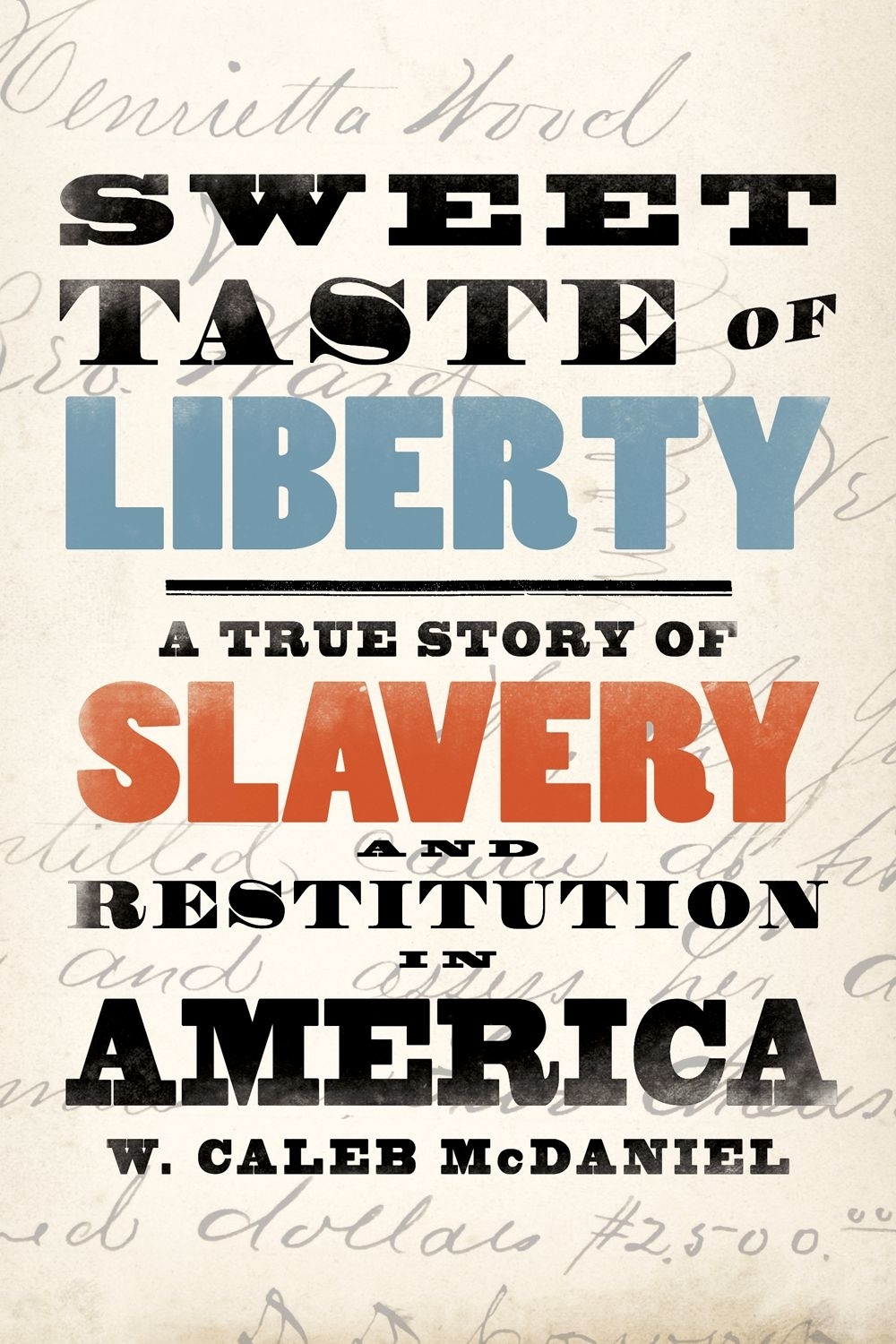

Zebulon Ward of Arkansas liked to say that he was the last American ever to pay for a slave.

