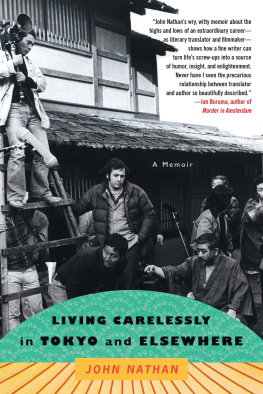

ALSO BY JOHN NATHAN

Japan Unbound

Sony: The Private Life

Mishima: A Biography

TRANSLATIONS

Rouse Up O Young Men of the New Age by Kenzabur e

Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness by Kenzabur e

A Personal Matter by Kenzabur e

The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea by Yukio Mishima

F REE P RESS

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright 2008 by John Nathan

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Free Press Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

This work is a memoir. It reflects the authors present recollections of his experiences over a period of years. Certain names and identifying characteristics have been changed.

FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nathan, John.

Living carelessly in Tokyo and elsewhere : a memoir / John

Nathan.

p. cm.

1. Nathan, John. 2. JapanologistsUnited StatesBiography.

3. AmericansJapanBiography. I. Title.

DS834.9.N36A3 2008

952.04092dc22

[B] 2007045502

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-9378-2

ISBN-10: 1-4165-9378-0

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

For my children,

Zachary, Jeremiah, Emily, and Tobias

Contents

One

If Music Be the Food of Love, Pray ( sic ) On

Two

Mayumi

Three

Yukio Mishima

Four

Kenzabur e

Five

The Theater of Tears

Six

Home Again

Seven

Summer Soldiers

Eight

Full Moon Lunch

Nine

Unraveling

Ten

A More Jewish Neighborhood

Eleven

Mercantile Years

Twelve

Stockholm

Thirteen

Familiar Roads

Fourteen

Detachment

An aged man is but a paltry thing

unless Soul clap its hands and sing

W. B. Y EATS

An aged man is but a paltry thing

unless Soul clap its hands and sing

W. B. Y EATS

PART 1

If Music Be the Food of Love, Pray ( sic ) On

I am asked Why Japan? with a bemusement that conveys an unspoken of all places! Perhaps my appearance and manner prompt the question. I am a hulking man with a hairy chest, parboiled hands, and a basso profundo voice in which I have a predilection for sounding my own horn. In short, there is nothing delicate about meallow me to say, nothing apparentyet delicacy is thought to be definitive of the Japanese sensibility. The truth is, my cultural wiring disposes me to appreciate Japan even less than people imagine. My roots are in New Yorks Lower East Side. My fathers father, Nathan Stupniker, was a reporter at The Jewish Daily Forward and a member of the Socialist coterie led by Forward editor Abraham Cahan that convened on Yom Kippur Eve to feed on pork in defiance of Adonai. Youll have to look around to find someone less likely to resonate with Japans grim earnestness than a disaffected Jew.

I was helped toward my career choice by uncertainty about my ability to vie on home ground. I arrived at Harvard from a frontier high school in the creosote desert surrounding Tucson, Arid-zone. Wemy younger sister, Nancy, and Ihad no business being there: our hypochondriac father contracted a chronic cold every New York City winter and decided, though he had never been west of the Hudson, to become a Sunbird. When I arrived at Harvard and walked into my suite in Matthews Hall South for the first time, I found on a round table a Fleet Street umbrella and a bottle of Danish mead. I considered uneasily that someone had left them there to remind me that I would have to do a lot of pretending to appear at home in Harvards slick halls. I followed the sound of laughter down the hall to an open door and walked in on a group of freshmen dressed in khaki pants and dress shirts with school ties loosely knotted around their necks. Andover boys, it turned out, who had read the Greek classics under the stern eye of Dudley Fitts; collectively they reminded me of the young T. S. Eliot as I imagined him at Harvard, polished and superior, remorseless in the presence of mediocrity. Two had entered Harvard with sophomore standing; another was among the handful of students chosen by Robert Lowell to take his poetry course. These classmates would be my closest friends throughout college, and though I was perhaps the most entertaining raconteur among them, I wasnt about to compete in English or philosophy.

When I was eleven, the first year of our rude transplanting from the Jewish comfort of New York to Tucson, I felt invisible to my schoolmates except as a butt of ridicule for being a know-it-all, and decided a pet monkey was what I needed to distinguish myself. I begged my parents to buy me one, but they declined to indulge me. Japanese was my pet monkey.

Not to say that anything exotic would have sufficed. There were many possibilities: Old Norse, Gaelic, Sanskrit studies. But I was genuinely intrigued by the Japanese language. At lunch in the Freshman Union, a student from Japan drew for me on a napkin a two-character compound and explained that it meant an infection that occurs beneath the nails of the toes or fingers (later I learned that the English word is whitlow). I stared at the abstract characters, astonished that they could signify so precisely. That week, I sat in on a class in modern Japanese literature taught by a voluble Italian American named Val Viglielmo. Viglielmo was a virtuoso: he claimed to be the only foreigner to have been psychoanalyzed in Japanese. He was lecturing on Ichiy Higuchi, a novelist who had written poignantly as a very young woman about life in the pleasure quarter in the late nineteenth century. As he introduced her he chalked on the board the characters for her name and the titles of her work with a swift, showy unerringness that inspired me with admiration and envy.

First-year Japanese language at Harvard in those days was taught by the renowned professor of Japanese history, Edwin Oldfather Reischauer. Born in Japan in 1910 and raised there by his missionary parents, Reischauer, a disciple of Serge Elisseef, the Russian migr who had brought Japanese studies from France to the United States, was a revered figure in Japan. In Washington at the end of the war as the Japan expert in the Army Intelligence Service, he was prominent among the influential voices persuading the Pentagon to remove the ancient capital of Kyoto from the short list of A-bomb targets. When I encountered him he was in his late forties, a tall, handsome man who somehow looked Japanese, particularly about the eyes, cool and assured, intimidating in his gracious way.

Reischauer taught us grammar from a book that had been designed to train interrogators in the Occupation: we learned how to count battalions and heavy artillery and how to say sweeping for land mines. Our drill instructor was a mysterious young woman named Rei Sasaguchi who was working on her dissertation in art history. I was in love with her; when she pointed to me to parrot a sentence my tongue tied. One day we were practicing gerundial verbs: Boarding the _____, I rode to town. When it was my turn I used what I believed to be the English loanword for bus, busu. Miss Sasaguchi laughed prettily and said the word I had chosen meant an ugly hag: Boarding an ugly hag, I rode to town. My mistake, and my scarlet face, became a standing joke in the class.

My classmates were all graduate students. A number of them had lived in Asia and had Chinese or Japanese wives. They ate lunch with chopsticks from lacquer boxes they brought from home, kept their pens and pencils in brocade bags, and carried their books in silk furoshiki. In their presence I, too, was able to feel identified with the society I was studying but had never experienced. I shared little of my life at the Yen-ching with my friends in artsy Adams House, who were reading Kant or Camus or Chaucer. I did take them to see Marlon Brando in Sayonara when it opened in Harvard Square; I felt proprietary about the film, and proud, sitting in the dark, to be offering a tour of my Japan. The film was a hit among us; for years afterward Brandos drawled assurance to the Takarazuka dancer Hanaogi at Red Buttonss pied--terre in Kyoto became part of our standard repartee: But, Lloyd-san, what will our children be? Theyll be half you and half me, darlinhalf yaller and half white!