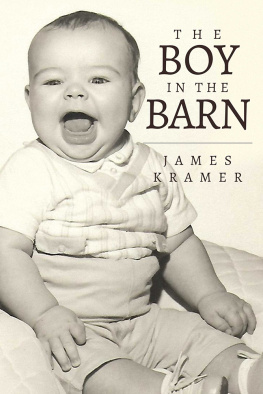

Leaving China

An Artist Paints His World War II Childhood

J AMES M C M ULLAN

ALGONQUIN 2014

For Kate,

You werent there then, but boy, have you been there for me ever since.

CONTENTS

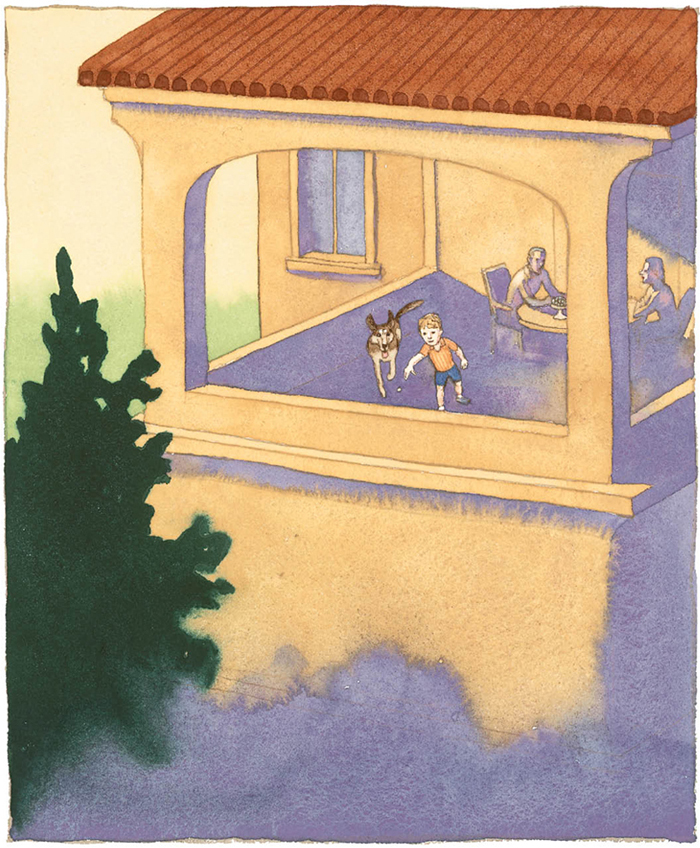

Throwing a Grape

M Y EARLIEST MEMORY IS OF THROWING A GRAPE. I was a two-year-old playing on the stucco porch of a neighbors house early one morning. I picked up a grape from a fruit bowl on the breakfast table and threw it for their German shepherd dog to chase. The grape bounced back off the wall and landed near me. The dog and I got to the grape at the same time, but I managed to close my chubby fingers around it just as the dogs jaws were about to claim the prize. The frustrated animal turned on me and bit me on the arm and on the back of the head. I remember in a dreamlike way the shouts and confusion of the adults when they called my parents and drove me to the hospital. It took fourteen stitches to close the gash on my head and six more for the wound on my arm. I dont remember the hospital or the pain, just the grape, the dog and the chaos. A little patch of hair never grew back on my head.

