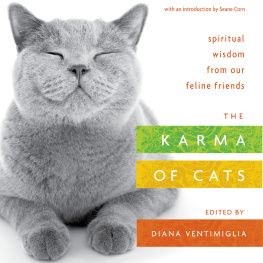

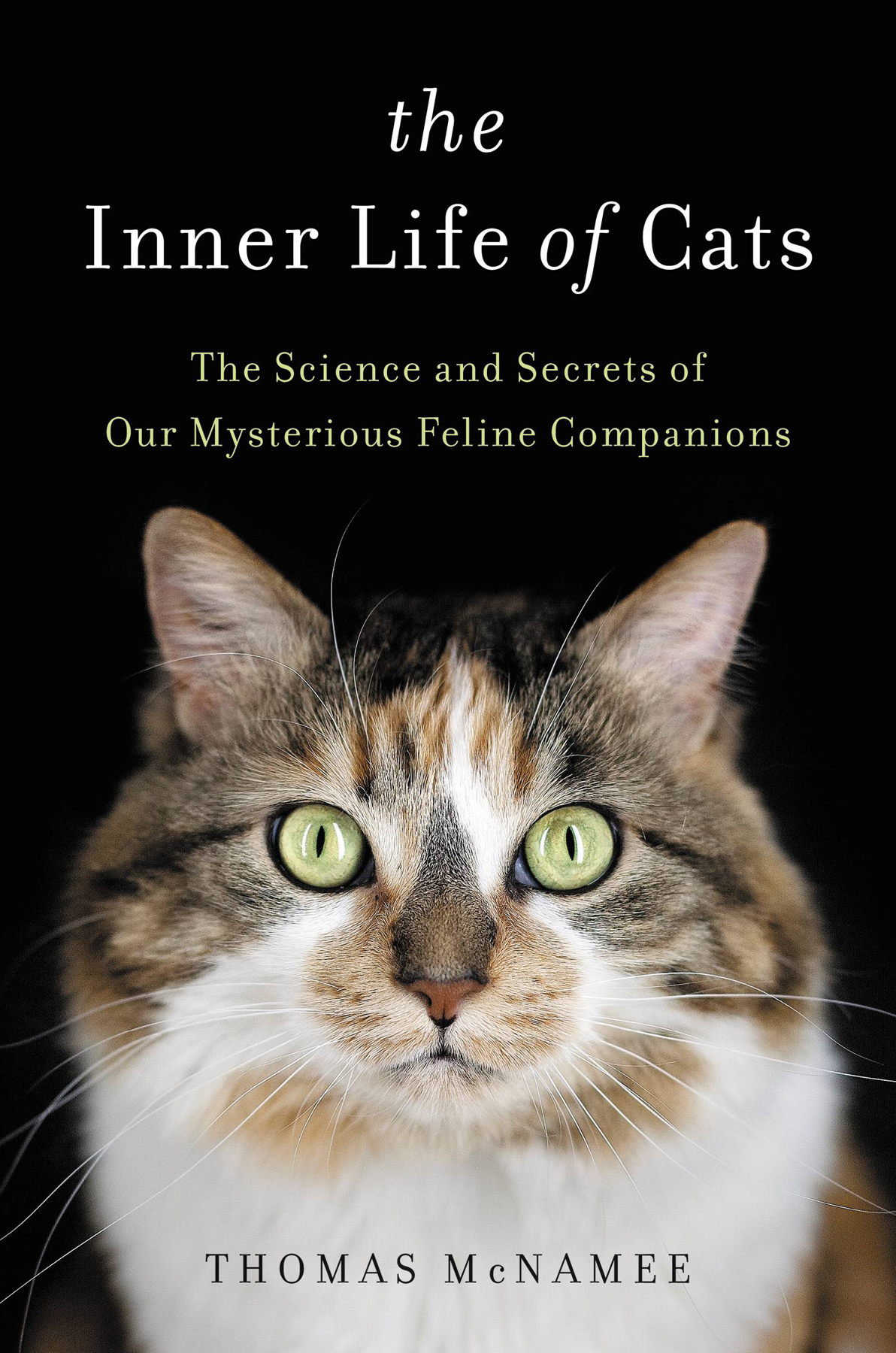

Augusta.

T he little black kitten had never felt snow. The snow was fresh-fallen powder, and a single pair of tire tracks led from the gate to the ranch buildings. She called for her mother. She tried to climb out of the tire track, but the snow crumbled beneath her paws and she fell back in. She could not walk very well, but she could walk, so she did, crying for her mother with every step. Night was falling.

