial to some very brave Italians, and their kindness to strangers.

My own father was also in Fontanellato Camp, and owed his own eventual safe return to the many families who sheltered him and, in particular, to two Italian partisans who died helping him cross the final mountain range.

The Trust (registered charity No.1113897) relies entirely on donations to carry out its work. If you would like further information, or if you would like to make a donation, please visit our website www.msmtrust.org.uk

Sir Nicholas Young

Chairman, Monte San Martino Trust

Chief Executive, The Red Cross

London, August 2012

M any twenty-first century people who are not Italian merely have a vague notion of Mussolinis Italy during the war as a Fascist state that was a bungling accessory to Hitlers tyranny. In truth, as historians know, the principal victims of Mussolinis grotesque political and imperialistic pretensions were his own people. If he had preserved Italian neutrality in 1940, instead of plunging into the war in hopes of a share of Nazi booty, I believe that he might have sustained his dictatorship for many years in the same fashion as General Franco of Spain, who presided over more mass murders than the Duce, yet was eventually welcomed into membership of NATO. It is unlikely that Hitler would have invaded Italy merely because Mussolini clung to non-belligerent status; the country had nothing Nazi Germany valued. As it was, however, between 1940 and 1945 the catastrophic consequences of adherence to the Axis were visited upon Italy. What I mostly want to do here is to offer a brief narrative of what ordinary Italian people suffered in the war, especially in its last two years.

Italys surrender in 1943 precipitated a mass migration of British POWs, set free from camps in the north to undertake treks down the Apennines towards the Allied lines. A defining characteristic of such odysseys, many of which lasted months, was the succour such men received. Peasant kindness was prompted by an instinctive human sympathy, rather than by any great ideological enthusiasm for the Allied cause, and it deeply moved its beneficiaries. The Germans punished civilians who assisted escapers by the destruction of their homes, and often by death. Yet sanctions proved ineffectual: thousands of British soldiers were sheltered by tens of thousands of Italian country folk whose courage and charity represented, I suggest, the noblest aspect of Italys unhappy role in the war. A young Canadian soldier, Farley Mowat, arrived in the country with a contempt for its people. But he changed his mind after living among them. Mowat wrote home from a foxhole below Monte Cassino:

it turns out theyre the ones who are really the salt of the earth. The ordinary folk, that is. They have to work so hard to stay alive its a wonder they arent as sour as green lemons, but instead theyre full of fun and laughter. Theyre also tough as hell They ought to hate our guts as much as Jerrys but the only ones I wouldnt trust are the priests and lawyers.

For many months even before Marshal Badoglios government surrendered to the Allies, his fellow-countrymen saw themselves not as belligerents, but instead as helpless victims. The American-born writer Iris Origo, living in a castello in Tuscany with her Italian husband, wrote in her diary:

It is... necessary to realize how widespread is the conviction among Italians that the war was a calamity imposed upon them by German forces in no sense the will of the Italian people, and therefore something for which they cannot be held responsible.

The Italians overthrow of Mussolini and declaration of war on Germany in October 1943, far from bringing a cessation of bloodshed and freeing their country to embrace the Allies, exposed it to devastation at the hands of both warring armies. The view of many Italians about their nations change of allegiance, and about the Germans, was expressed in a letter one man wrote two days later: I wont fight on their side nor against them, although I think them disgusting. Iris Origo noted: The great mass of Italians tira a campare just rub along. Emanuele Artom, a member of a Torinese Jewish intellectual resistance group, wrote:

Half Italy is German, half is English and there is no longer an Italian Italy. There are those who have taken off their uniforms to flee the Germans; there are those who are worried about how they will support themselves; and finally there are those who announce that now is the moment of choice, to go to war against a new enemy.

Artom himself was captured, tortured and executed in the following year.

Nazi repression and fear of being deported to Germany for forced labour provoked a dramatic growth of partisan activity, especially in the north of Italy. Young men took to the mountains and pursued lives of semi-banditry: by the wars end, at least 150,000 Italians were under arms as guerrillas. Political divisions caused factional warfare in many areas, notably between Royalists and Communists. Some Fascists continued to fight alongside the Germans, while the Allies raised their own Italian units to reinforce the overstretched Anglo-American armies. Italians were united only in their desperate desire for all the belligerents to quit their shores.

Instead, their agony persisted and deepened. In June 1944, amid the euphoria of the Allied armies advance on Rome, the commander-in-chief General Sir Harold Alexander made a gravely ill-judged radio broadcast appeal to Italys partisans, calling on them to rise in arms against the Germans. Many communities consequently suffered savage repression, when the Allied breakthrough proved inconclusive. After the war, Italians compared Anglo-American incitement to a partisan revolt, followed by the subsequent abandonment of the population to retribution, with the Russians failure to succour Warsaw during its equally disastrous Warsaw Rising in the autumn of 1944. The lesson was indeed the same: Allied commanders who promoted guerrilla warfare behind the Axis lines accepted a heavy moral responsibility for the horrors that followed.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «My Italian adventures: an English girl at war 1943-47»

Look at similar books to My Italian adventures: an English girl at war 1943-47. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book My Italian adventures: an English girl at war 1943-47 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.