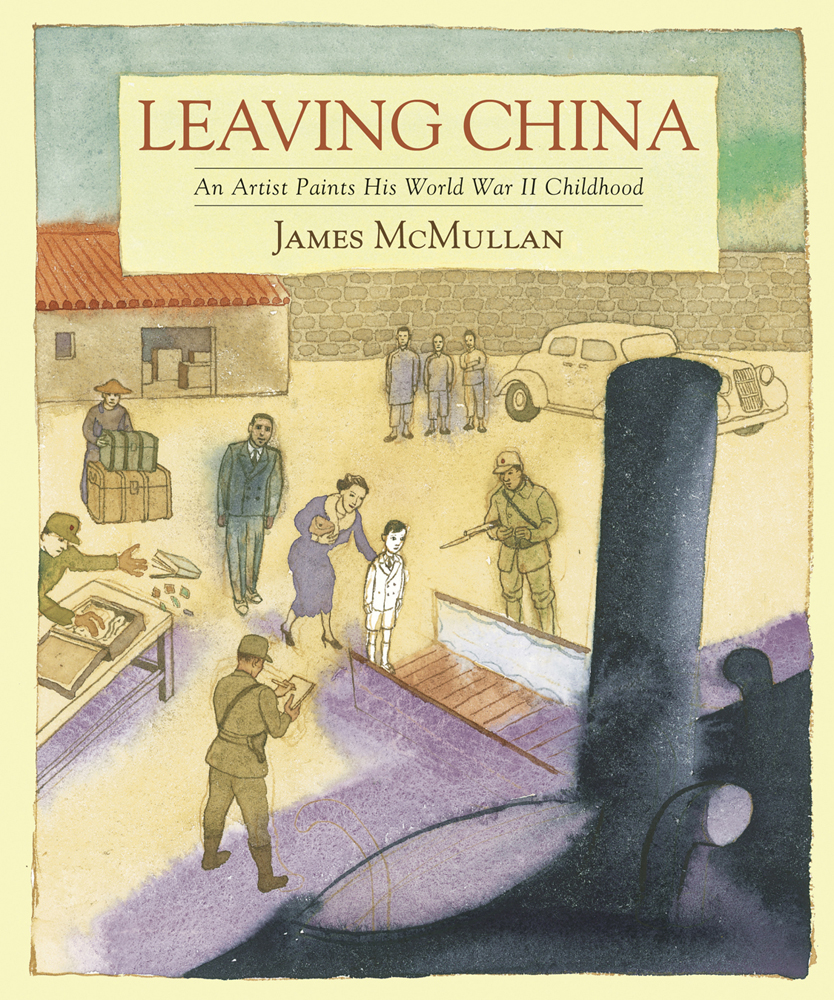

Looking back, I wonder if the dog attack had anything to do with the nervousness I exhibited during my childhood or whether I was simply destined to be a worried, anxious boy, German shepherd bites or not. I do know that my physical timidity in those early years was a concern to my father and mother and a great disappointment. This story of my peripatetic life during the Second World War, and of my familys beginnings in China, is also a story of that nervous boy gradually finding his strength in art and a way to be in the world that was not his fathers or mothers idea of a mans life.

The Two Houses

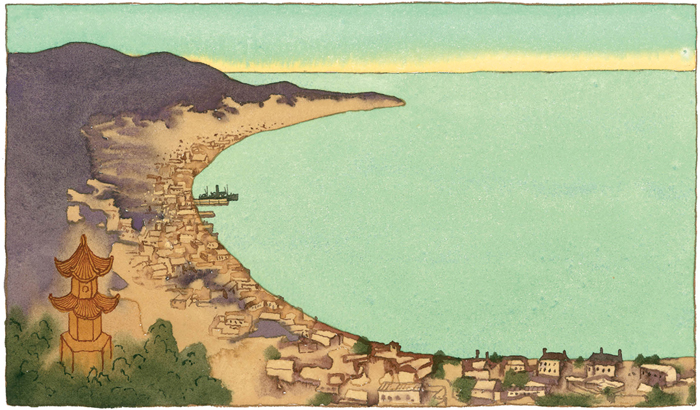

M Y FATHER MANAGED A BRANCH OF THE FAMILY BUSINESS in Tsingtao for the first three years of my life. Then we moved to Cheefoo, another port on the Shantung peninsula, where the James McMullan Company had its main office.