She came to a building that smelled of food, and there were people inside, but there was also a dog barking. She continued along the tire track and came to a bridge. After a long moment of hesitation, feeling the deep booming of the water below, the kitten hurried forward, silent now. She followed the track to a wooden wall and could follow it no farther. She struggled along the wall through stiff grass and sharp-crusted snow, afraid, calling again for her mother. She found a little opening in the wall, just whisker-wide, and slipped through. The building smelled of strange things but was not so terribly cold.

She found a pile of rags, licked the snow from between her toes, and fell asleep.

The next morning, a still, cold morning, I saw a little black shape darting amid the unidentifiable junk in the equipment barn. A few clumsy minutes of chase and I had captured the kitten, who quieted as I held her with one hand and tucked her into the front of my jacket. She was shivering.

There was no answer when Elizabeth and I telephoned our only neighbor, an old Norwegian bachelor rancher, the only conceivable source for the miraculous appearance of this tiny furball. I went out looking for tracks, but there werent any leading from his place. Then I found the kittens footprints, smaller than a dime, still brightly visible in the snow all the way down our driveway from the county road, more than a quarter of a mile. There were tire tracks in the road showing that a vehicle had turned around. Someonewho? why? in the middle of the night, in a blizzardhad just dumped her there. What kind of person could do such a thing? We were twenty miles of icy dirt road from the nearest town, Livingston, Montana.

She gobbled the tuna and leftover chicken without looking up, and slurped the milk till her belly pooched out tight. It had a little white star at the center, matching the prim white bow tie at her sternum. She was otherwise all black. I cut down a wine box and filled it with spruce needles and leaf duff, and she used it right away, scratching busily to hide her deposit, watching us with wide eyes as we watched her back in proud delight.

We had no call to be so proud, for all cats naturally use litter boxes at first exposure as long as they feel calm and welcome, because the litter box sufficiently resembles the scent-marking spot that all their kind, including their wild ancestors, employ to proclaim, This is home.

We exiled her from the bedroom that night, but in the morning she greeted us at the refrigerator with her black stump of a tail straight up and vibratingthe universal cat gesture of greeting and confidence. Her evident understanding of indoor life and her readiness to be cradled in palm or elbow made clear that this was no barn cat, nor victim of abuse. The vet in town declared her female, healthy, about three months old, and likely to be on the energetic side. Her good cheer, he said, was probably partly due to having been tenderly handled as a baby and partly to an inborn sunny nature, a roll of the genetic dice.

Counting three months back made her birthday in August. We gave our gift from the god of chance the name Augusta.

Augustas first order of business on the ranch was to make a mental map of her new home. It was more than geographic. In the first days after her arrival, the snow kept her confined to the house, and she spent hour on hour tracing the contours of every chair, table, bookcase, telephone, carpet edge, window frame, and pencil holder. She also was also mapping things invisible to peoplemouse trails, bug spoor, hundreds of scents tracked in from outside.

All this was largely an exercise in olfactory memory. Only when each scent impression is recorded deep in the hippocampus is it coordinated with an image in the visual region of the cerebral cortex. That coordination is then deeply engrained. The power of your cats memory is evident when he startles at the slightest change in his customary surroundings. Cats have five times more surface area inside their noses than we do, and three times more receptor nerves per unit of area lining that surface. Of those receptors there are hundreds of typesthe possible combinations of scent perceptions, therefore, being nearly infinite.

A cats hearing is extremely acutethe widest range, in fact, of any mammal except bats. It is equally superior in its directionality: Watch your cats ears twitch and swivel, each moving independent of the other, as she tunes in on the precise place from which a sound is coming. For Augusta the faintest whisper of breeze on a screen, swirl of snow, or far call of raven was matter for instant, rapt attention. She seemed pure awareness.

During her explorations Augusta did not care to be interrupted. She knew her name very quickly, but she responded to it only selectively. If she was busy mapping, you could wait. She explored to the edge of exhaustion, barely managing to find a cushion or corner before sinking into dreamland. You could pick her up and haul her to bed unconscious like any other infant, all trust and contentment.

She would sleep for hours, limp as a rag doll, then suddenly be seized by a dream, moaning, teeth chattering, feet twitching, eyelids open to show not her eyes but the pink-pearlescent nictitating membranea sort of inner eyelid that distributes tears across the surface of a cats eyes, like a windshield wiper constantly clearing the eye of tiny debris as well as protecting it from infection or scratches. An adult cats eyes are as big as a human adults, and she can open the pupils three times as wide. A sort of crystalline mirror behind her retina, the tapetum lucidum, amplifies incoming light by as much as 40 percent. Thats what produces the familiar gold-green shine when a cat meets a flashlight beam in the dark.