To all of the mothers who dutifully slaved overthe hot stove for us, when they would rather havebeen doing something else. And especially to mymother, who would rather have gone bowling.

Copyright 2016 by Rob Chirico

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in wholeor in part in any form. Charlesbridge and colophon are registeredtrademarks of Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc.

An Imagine Book

Published by Charlesbridge

85 Main Street

Watertown, MA 02472

(617) 926-0329

www.charlesbridge.com

This book was designed and produced by

Bunker Hill Studio Books LLC

285 River Road, Piermont, NH 03779 (603) 272-9221

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file

Names: Chirico, Rob, author.

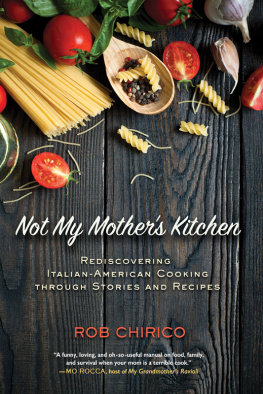

Title: Not my mother's kitchen : rediscovering Italian-American

cooking through stories and recipes

/ Rob Chirico ; with illustrations by the author.

Description: Watertown, MA : Charlesbridge, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2015037553|

ISBN 9781623545017 (reinforced for library use)

| ISBN 9781632892003 (ebook)|

ISBN 9781632892010 (ebook pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Cooking, Italian. | LCGFT: Cookbooks.

Classification: LCC TX723 .C535 2015 | DDC 641.5945dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015037553

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

My thought was you dont let traditionbind you. You let it set you free.

MASSIMO BOTTURA (Italian restaurateur and chef)

Introduction

Thats Italian!... Not!

My mother was an assassin.

This is a bold confession for a son to make, but its true. My mother wasan assassinin the kitchen that is. Now please dont take this amiss. Outsideof the kitchen she was one of the kindest, sweetest, and gentlest ofpeople you could ever meet. As the writer Bill Bryson noted about his ownmother, When she dies she will go straight to heaven, but no one is goingto say, Oh, thank goodness youre here. Can you fix us something to eat?I credit my love of books to my parents. Then there was music. Our homewas filled with musicBroadway, jazz, Sinatra (of course), and even someopera. After all, we were Italian. But that was outside the kitchen. In frontof the stove or at the microwave, my mother was the culinary equivalentof John Wilkes Booth. It has been alleged that Booth killed our countrywhen he shot President Lincoln. My mother did the same to Italy. MartinScorsese said, If your mother cooks Italian food, why should you go to arestaurant? Clearly, my mother never cooked for him.

Growing up, my conception of Italian food didnt differ much fromthat shared by most Americans. It was the food you were served in Italianrestaurants: antipasto with olives and provolone, spaghetti and meatballs,veal Parmigiano, and lasagne with plenty of oozing mozzarella cheese. And yet, even before I ever stepped foot into a ristorante in Italy, the very wordrestaurant made me think of Italian food. That word evoked in me thepleasurable sensation I felt as I opened the doors and breathed in the aromasissuing from the restaurant kitchen. My sense of smell was so acute that myfather once said that I had a 20-20 sniffer. Mind you, this was not a compliment,as his remark was in reference to my clipping a clothespin to my noseto block out the odor of our Friday fish cakes. At the time, though, the morepleasant aromas beckoned me to eat, not to cook.

So how does a boy go from growing up in a home where real food and adevotion to cooking were nonexistent to becoming someone who devotesconsiderable time every day to ruminating over the preparation and executionof every dish? I sometimes look back and wonder if my passion for goodfood was born out of self-defense: a defense against malformed, nearly crematedhamburgers; frozen and canned vegetables overcooked to the pointthat you could practically use a straw to ingest them; and, of course, so-calledItalian food that was about as authentic as UFOs and Elvis sightings. But Cacioe Pepe () were a long way off.

Self-defense or not, even as a picky little kidwho hadnt the faintestidea that he would one day be editing cookbooks, become the winner in anational cooking competition, or spend nearly a decade working in a restaurantI must have had an inkling that there was more to Italian cuisine thandumping Chef Boyardee Spaghetti and Meatballs into a pot. When I didbegin to realize that there was more, I wanted to cook. It should have beensimple. So many people did it. What I discovered over time was that therewas much, much more to it than I had imagined. Im sure Im not alone inthinking that all I wanted to do was go into the kitchen and cook. Why didthat prove so very difficult?

Back in the early 1960s, our neighborhood of Jamaica, Queens, was a mixof Italian, Polish, Irish, and Greek families. On any given summer Saturdayafternoon you could hear Sinatra, polkas, the Clancy Brothers, and bouzoukimusic streaming from different houses. By evening time, the aromasof home cooking began to fill the air. Mrs. Giorsos baked incredible buttercookieswhich made up for the stench that filled the neighborhood when she was making her own lye soap. Mr. Berezowski had a special cache ofhorseradish that could singe your eyebrows if you just sniffed it. I loved it,and have since grown back a full pair of eyebrows.

But the best aromas poured from the kitchens of my Italian friends. Thesmells of bread baking and sauce cooking permanently bathed my cousinGerards home. It was particularly a treat when his grandmother (my greataunt)visited. Early in the morning she planted herself in the kitchen andspent the whole day rolling out dough and hand cutting pasta noodles. Orshe would spend the day cutting up chickens for stew and chopping vegetablesfor her minestrone. (Had I only known at the time, I would have toldher that her soup would be even better if she added a large piece of Parmigianocheese rind.) Her spicy meatballs and tomato sauce came from recipeshanded down from her mother, and, in turn, she passed the family recipeson to her daughter, my aunt Josephine. Nanny most assuredly had manyof these same recipes, but my mother claimed that she never learned thembecause they were Nannys secrets.

In truth, I suspect that my mother was never interested in learning thosesecrets, let alone cooking the recipes. Most of my Italian friends seemedto have had families that tried to preserve at least a part of their culinaryheritage, but the Italian food that we ate at homesave for the spaghettiand tomato saucecame from the freezer or the closet: Celentano frozenmanicotti, 4C canned Parmesan, Italian Hamburger Helper, and NoodleRoni. Occasionally there was the extra-hearty meal when she neglected toremove the plastic from the manicotti, which gave the cheese an entirelynew dimension.

Such prepared foods were convenient for someone like my mother whoclearly found cooking to be drudgery. Meanwhile, our neighborhood Germandelicatessen provided us with rare roast beef, potato salad, coleslaw, and otherfoods made daily in the back kitchen. That same deli on Parsons Boulevardand I now apply the term deli looselyhas changed hands many times,and you can be sure that the roast beef today comes in a Cryovac sealed bagwhile the potato salad and slaw come in ten-pound buckets. With plenty ofoptions to spare her from cooking, my mother was free to pursue activities she found much more satisfying.She sold Avon products. She likedto bowl, and her trophies provedthat she was good at it. She playedmahjong with her friends. Shewas also something of a windowlady, one of those women whoenjoy spending hours sitting bythe window, just watching theworld go by.

Next page