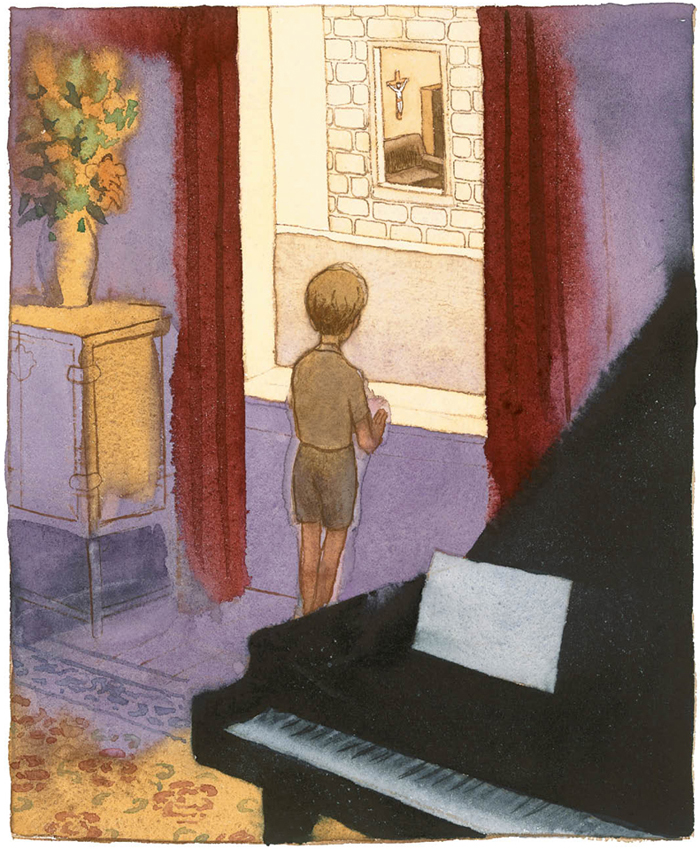

I remember certain things about the big stone house in Cheefoo. The carpets were rectangles of warm gray bordered by the particularly Chinese pink. Complicated rattan chairs with wide arms had indentations for holding drinks. At the corner of the room by a window was a big black piano and near it a fancy-looking radio made of different kinds of wood and a green eye that would get brighter or dimmer as my father fiddled with the knobs. There were lots of cigarettes in silver boxes and flowers on the tables. Music played from the record machine and often my father would sing.

I remember my aunt Gladyss house next door. It was also a big stone house, but it smelled different from ours, like old milk, and there was randomness in the way that everything was placed as though it had been dropped in haste wherever it was. There was also a crucifix on the living-room wall. It was an object that was missing from our living room.

As I was later to understand, the two houses illustrated in their different stylesours carefully put together for comfort and decorative effect, Gladyss ignored in order to concentrate on missionary tasksthe fact that the family history had created secular and religious branches.

The story of our family living a comfortable life in 1930s Cheefoo, China, had its beginnings in the bleak story of my grandparents, James and Lily McMullan, coming to China to work as missionaries.

James and Lily Arrive

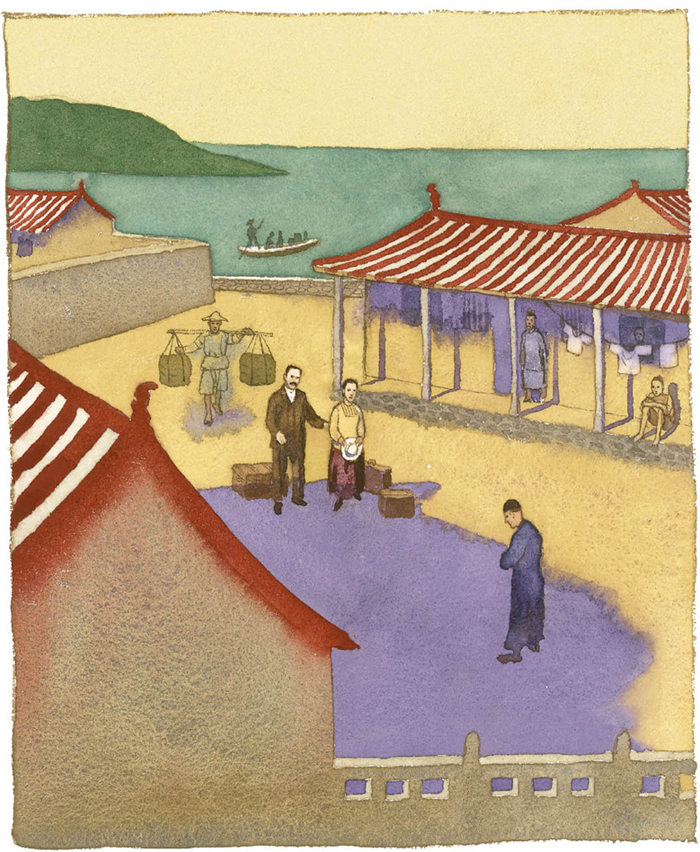

M Y GRANDPARENTS, JAMES AND LILY MCMULLAN, met as missionaries in Yangchow, China, in 1887. He had come from Ballycastle in Ireland and she from Bristol in England. They had both joined the China Inland Mission, known as the C.I.M., an interdenominational Protestant Christian group proselytizing the faith in many parts of China. They were married and started their careers in Chungking, but because James developed respiratory problems in the humid climate of that interior city, he and Lily were sent by the mission to work in the port city of Cheefoo, in northern China, where the air was drier and cooler.

