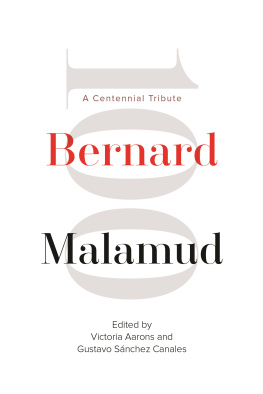

Bernard Malamud

A Writers Life

Bernard Malamud

A Writers Life

PHILIP DAVIS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Philip Davis 2007

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

Typeset by Laserwords Private Limited, Chennai, India

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

Clays Ltd, St. Ives plc

ISBN 9780199270095

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

In memory of Bernard Malamud

The Human Sentence

Preface

It was a graduation day at the University of Liverpool in the summer of 2002. After the ceremony I was talking to the biographer and literary critic Hermione Lee. Now Goldsmiths Professor of English Literature at Oxford, she had once been a lecturer in the School of English at Liverpool and had come back on this day to receive an honorary degree. I said to her that I had seen an advertisement a few months earlier for a conference in Oxford on biography, featuring, amongst others, herself and the daughter of Bernard Malamud. Was Janna Malamud Smith going to write her fathers biography, I asked, because I really wanted to read that book. She looked startled and said she had only just returned from Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she had spoken to the Malamud family. They are now looking for a biographer. For years, since Malamuds death in 1986, the family had resisted the writing of his life. Now they were concerned that his name was fading, his readership and literary standing in danger of decline. Why dont you write it?

I had written about Malamud in a book called The Experience of Reading, published in 1992 and again in an experimental mixture of literary criticism and short stories entitled Malamuds People in 1995. But I had been reading Malamuds work, with a passion, since 1969 when my schoolteacher, the novelist Stanley Middleton, told me to read The Fixer. I remember exactly where I was standing when a friend of mine told me that Malamud had died that day, and I thought, simply: I shall never meet him now.

The conversation with Hermione Lee was a moment of sheer chance. What followed from her suggestion and then introduction was a series of informal meetings with the Malamud family, first with Janna Malamud Smith and her husband David Smith in London, later on in that summer of 2002; then in the November, in the supportive company of my wife Jane, interviews with Malamuds own wife Ann Malamud, in Cambridge, with Tim Seldes (Malamuds agent and one of the literary executors) in New York, and with Paul Malamud, the son, over the telephone in Washington, DC. It was decided that I would indeed write the first-ever biography; that it would be primarily a literary life, as the life of Malamud indeed was; and that it would not be an authorized biography as such, but one written with the full cooperation of the family and estate, without censorship. Let me say here that I am more than conventionally grateful for the generosity of Ann Malamud, Janna Malamud Smith, and Paul Malamudwho in their different ways have been equally and entirely supportive, whilst knowing all the time that not everything I was going to write would please them. But they knew I loved the work. I have thought of them while I was writinga man from the wrong side of the Atlantic, given unlimited and unconditional access, always hoped he was doing justice to the project they entrusted to him. To them above all, as well as to Hermione Lee and Tim Seldes, I owe this book.

Anyone turning biographer, wrote Freud, has committed himself to lies, to concealment, to hypocrisy, to flattery, and even to hiding his own lack of understanding: for biographical truth is not to be had, and even if it were it couldnt be useful. It is a sentence that Malamud, a great reader of biographies, quoted twiceonce in a paper he gave to a group of New York psychoanalysts on Walter Jackson Bates life of Samuel Johnson; again in Dubins Lives where it is said, in chapter 8, that that sentence of Freuds devastated Dubin the biographer.

This particular biographer, myself, has had two aims in writing this book, Freuds warning notwithstanding. The first has been to place the work above the lifebut to show how the life worked very hard to turn itself into that achievement. Too often where Malamud is still remembered, it is for a handful of great short stories; but wonderful as many of those stories are, I want most of all to make the case that Malamud himself most favouredthe case for the novels. But in any event I seek more recognition and more readers for Malamud in the future. In some concluding remarks made at the memorial service for Malamud in Bennington, Vermont, 17 May 1986, Claude Fredericks asked his audience to remember that we, as human beings, are, all of us, nothing other than what we think and that what we think are words and that the words he thought we still have, even though he himself is gone. I have tried to do justice to those thoughts by doing something more than merely summarizing the works: in the case of The Assistant and Dubins Lives they occupy whole chapters; elsewhere, distinct and often concluding or climactic sections.

Whether we are finally nothing other than what we think, I also wanted to tell the as-it-were physical story of Malamuds life, as a struggling and damaged, second-generation, self-made man in America. Thus my second objective has been to show serious readers all that it means to be a serious writer, possessed of an almost religious sense of vocationin terms of both the uses of and the costs to an ordinary human life. When Stanley Eskins wife Barbara asked Malamud if he was working on anything, his answer bore his characteristic mark: Of course; its a way of life. It was also a means of self-education, in the broadest sense: the story of learning from life and in art.

That is why this biography is called

Next page