Contents

Guide

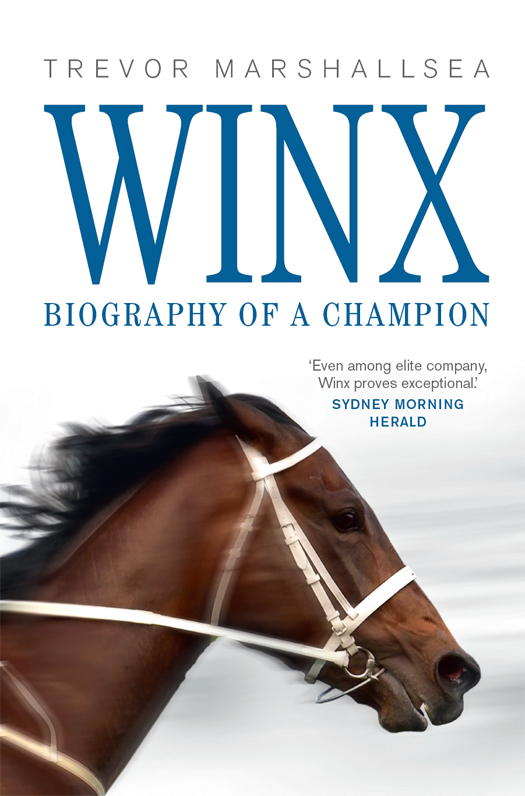

TREVOR MARSHALLSEA is a much-travelled author, journalist and racing lover.

He is fortunate enough to be able to recall the precise moment he was captivated by the turf as a boy when the ABC TV annoyingly switched from the footy to Rosehill one winter Saturday, and a horse with the wonderful name of Wotta Krakka sprouted wings in the straight and won.

It sparked a fascination with the sport that led to his first job as a racing writer, before a wider journalistic career in which he was an Australian Associated Press foreign correspondent in Beijing and London, along with stints in Canada and Hobart.

After six years as chief cricket writer for the Sydney Morning Herald, and several years as a freelance writer, humourist, screenwriter, stay-at-home dad and frustrated punter, he returned to his first love by co-authoring the autobiography of the trainer of the great Black Caviar: Peter Moodys A Long Way from Wyandra.

Trevor lives with his wife and two daughters in Sydney, gets up in the middle of the night to fulfil another lifelong passion of watching Leicester City, and works at home with a small dog at his feet.

A Long Way from Wyandra with Peter Moody

For Lani, Evie, Stef, Val and Warwick

SUDDENLY, WITH THE CRITICAL moment fast approaching where the race would be won or lost, the dominant emotion was despair. For Winx, the mare whod made the impossible achievable, now came the unthinkable. Her streak looked surely over. With such a disarming absence of warning, a racing story that had gripped turf followers and had now begun to enthral a nation, appeared set to be brought to a shuddering, dispiriting halt.

Watching amid the almost unbearable tension, trainer Chris Waller swallowed hard, and grappled with the depression of defeat. On the track, jockey Hugh Bowman rode with an ever-building sense of desperation.

As she strived to create more Australian turf history in one of its grandest races the Doncaster Mile at Royal Randwick, on 2 April 2016 Winxs captivating sequence, then standing at eight straight wins, looked destined to end in anticlimax.

No one could have foretold it would finish this way not the horses trainer, her jockey, or her owners whod ridden such a breathtaking wave of success; not the bookmakers whod sent her out once again as a red-hot favourite; not the growing legion of fans, both ardent and casual, whod been uplifted by a peoples horse called Winx. And to think it would all come undone like this in one of the most illustrious, time-honoured events on the Australian calendar.

In a country where horse racing has a far bigger presence than in any other, Winx had seized imaginations. From muddled beginnings, when she took time to grow into her skin, the daughter of Street Cry and Vegas Showgirl had come from behind, literally and figuratively, developing a knack for flying home from the rear in her races to whoosh past some of the best horses in training. Though nothing extraordinary to look at, a mare of average size and stride, she had left racing lovers amazed by her finishing bursts. She had left jockeys who had felt her power beneath them in awe. She had won the Cox Plate, one of the toughest races in the world, with ridiculous ease and in record time. So soon after the unbeaten Black Caviar whod retired just a year and seven weeks before Winxs first start were we about to be spoiled by witnessing another star of the ages in our time?

