Published by Da Capo Press, Inc.

Perseus Books is a member of the Perseus Books Group.

FOREWORD

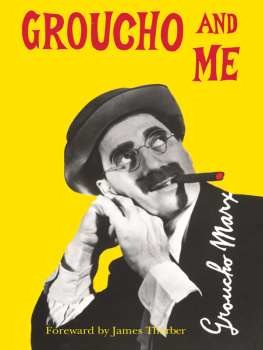

M ore than twenty years ago my wife and I were entertained at dinner in London by an American diplomat and his wife. It was black tie, of course, and I had steeled myself for an evening of polite conversation. Instead, our host took us to see the smartest show in town and the hardest to get in to, the Marx Brothers A Day at the Races. Two years later, in Hollywood, I met the protean author of Groucho and Me, and Ill be darned if we were not, within five minutes, engaged in a serious discussion of Henry James ghost story, The Jolly Corner.

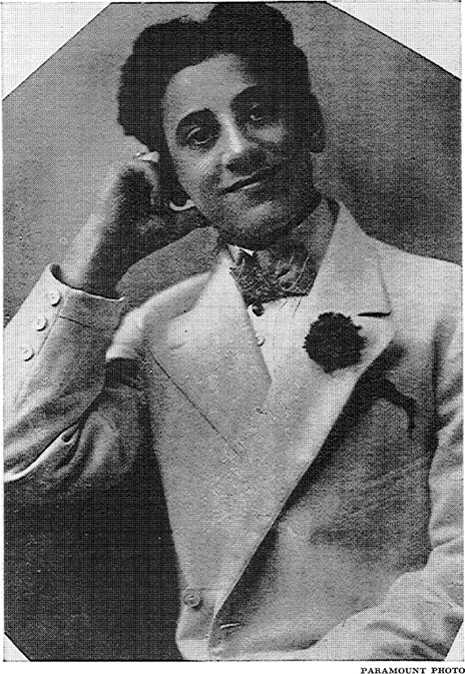

There is nothing ghostly or ghosted about Groucho and Me. The Me is a comparatively unknown Marx named Julius Henry Marx. Groucho and Julius are one, but not the same. The latter is a writer from way back. When The New Yorker was six weeks old, in April 1925, it printed the first of four short casuals that year, signed Julius H. Marx. In 1929 there were three more pieces in the magazine, this time signed Groucho Marx. I think Harold Ross had insisted that Groucho come out from behind his real name and admit, you might say, who he wasnt.

Julius-Grouchos New Yorker pieces consisted of anecdotes, dialogues, jokes, and reminiscences. They dealt with vaudeville, Boston, the Middle West, and Press agents, and there was one entitled Buy It, Put It Away, and Forget About It. It appeared in May 1929, and began like this: I come from common stock. I always planned to begin my autobiography with this terse statement. Now that introduction is out. Common stock made a bum out of me.

This is the way the autobiography of Julius H. Marx actually begins: The trouble with writing a book about yourself is that you cant fool around. If you write about someone else, you can stretch the truth from here to Finland. If you write about yourself, the slightest deviation makes you realize instantly that there may be honor among thieves, but you are just a dirty liar. Julius often cuffs himself about like that, and he takes Groucho in his stride. You learn about the comedian almost incidentally, for the book turns its brightest spotlight on the humorist, wit, essayist, philosopher, and man of many worlds.

