Contents

For Alessandra

Plates

1. Portrait of Andrea Memmo by Mar. Caricchio, 1788 Tristano di Robilant

2. Portrait of Sebastiano Mocenigo (Alvises father) by A. Longhi Museo Correr, Venezia

3. An ivory miniature of Lucia and Paolina c.1775 Alvise Memmo

4. Portrait of Lucia Simon Houfe collection

5. Portrait of Paolina The Faringdon Collection Trust

6. Letter from Lucia to Alvise in response to his offer of marriage Andrea di Robilant

7. Palazzo San Marco Archivio Fotografico Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale Romano

8. Palazzo Mocenigo

9. The bronze horses of Saint Mark Museo Correr, Venezia

10. Anti-aircraft defence of Venice Museo Correr, Venezia

11. Statue of Napoleon by Angelo Pizzi, 18121814 Andrea di Robilant, courtesy of Mark Smith

12. Etching of Napoleon and Josphine

13. The Liberty Tree, Saint Marks Square, 1797 Museo Correr, Venezia

14. Alvisopoli Biblioteca comunale di Fossalta

15. Pencil drawing of Josphine by Jacques-Louis David Photo RMN Droits rservs

16. Portrait of Eugne de Beauharnais by Andrea Appiani Photo RMN Daniel Arnaudet / Jean Schormans

17. Josphines bedroom at Malmaison Photo RMN Grard Blot

18. Malmaison by Auguste Garneray Photo RMN Bulloz

19. Lord Byron at Palazzo Mocenigo Private Collection / The Stapleton Collection / The Bridgeman Art Library

Acknowledgements

The decisive impulse to write about Lucia came from Nancy Isenberg, Professor of Literature at Rome University; this book would not have seen the light without her persistent encouragement. A number of other friends offered their generous and sometimes crucial help along the way. Giulia Barberini, director of the Museo di Palazzo Venezia, shared with me her knowledge of the extraordinary palazzo where Lucia lived when her father was the Venetian ambassador in Rome. Wendy Roworth, professor of art history at the University of Rhode Island, helped me locate the long-lost portrait of Lucia by Angelica Kauffmann in Buckinghamshire. Benedetta Piccolomini proved a most enthusiastic guide during our exploration of what remains of Alvisopoli. In Austria, the kind and tenacious Clarisse Maylunas led me to Margarethen Am Moos during a rainy excursion in the countryside south of Vienna. My research took an entirely unexpected direction with the discovery of Lucias secret lover, Maximilian Plunketta discovery which would certainly have eluded me but for the steady prodding of Anne-Claude de Plunkett in Paris. A final tassel in the reconstruction of Lucias affair came from the ever generous Marco Leeflang in Utrecht. Iain Brown and his staff could not have been kinder in helping me with the Byron papers at the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh. And I am very grateful to Simon Houfe and Alvise Memmo for allowing me to reproduce Angelica Kauffmanns portrait of Lucia and the miniature of Lucia and Paolina as young girls.

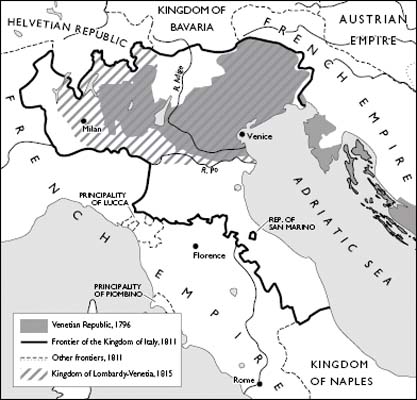

Maps

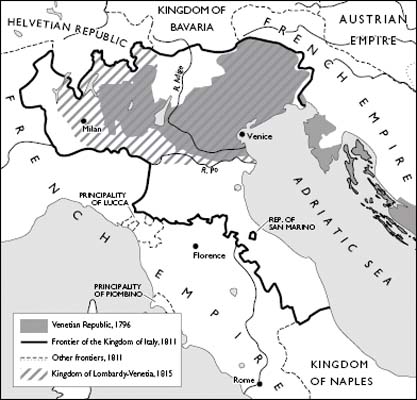

The Venetian Republic, which had developed over the course of a thousand years, came to an end with the Treaty of Campo Formio, signed on 17 October 1797 by the French and the Austrians. Venice passed under Austrian rule, but in 1805 it became part of the Kingdom of Italy, a pro-French puppet state. Austrian rule was re-established after Napoleons fall in 1814.