Victory in a race like the Doncaster in only her nineteenth start would have gone a long way to confirming Winxs champion status.

But far away from the grandstands where her fans eagerly waited to cheer in the bay mare once more, at the back of the historic Randwick course where the likes of Phar Lap, Tulloch, Kingston Town and Black Caviar had raced into immortality in years past, the man on Winxs back knew something was wrong.

Bowman, the gifted horseman from the bush whod conquered Sydney racing and become entwined with the most exciting horse in the land, had felt the strength and speed of Winx eight times before. He knew her smooth action, her effortless acceleration, and her ability to put herself in her preferred position, settle into a galloping rhythm and wait to pounce on, or to simply overwhelm, her rivals. But on this day, approaching the corner into Randwicks High Street side, with some 1000 metres to go Bowman knew the engine inside Winx was missing a beat.

Waller, the other man who knew Winx intimately, could feel it too. He was watching from his preferred position by himself, on a TV, in a small room under the members grandstand. After his rise from a small town in New Zealand to become one of the biggest trainers in the world, hed come to like it that way tucked away during races to watch and not be watched. Becoming a gargantuan trainer, with several hundred horses on your books, brings success and pressure; training, and watching, a horse like Winx brings more pressure still. As the weight of expectation built with each of her starts, Waller would enter racecourses with a knot in his stomach like hed never felt before. On this day, watching as the field passed the 800-metre mark, he felt physically sick. He could see Bowman was riding the mare. Normally the jockey would just sit there, like a man in an armchair. But now he was urging her along with hands and heels, asking for an effort that just wasnt coming.

Worse still, as the field rounded the home turn with only 450 metres to go, Winx almost disappeared from view altogether. Usually she had the power to ease wide of the pack and shoot home in clear running. But here she was, stuck near the back, still behind a cluster of horses. At least shed started to hit top speed, but amid the chaos of a fifteen-horse charge for home, there was nowhere to go.

Desperate, Bowman looked left and right. All he could see were rumps.

In his private sanctuary, Waller clenched his whole body, then resigned himself to cold reality, a gut-wrenching feeling sweeping through him as he faced up to what he knew, eventually, had to come. Todays the day, he said.

Across a packed Randwick racecourse, and in pubs and homes across the country, the fans held their breath.

AT HALF-PAST NINE ON the morning of 14 September 2011, as the last wisps of fog lifted from the lush green hills of Australias horse country in the Hunter Valley, springs blossoming of life brought forth a new foal. It was a smooth, trouble-free birth. The mare had been through this once before, and there was nothing remarkable to this start of a new life which came, as nature intends, at the start of a new day.

Other than pedigree, horse breeders at this stage dont know anything about a newborn, just like human parents. A baby could become a poet, a prime minister, or a fool. This thoroughbred filly was designed to be a racehorse hopefully a good one. The racing world at that time was agog about another female whod won her first thirteen starts, Black Caviar. Dreams are free.

A new foal could also be one of natures duds. One of the many, the unheard-from majority, who will never win a race. One of the dreaded number who somehow arent put together to run particularly fast, or who through various misfortunes will never even see a racetrack.

But from the first minutes this bundle of gangly limbs and brown fluff spent out of her mothers womb, there was at least something to go on: a tiny glimmer. Most foals will sit on the ground, taking in their new world for a good half-hour before attempting their first steps.

This filly was on her feet in less than ten minutes.

It raised the odd eyebrow, drew measured nods of approval from the seasoned horse people watching. So too her preparedness from very early on to stroll from her mother and explore the corners of her paddock, showing inquisitiveness, confidence and spirit. It was a good sign, a hint that this one had some go in her.

Next page