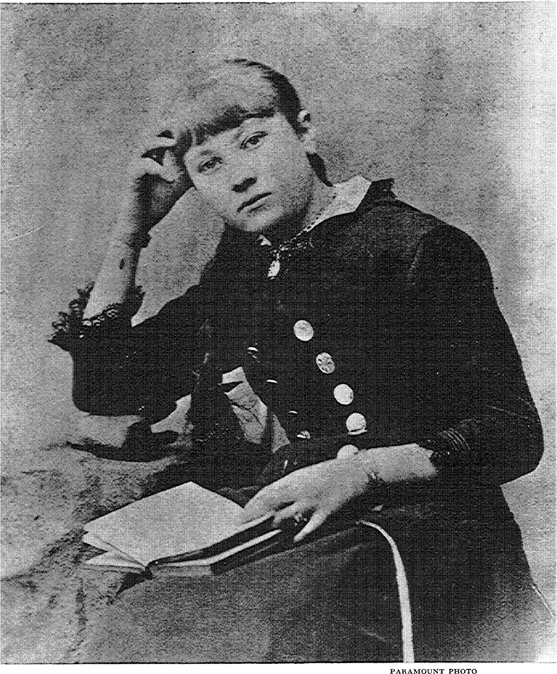

The twenty-eight chapters are, in part, the saga of the five sons of a Yorkville tailor and his wife, and of how they came out of the Nowhere into the Here, out of the small time into the big time, out of a dark obscurity into a luminous fame. Well, there was one spark of immortality in the family to begin with. A maternal uncle of the Marx boys was Mr. Shean, who rode to undying fame in the company of Mr. Gallagher.

In the song Fine and Dandy there is a line that goes: Even trouble has its funny side, but Groucho, as I shall call him from now on, shows not only the funny side of trouble, but also the troublesome side of fun. Before the Marx Brothers became an everlasting part of our great co-medic history and tradition, they ran the hard gamut of everything. The purely autobiographical chapters, in the swift, expert, and uniquely witty style of the master, tell how the young MarxesChico, the eldest, was the only one to graduate from grammar schoolsurvived the abuses, loneliness, crookedness, and cruelty of small-time vaudeville without becoming disenchanted by show business, although they had to fight for a livelihood, learned to carry blackjacks and to hold their own with the monsters called theatre managers. The only hospitality they enjoyed in the awful early years on the road was supplied by sporting houses and pool rooms, for the actor was suspect, not glamorous, in those days.

Grouchos book might have been subtitled: How I Ran an Allowance of Five Cents a Week into an Income of $18,000 a Week, with a Vicuna Coat and Two Cadillacs Thrown in. Money plays a big part in this, as in any other American success story, and in a chapter called How I Starred in the Follies of 1929 he tells how he lost nearly a quarter of a million in the stock market crash. (That May 1929 New Yorker piece of his was indeed prophetic.)

The stock market did not make bums out of the Marxes. It was a kind of godsend, for in 1931 they went to Hollywood where their guardian angel introduced them to Irving Thalberg, the man responsible for the screening of A Day at the Races, and that finest of all Marx masterpieces, A Night at the Opera. The book gleams and glitters with the names of show business and show art. George Kaufman is praised for his valuable contribution to the Marx success, and we meet, or rather Groucho met, Charlie Chaplin when the Little Man was making only fifty bucks a week in an act called A Night at the Club.

Everything in this book is fresh and new, for neither Julius nor Groucho included any of his earlier writings. Those two share a cold eye, a warm heart, and a quick perception. Groucho and Me is an important contribution to the history of show business and to the saga of American comedy and comedians, comics and comicality.

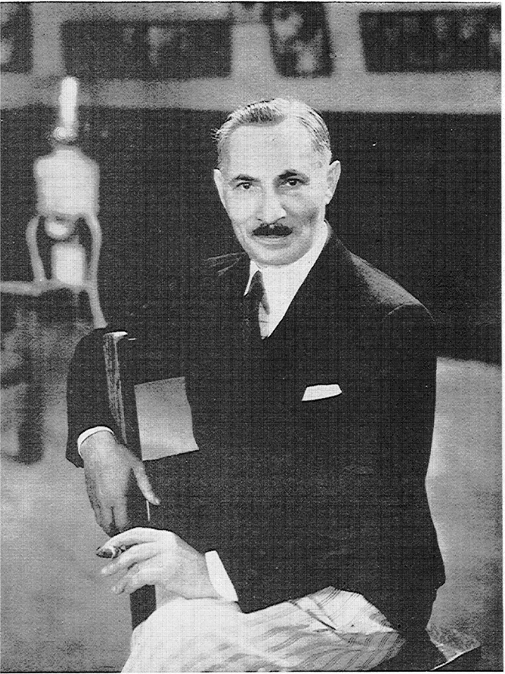

James Thurber