What James and Lily encountered when they arrived in 1888 was a land suffering from a series of devastating floods. Crops had been ruined and many people had been reduced to a meager diet of a little rice, wild plants from the countryside, fish, when they could get it, and seaweed from the beaches. It didnt help matters that many people were caught in the crossfire of disputes between two warlords, and there was rampant piracy along the coast, as well.

Despite the presence of other missionaries, James and Lily were left to their own devices to find a way to evangelize among the Chinese. They set up a mission house next to a busy road, hoping to interest people in their preaching and in the Mandarin bibles that they were prepared to distribute. They were still learning Mandarin, but they would stand by the road with an interpreter, asking people to come inside the house to hear the words of the gospels. The area residents were focused on survival and the entreaties had few takers.

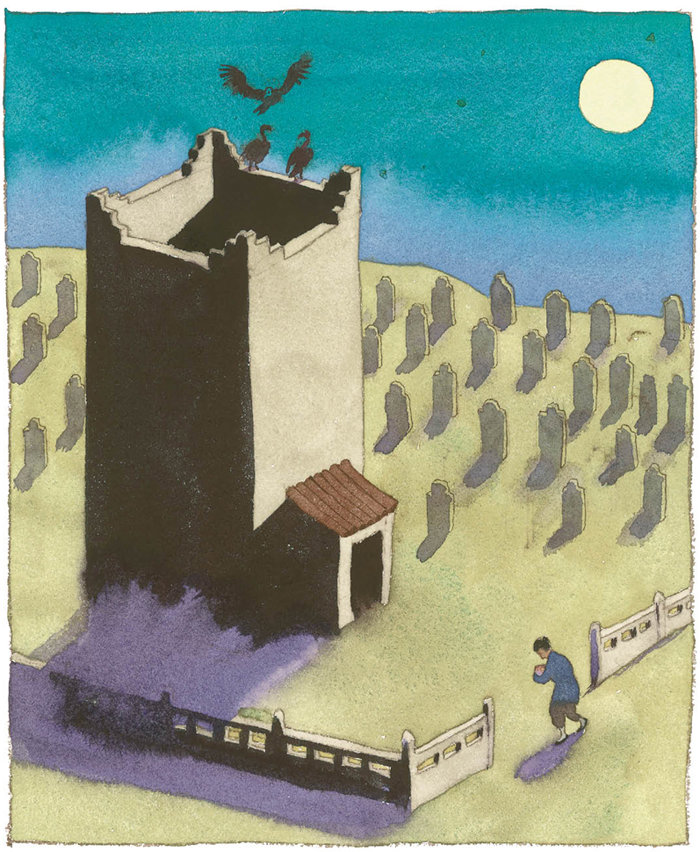

The Cemetery Tower

A S THE MONTHS PASSED, it became apparent to James and Lily that their work must focus on helping the people in Cheefoo with their immediate problems before they could persuade them to accept the Christian message. They began spending most of their time walking with their interpreter out into the neighborhoods to hear what was happening in the actual lives of the villagers. Among the stories of disease and difficulties in finding food or work, one other horrendous story gradually emerged. Families were so destitute, struggling to feed all their children, that some parents, when a girl was born, took the infant and left her to die in a tower that was part of the cemetery on the outskirts of town. Because the Chinese valued sons above everything else as a means of future support, they did not abandon infant boys in this way. The McMullans had been aware on a theoretical level that infanticide was practiced in China and was a historical aspect of the culture, but to see it happening in such proximity was a cruelty they couldnt ignore.

My mother first told me this central story in the McMullan missionary history when I was about five. I was horrified at the idea of these murders but secretly relieved to be a boy, who would not have been chosen for this awful ending.

Saving the Babies

J AMES AND LILY ARRANGED FOR A WATCHMAN at the cemetery to alert them whenever a baby was taken to the tower. When a message came, they would hurry to the cemetery and take the baby back to their mission house to feed her and keep her alive. At first, some of the babies died from lack of mothers milk, but soon Lily realized she could engage poor women from the town to act as surrogate mothers and breast-feed the little girls.