Table of Contents

To the generation, not yet born,

that creates a world where

plastic pollution is unthinkable

A NOTE TO THE READER

The format of this book is somewhat unconventional, not unlike the format of my life thus far. We have spliced together several stories. One is the story of my evolution as a citizen-scientist who learns how to shape a message and finds himself living it. Another thread can be considered a tell-all about plastics, the shape-shifting, inescapable material that seemed like a fun new friend at first but over time has shown its troubling true colors. I only wish we had noticed them sooner. Do not expect strict chronological order. Were dealing here with fragments, in space, place, and time, where boundaries between land and ocean are porous and barely seem to exist, and yet the dots do connect. This is also a love story, because I would not be doing any of what I do were it not for my deep and lifelong love of the ocean.

THE AUTHORS also wish briefly to illuminate the origin of their collaboration, which began on Hawaiis Big Island, in September 2008. The captain had decamped to an upcountry family property following a speaking engagement in Honolulu. Less than two miles away, at an orchid farm, Cassandra had launched Phase II of a USDA-funded investigation of recycled plastics as orchid growth media. Shed noticed in preliminary growth trials that plastics were not, as claimed, inert. Some types stunted, some enhanced growth, and some outright killed (synthetic carpeting). The local library was hosting a Zero Waste meeting. Charlie and Cassandra both showed upCharlie because he knew the Mainland consultants running it, Cassandra because she hoped to connect with recycled plastic sources. Charlie was curious about the growth trial and stopped by the nursery soon thereafter. Cassandra was reluctant to know more than shed observed firsthand about the unsettling properties of plastics, but she and her husband, Bob, couldnt help but listen raptly as Charlie described his work and findings. It was Bob who uttered the fateful words: This could be a book.

CHAPTER 1

A PLASTIC SOUP

THE OCEAN LOOKS like glossy blue cellophane, like a pond on a summer day. The sails are slack, and so are our hopes for a brisk trans-Pacific voyage. Were becalmed in the mid-Pacific high, and its not what anyone signed up for. Not Howard Hall, an old family friend, retired prep school dean and math teacher, and veteran deepwater sailor. Not the newlyweds, Howards son John and his bride, Lisa, who are making this voyage their honeymoon. Not me, captain of ORV (Oceanographic Research Vessel) Alguita, a fifty-foot Tasmanian-built catamaran, new enough that we still have a few things to learn about each other.

Nothing is riper with adventure than mapping a voyage, stocking the ship, casting off, pointing the bow toward the open ocean, checking the wind, and scrambling to set the sails. But our overriding concern at this moment, eight days out of port, is getting from point A, Honolulu, to point B, Santa Barbara, before running out of fuel and bonhomie. Weve deviated from the standard route due to exceptional conditions. What later turns out to be the most massive El Nio event on record is radiating through the North Pacific. Within a few weeks it will cause torrential rain and flooding in Chile. A marlin will be caught off the coast of Washington, having fled overheated Mexican waters. The trade winds seem to be holding their breath, compelling us to fire up Alguitas engines. It crosses my mind that The Rime of the Ancient Mariner starts at a wedding and winds up in the doldrums, like us, As idle as a painted ship / Upon a painted ocean.

Im an old salt myselftechnically, middle-agedbut this is my first crossing from Hawaii to California, though Ive sailed twice from California to the islands. Wed embarked on the standard route, which is to haul well north of Hawaii, then catch westerly trades that sweep you straight across to the California coast. Now the brisk winds that sped our way to the 35th parallel have died down to a whisper. Wed hoped to make it to the 40th before turning right and heading for the West Coast. I check daily weather faxes from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration and spot evidence of westerlies slightly south of where they would normally be. So we take a gamble and head southeast, into an atmospheric phenomenon called the North Pacific Highalso known as the doldrums, or the horse latitudes, where earlier mariners dumped livestock to lighten their ships and conserve drinking water. Its a more direct route to our destination, but a shortcut that could turn out to be long. The wind does pick up... for a few hours, but soon were back on diesel power. Howard and I agree its highly unlikely this calm will persist much longer. But if it does, we have a problem. And the problem is that we also need fuel for the ships electrical generator, which runs our onboard desalinization unit and charges batteries for our communication equipment. Were well stocked with food, but our only source of freshwater is the de-sal system. On the slim chance we get into big trouble, we need the ability to radio for help...

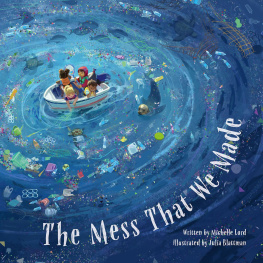

I begin to notice that this smooth painted ocean seems to behow best to put it?littered. Here and there, odd bits and flakes speckle the ocean surface. I believe they are mostly made of plastic. It seems odd and improbable. I do not note a first sighting in the ships log, so I dont know its exact day or hour. My best guess is August 8 or 9, 1997. Nor do I log sightings on successive days, or that Ive made a game of it. Days at sea are taken up by responses to changing conditions, dealing with equipment failures, and observing seafaring protocols. This means hourly entries in the ships log at the helm, visits to the engine rooms, and random trips to the galley for food or a nap in your bunk if youd pulled watch in the wee hours. My game is this: each time I come out on deck from the bridge, I make a bet with myself that this time I will not see another plastic scrap. But I always, always lose. No matter the time of day or how many times a day I look, its never more than a few minutes before I sight a plastic morsel bobbing by. A bottle here, a bottle cap there, scraps of plastic film, fragments of rope or fishing net, broken-down bits of former things.

This might have seemed normal, in a dismal way, if wed been sailing near my home port south of Los Angeles. But were halfway between Hawaii and California, a thousand miles from land, a place less likely to be littered than the moon, youd think. Every day for the next several days, as we motor across the eerily still waters of the mid-Pacific doldrums, they are always there: plastic shards, fluttering like lost moths in the surface waters of the deep, remote ocean. Im bothered, but Im also distracted by other matters.

Let it be said straight up that what we came upon was not a mountain of trash, an island of trash, a raft of trash, or a swirling vortex of trashall media-concocted embellishments of the truth. It would come to be known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a term thats had great utility but, again, suggests something other than whats out there. It was and is a thin plastic soup, a soup lightly seasoned with plastic flakes, bulked out here and there with dumplings: buoys, net clumps, floats, crates, and other macro debris. I was not a latter-day Columbus discovering a plastic continent. I was a seafarer who noticedat first incredulously, then with greater certaintythat this immense section of the northeastern Pacific Ocean, about halfway between Hawaii and the West Coast, was strewn throughout with buoyant plastic scraps.