It would have been a doubtful honor even if it were true, as one newspaper said about Ward in 1887. Wards story, however, was dubious itself, and the true story brought him no honor at all. Eight years before the Civil War began, he had kidnapped a free woman and sold her as a slave. After the war, she had sued him for an enormous amount of money, arguing that she deserved reparations for her enslavement. But Ward preferred to tell his own version of the facts, making himself out to be The Last Slave Buyer. Many who heard his story would never learn the truth.

Tall and broad-shouldered, with a cropped, gray beard, Ward was well known by the 1880s as a man with a knack for spinning yarns, perhaps the most unique raconteur south of the Mason and Dixon. Some said he looked like Ulysses S. Grant and had even impersonated the ex-president at a party both men attended. True or not, that was the kind of story he loved to tell, and Wards stories often made their way into the press. Portions of his history are like a romance, wrote one reporter in 1888.

By then Ward was one of the richest men in the South, having made his fortune leasing state prisons in the region. He claimed to have served in two wars, and some called him Colonel. He may have been most famous, though, as a horseracing enthusiast, a man of the turf. Before settling in Arkansas, Zeb Ward had raised Thoroughbreds in his native state, Kentucky, and at one race held in 1863, his horse had been the only one to hear the starters signal: the filly won while the other horses stayed at the starting line. Delighted by his luck, Zeb had pocketed the stakesalong with another anecdote for his repertoire.

He found a perfect stage for his stories in 1887, during a long stay at New Yorks St. James Hotel. Located on Broadway and Twenty-sixth Street, the hotel had a popular bar for actors, socialites, and turfmen such as E. Berry Wall, the dandyish King of the Dudes who claimed to have introduced the cocktail and the tuxedo to Americans. As a raconteur himself, Ward felt right at home, and reporters found him at the hotel in a reminiscent mood. Most evenings, admirers crowded around to hear his stories, told with an old-school eloquence that drew listeners in. And no story impressed them more than the one about how he allegedly became the last man in this country to pay for a negro slave.

The story was brief, according to Ward, and it had the feel of an anecdote he must have told before. This time, though, a reporter in the audience wrote it down.

Colonel Zeb Ward, of Little Rock, Ark., who has been warden of three state penitentiaries, declares that he was the last man to pay for a negro slave in this country, and that was the result of a suit brought against him a few years ago by a woman slave whom he wished to set free, but who remained with him during a long dispute in the courts regarding her ownership. She sued for remuneration for six years service after the emancipation act, and gained a verdict. Colonel Ward says that in making out the draft for the amount found he worded it: To pay for the last negro that will ever be paid for in this country.

That account soon traveled far beyond New York. Within days, it had been reprinted in cities across the country: Cleveland, Chicago, New Orleans, San Francisco. Then the story kept spreading, even though it was mostly false.

At least one person could have corrected the record, however: the woman who remained nameless in Wards popular account. Unbeknownst to him, she was living in Chicago in 1887, along with a son who had just begun attending law school there. And had anyone told her what Ward said in New York, she would have told them a very different story.

Her name was Henrietta Wood. Her story began in Kentucky. She was born there, enslaved by a man named Tousey, and then sold twice in her youth before being taken to New Orleans. Eventually, she was brought north to Cincinnati, Ohio, where Woods mistress at the time declared that she was free. That happened in April of 1848. But in 1853, as she was settling into freedom, Wood was kidnapped in a carriage, taken back to Kentucky, and reenslaved by a strangerZebulon Ward.

Ward sold Wood to a slave trader who took her to Mississippi, and a cotton planter who bought her there later moved her to Texasfacts that Ward did not mention in his story at the St. James. Far from wishing to free her, he had captured and sold a woman who was already free. He thereby doomed her not to six years service, as his version had it, but to more than a decade of reenslavement in the Deep South. As a result, Woods son would be born into slavery, too, in 1856. Neither of them would be freed until after the Civil War.