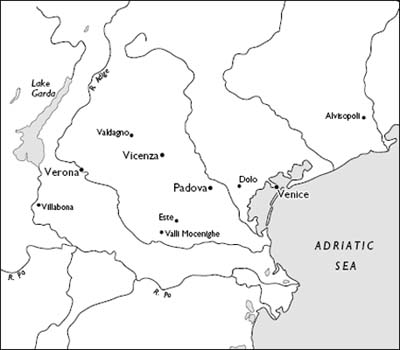

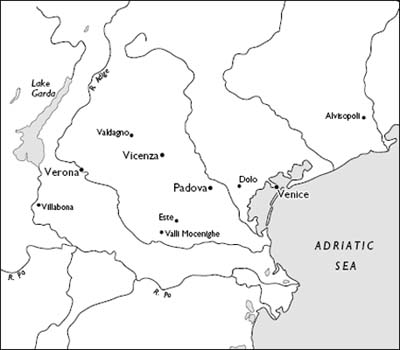

The families of Lucia and her husband were firmly rooted in the heartland of Venice and the Venetian terraferma. The key locations mentioned in the text are shown here.

Prologue

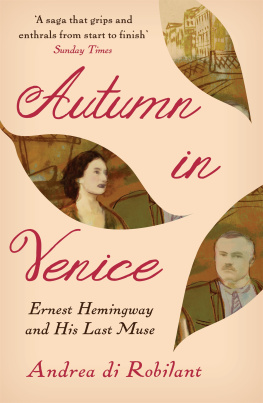

When I was growing up I sometimes heard my grandfather mention Lucia Mocenigo, my Venetian great-great-great-great-grandmother, who was known in the family as Lucietta. Her name usually came up in connection with Lord Byron, to whom she rented the piano nobile of her palazzo during his scandalous time in Venice. I learnt more about her many years later, while doing research on her father, Andrea Memmo, whose epic love story with the beautiful Giustiniana Wynne in the 1750s was the subject of my last book, A Venetian Affair. But it was not until a recent chance encounter brought me face to face with a ten-foot-high marble statue of Napoleon Bonaparte that my interest in Lucia deepened.

The statue, wedged into a corner, faces a damp wall in the androne of Palazzo Mocenigo, the venerable old palazzo on the Grand Canal which once belonged to my family. The emperor is clad in a Roman toga. His left arm is extended forward, as if he were pointing to a luminous future, though in fact he stares vacuously at the peeling wall in front of him. A mantle of dark grey soot has settled on to his shoulders, and a slab of roughly hewn marble links the raised arm to the head, giving the statue an unfinished look. It is hard to imagine a more incongruous presence than the one of a youthful Napoleon standing sentinel in that humid hallway to the sound of brackish water slapping and sloshing in the nearby canal.

Alvise Mocenigo, Lucias husband, commissioned the statue in the heyday of Napoleons Empire. It was intended to be the centrepiece of a vast utopian estate he built on the mainland. The statue, however, was not delivered until after the emperors downfall. By then Alvise was dead, and Lucia, not quite knowing what to do with such a cumbersome and politically embarrassing object, stored it in the entrance hall of Palazzo Mocenigo, exactly where it stands today.

The statue is all that remains of our family possessions in Venice. In the 1920s and 1930s, my profligate grandfather, having inherited the Mocenigo fortune, sold the palazzo and all its art treasures to finance his high-flying lifestyle. But he was never able to get rid of the marble Napoleon, which continued to languish in its corner untouched. Not long ago, while visiting Venice, I ran into the manager of Palazzo Mocenigo, which is now divided into apartments. Signor Degano looked at me as if I were a ghost from the past. It was quite understandable: not only do I carry the same name as my grandfather but the telephone line at Palazzo Mocenigo is still registered, strangely enough, under the name of Andrea di Robilant, even though my family has not lived there for more than fifty years.

After a few polite exchanges in the glaring sun of Campo Santo Stefano, Signor Degano reminded me that we were still the legal owners of the statue of Napoleon and asked me what we intended to do with it, adding that the various owners of the condominium would be quite happy to see it stay as it had been a part of the palazzo for so long. I said I would let him know and we parted. I stayed in Venice an extra couple of days to try to sort things out, though I realised there were few options, and none of them particularly appealing. The statue was officially notificata, which meant it could not leave the country, and would therefore be very difficult to sell. I couldnt take it home with me, of course, because I had no space for it. Besides, the thought of facing the grumbling owners of the

Next page

![Bosworth - Italian Venice: a history[Electronic book]](/uploads/posts/book/194557/thumbs/bosworth-italian-venice-a-history-electronic.jpg)