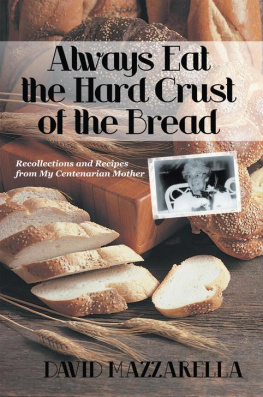

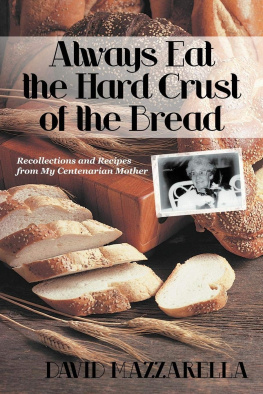

Always Eat the Hard Crust of the Bread

Recollections and Recipes from

My Centenarian Mother

David Mazzarella

iUniverse, Inc.

Bloomington

In association with TPD Publishing LLC

Always Eat the Hard Crust of the Bread

Recollections and Recipes from My Centenarian Mother

Copyright 2012 by David Mazzarella

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

iUniverse books may be ordered through booksellers or by contacting:

iUniverse

1663 Liberty Drive

Bloomington, IN 47403

www.iuniverse.com

1-800-Authors (1-800-288-4677)

Because of the dynamic nature of the Internet, any web addresses or links contained in this book may have changed since publication and may no longer be valid. The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them.

ISBN: 978-1-4759-1394-1 (sc)

ISBN: 978-1-4759-1395-8 (hc)

ISBN: 978-1-4759-1396-5 (e)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012906717

iUniverse rev. date: 6/25/2012

Contents

Dedication

For my inspirer and wife Christine, and all those in whose veins Benignas blood flows.

B enigna Preziosi Mazzarella, my mother, wasnt much given to profound sayings. Sometimes shed parcel one out as a sort of soundbite. Her favorite was probably Other people are not like us, referring to what she saw as the familys hallmarksa certain stoicism, a tendency toward accommodation, a slowness to anger. She said it with both pride and resignation. Other people could be selfish, lacking in good manners, but not us. She might say this after some perceived betrayal or a merchants sleight of hand.

I kept coming back to that maxim as I contemplated the astonishing amount of time my mother spent on this earthone hundred and seven years and nine months. I didnt think of the phrase only in the same way she did, in regard to the family; I also thought of it in regard to her .

Other people were not like her . Other people, at least a lot of them, ate and drank in a way that gave them big bellies and sugary blood. She ate simply all her life; fatty food was an enemy. Other people dreamed fitfully of retirement at sixty-five or earlier. She worked in a factory until she was eighty, and wished she could have gone on for years more. She lived her way, somehow following much of the advice in those self-improvement books she never read, and never would have dreamed of reading.

And yet, as I tried to explore the reasons for her longevity, it occurred to me that her life seemed exceedingly mundane. She was a child of the twentieth century, all of it, having been born in 1900 in southern Italy. (She died in 2008.) Childhood was spent at the apron of her mother, a strong-willed widow. Barely out of her teens, the pretty Benigna joined the flood of what must have been an anxious emigration to a strange land, the United States. She married a paisano, a home townsman, for whom she had had little time in the old country, but with whom she became reacquainted once he had emigrated too. They raised three children, first in the teeming city of Newark, New Jersey, and then in one of that citys all-American suburbs, South Orange. Outwardly, it was a life familiar to millions, of home and hearth, decades of work, a little upward mobility, some friends and relatives, and occasional plain pleasures, followed finally by tranquil old age and death.

Seen this way, her life seemed the epitome of ordinariness, except that it also embodied a perfect combination for longevity: amazing genes, adherence to the famous Mediterranean diet, and almost compulsive physical activity (mostly in the form of walking, fast). The genes were a gift; the Mediterranean diet was adapted to her tastes (Down with garlic! Her eating habits are on display in the cookbook chapters that follow.); and the exercise was a hallmark of her personality.

She imbued her days with an energy all her own, flowing determinedly from one phase of her life to the next, always the center of attraction despite never having lobbied for the honor. Her personality was complex; her enormous empathy made her an ideal confidante. She had an uncanny way of sensing the feelings of others, so it wasnt possible to keep any subsurface troubles from her for long. Neither was it easy for her to keep her own concerns hidden; with lips tight and mouth turned downward, she would signal that something was bothering her. There were times she would let it all out too, even with salty words that momentarily challenged the familys vaunted reputation for stoicism. This pointed to a central contradiction of Mamas. She could be demure and submissive, or forceful and steely. One mood was an overlay of the other, depending on the circumstance.

It was not all smooth sailing. As did millions of families, hers struggled through the Depression, emerging whole and healthy. In midlife and beyond, she had to worry about and care for a few needy relatives, including her funny, slightly eccentric, hypochondriacal husband, who thought of her as a cat because of her looks and movements. For these relatives, all of her generation, she was a nurturer, though at times a reluctant one. For her children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and others in an expanding circle, she was a happy nurturer. Could that attribute have led to a long life?

As to how Mama saw herself, that was lacking in complication. She just plowed ahead, one day after the other. She seemed to have no regard for her age. It were as if, at ninety-five, she thought of herself as sixty, or fifty, or forty. Only in her last years did she seem to turn more philosophical: Ah, she would sigh, we all have to die sometime. But you got the idea she didnt believe that either. Curiously, this attitude was infectious, in the sense that the rest of us also believed she could and would go on forever. Or, at least, we couldnt envision the day she would leave us. Even when she passed the age of one hundred, news that she was sick with something or other was dismissed. She would recover. Invariably, she did. And while nonchalant about her clocking off of the years, we knew we would never match them, and probably wouldnt come close.

What might Mamas life tell us about longevity, aside from the presence of good genes, which many people have but still dont reach her years? Maybe only that moderation has a role. And regularity of habits. And a disciplined palate. And a stiff spine. And pleasure found in work. And laughter. And a carrying of ones years lightly. And love and protection of familyeven some of its more nettlesome characters.

In these pages is a buffet of facts, stories, personal foibles, sayings, and recipes that may serve to flesh out those attributes.

Food, Genes, Energy, and Some Crosses

Foremost among Mamas special traits was her mastery in the kitchen, though she hardly would have called it that. A cautious eater herself, she had a knack for turning out dish after dish that found favor among family, friends, and even tradesmen, whom she often rewarded with treats as they worked around the house.

There is no single fountain-of-youth discovery in the search for links between Mamas longevity and her eating habits. She didnt know anything about special diets and health-food fads. But there were certain tastes and practices of hers that were healthful by any standard, and, I believe, helped her reach to within three months of her one-hundred-and-eighth birthday before she died of pneumonia on January 20, 2008. And the food she cooked tasted good, very good, to four generations of the family. I describe in this book some dishes that I think a general audience might find original.

Next page