The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

By the study of their biographies, we receive each man as a guest into our minds, and we seem to understand their character as the result of a personal acquaintance, because we have obtained from their acts the best and most important means of forming an opinion about them. What greater pleasure couldst thou gain than this? What more valuable for the elevation of our own character?

East London, Wednesday 22 March 2006, 11 a.m.

I knock on the front door. The docklands home of Ian McKellen is in a terrace, on a road with double yellow lines either side, and through which hardly more than one car can pass at a time. The blue door opens as if by itself onto a view of books on shelves. No sight of McK.

Come in! Ill be with you in a moment, a familiar voice calls out. At a glance the house is narrow, with a long room running its length to a full-width window with a step or two up to a riverside balcony and a bust of Shakespeare. It is on five floors, a lower floor, a ground floor and bedroom storeys. Elegant with stripped wood, the aura is Victorian. It resembles a cabin; reverse the house through ninety degrees, and I can well imagine it as the below-deck of a royal river-boat: like Cleopatras barge, the burnished throne which burns on the water.

Theres a clump, clump, clump behind me from heavy shoes descending a wooden staircase.

We hug. We are like family, friends from Cambridge, but havent seen each other for a few years. I have written to him to request an interview. Although I have known McKellen since 1958, I am here for the first time on a mission, that of would-be chronicler or interviewer.

A moment of uncertainty. My eyes move to the window. The image I have is hardly that of a sweet Thames that runs softly while I end my song, for theres a sight of dark water. I think of the strong brown god sullen, untamed and intractable T. S. Eliots Thames. The vibes are of Shakespeare and Eliot, not inappropriately given McKellens lifelong love affair with W.S.

I know, McKellen says, as if picking up my sense of the view. On this cold grey March day this is something of an anticlimax. Gulls wheel in the air above. Downriver on one side is Greenwich, while on the other we just get a glimpse of Tower Bridge. We speak briefly of the sheer expanse of water and the industrial landscape on the opposite bank.

As if to grace the river with beauty he has since acquired an Antony Gormley sculpture of the human body similar to Gormleys Crosby Beach sculptures in Liverpool, which stands on the tidal beach below.

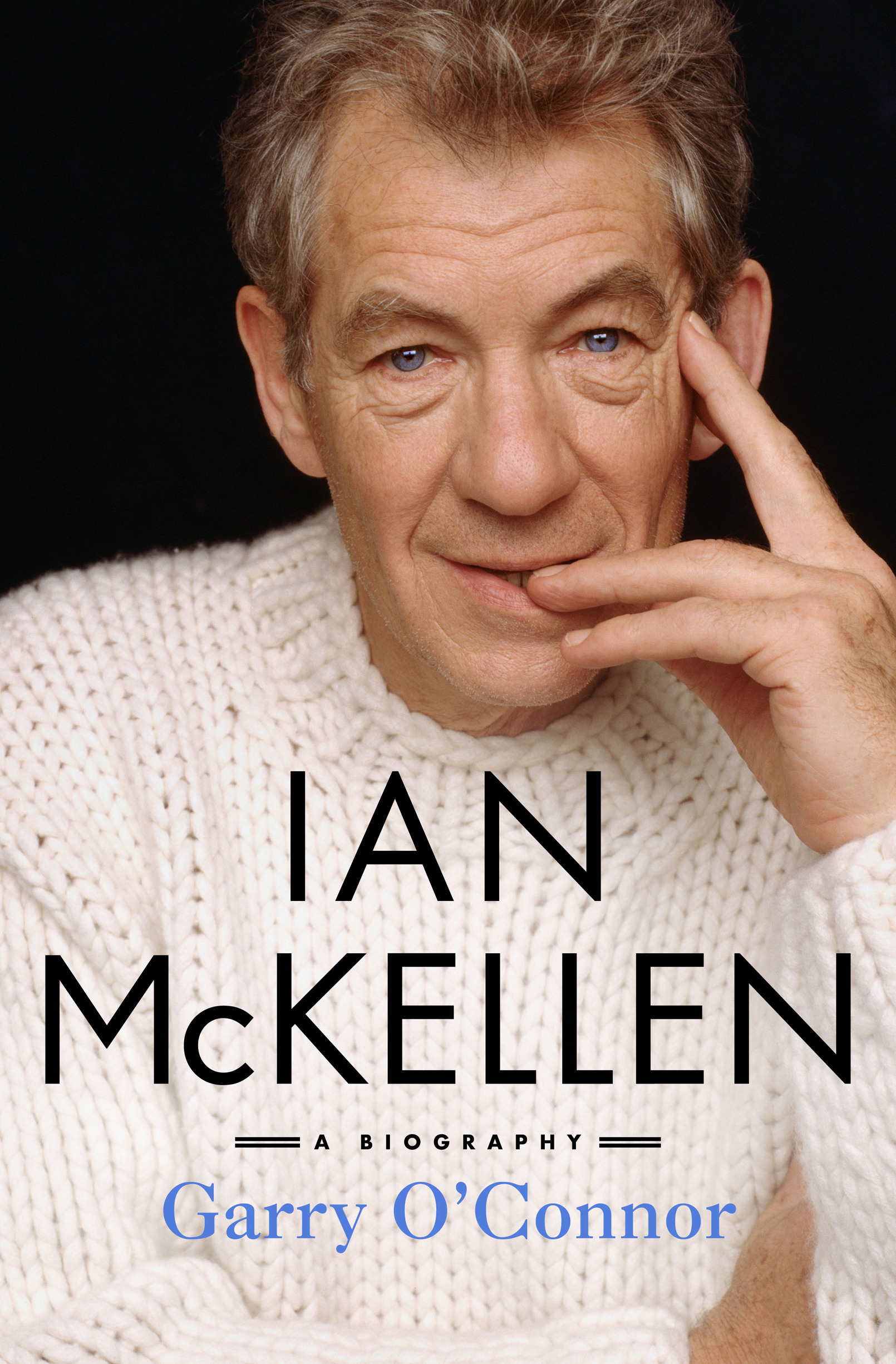

We are about the same height, five foot eleven, but he is more solidly built than me, so probably heavier, and strong in physique with a well-toned skin. He was very good-looking at Cambridge, where most of us never thought of him as gay, or didnt really think about it at all, but now his looks have a rugged authority, encrusting still a basic handsome and youthful presence. His shoes have iron heels. His jeans are well worn and have holes and glitter adorning them. He sports a heavy-studded metal belt, and an open-neck white shirt, which reveals his chest, a slight butch or Gothic feel to the image. He exudes an easy-going healthiness. Its a real power-dressing display, far from the duffel-coats of his younger self.

A dentists chair, a favourite personal effect, a friend tells me, has accompanied him from his previous home in Camberwell. I look around. A not very pleasant but brief thought flashes through my mind of Laurence Olivier playing the Nazi dentist Szell in Marathon Man with Dustin Hoffman as his victim. I dont ask.

Ill make coffee. How do you take it?

Black with a dash of cold milk. Thanks. He departs to the mauve kitchen where theres a black marble counter. I am by the balcony and climb the steps, looking over at the low-tide pebbles. He once found stranded there an animal corpse, hairless, waterlogged and bloated. He asked himself if it was a calf or a sheep or a goat or a dog. He stared at it until the tide came in. And for the next twenty-four hours he was off his food. He could not face meat after this and became vegetarian.

Still, this is not the time to bring up an unidentifiable, decomposing body on the beach. But with Ian there is always a degree of darkness as well as light. Uncomfortable is how a close friend has called him, but had they meant that he was uncomfortable in himself, or that this was how he made you feel?

We sit down to coffee. We would start with Cambridge. This was his first step on the ladder to professionalism. I am at once aware in him of a difference that I hadnt thought of before, a difference from so many of the leading lights there at the same time, among them Julian Pettifer, Clive Swift, David Rowe-Beddoe, John Drummond, Antony Arlidge, John Tusa, John Tydeman, to name but a few.

If I may start with a leading question. Why did you feel so different from most others who were up at Cambridge? I mention some of the names.

Yes, you are right. I suppose it was my age. I was nineteen. Just at that age one year made a big difference.

It was National Service. They were two years older. Drummond had been in the navy, learning Russian, John Tusa a Royal Artillery officer in Germany, Tydeman an Artillery officer in Malaya, Rowe-Beddoe a lieutenant in the navy, Tony Arlidge an RASC corporal in the Army Legal Service in Berkeley Square me a sergeant in Brighton in the Education Corps.

Theyd seen the world. I was away from home for the first time, with a foolish accent. Rowe-Beddoe and Tydey they were more mature, so much more mature Is this the characteristic self-put-down of the celebrity?

I look at the face, which is a narrative in itself. The eyes engage one with a quizzical and somewhat defensive look, but when I look back inquiringly, this is quickly replaced by a smile. The eyes are surrounded by wrinkles that change with and emphasise each mood. One feels there is an enormous well behind, filled with ages of memory and long, slow, steady thinking, but their surface is sparkling with the present, like the outer leaves of a vast tree. Who is this now? Which from the gallery of characters he has been? Not hard to guess. Gandalf.

A moment later there is shadow, a queer look comes into the eyes, a kind of wash, as if the deep wells are covered over. This for a moment could be Ian McKellen at twenty, playing Justice Shallow in Henry IV Part 2, when I acted in the same production for the Marlowe Society at the Arts Theatre, Cambridge. The blue eyes are the same, or nearly the same, at forty, fifty, in the various roles on stage or on film, and will be the same at eighty on stage or in the dressing room, on screen or off, recorded by private individuals by phone, camera, by the press Theres the piercing power stare of Magneto, the envious certainty of Iago spinning his lies to make Othello jealous