To Vicki, George and Tess

Arron Hewett

To James, Mum (Margaret) and Andy

Louise Macfarlane

Contents

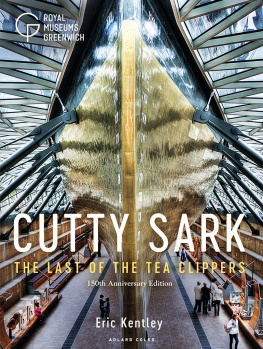

Cutty Sark is a ship like no other. She is the worlds sole surviving extreme clipper. Built in 1869 midway through Queen Victorias era-defining reign, the ship both contributed to and benefited from the Victorian age. The Industrial Revolution, which made Britain the workshop of the world, coincided with a population explosion that would take the number of people in Britain from roughly ten million at the turn of the century to over 22 million by 1870. Sweeping economic reform, gradual adoption of free trade and colonial expansion meant that huge markets became available to British business while key trade routes were protected. Britains dominance of the seas as the worlds foremost shipbuilding nation, with the largest navy and merchant fleet on the globe, coincided with a period of relative peace. Revolution, reform and expansion had set the scene for a record-breaking ship.

This book will explore how all the components came together to enable Cutty Sark , a ship that was built just as steamships were beginning to come into their own, to flourish. By the time she entered the China tea trade, clipper ships and free trade in China had been established for more than a quarter of a century Cutty Sark was late to the party. What was it about her timing, her design and command, and simple good fortune that enabled a ship that was built by relative unknowns to forge a reputation that stands today? The ship that now rests on the banks of the river upon which much of her business was conducted, in a city that was once the capital for a quarter of the worlds population, has had a long and varied life. She was Ferreira a Portuguese general cargo carrier for 26 years; a training ship for naval and mercantile cadets for more than 25 years; and a museum ship for over 60 years. But it was during her first years as a British merchant ship, under the red ensign, that she forged a reputation that would ensure her future survival. It is for this reason that this book will focus upon her earlier years: 186995.

Cutty Sark and the Tea Trade

Cutty Sark was built for the China tea trade, but tea did not reach British shores until the mid-seventeenth century. Initially popularised for its medicinal qualities, it was not long before it became the beverage of choice. Coffee houses sprang up across Europe to entertain the emerging chattering classes, and tea shops soon joined them. In 1660, the famous diarist Samuel Pepys wrote: I did send for a cupp of tee (a China drink) of which I have never tasted before. With the marriage of King Charles II to Catharine of Braganza in 1662, the fashion for drinking tea was truly established. Tea had been popular in Portugal and the Netherlands for half a century before it reached Britain. The new Portuguese queen brought with her not only a taste for tea but two chests of this exotic leaf and the territory of Bombay (Mumbai).

The Opium Wars

The first shipment of tea to Britain was unloaded by the Honourable East India Company in 1669. Established in 1660, the company was formed to challenge the dominance of trade in the East held by the Dutch, Portuguese and Spanish. With bases in Calcutta (Kolkata), Madras (Chennai) and Bombay (Mumbai), the company was awarded the monopoly on all imports from east of the Cape of Good Hope. Exotic goods such as spices, dye, silk and finally tea became popular commodities. The companys monopoly kept prices high, but a heavy tax was also imposed on this new drink. By 1689, one pound in weight of tea would cost the equivalent of a workers weekly wage. The tax, however, was largely ineffective as it gave ample impetus to tea smuggling, which fed a growing demand. Light and easy to transport, more tea entered Britain illegally than was unloaded by the East India Company during this period. The majority of smuggled tea came via the Netherlands, whose own Dutch East India Company had first introduced the drink to Western Europe at the turn of the seventeenth century. Floundering, the British government attempted to ban all Dutch imports. This was as ineffective as the tax. It was not until 1784, and the introduction of the Commutation Act, that smuggling was finally put to an end and the companys monopoly protected. The act slashed duties on tea from 119 per cent to 12.5 per cent, and consumption of the beverage rocketed.

While the East India Company held the monopoly in the trade of tea, the monopoly on its supply was retained by China. However, the Chinese authorities had no interest in importing goods from the West and sought payment only in silver, creating an imbalance that could not be sustained. Britains policy of mercantilism imposing high taxes to limit imports in favour of maximising exports sought to restrict the amount of silver entering a territory where it was unlikely to get it back. They needed to find another commodity that the Chinese would buy.

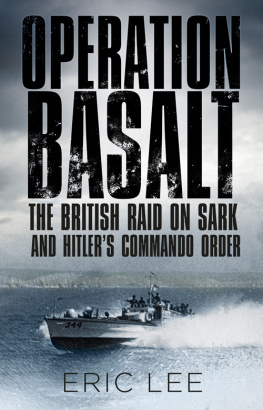

The company therefore began to grow and sell Indian opium to merchants for smuggling into China. The opium was paid for in silver, which soon made its way back into the pockets of the Western tea merchants. Despite prohibiting the sale of opium in 1799, the Chinese authorities were unable to enforce the ban and by the 1820s the opium trade was an extensive industry resulting in a huge addiction problem. In 1839, in a bid to control the situation, the Chinese authorities seized and destroyed the years tea crop at Canton (Guangzhou). The British retaliated: accepting the merchants argument that this was a violation of free trade, the government acted swiftly and decisively. The First Opium War (183942) was a demonstration of the power of the Royal Navy in what has been termed gunboat diplomacy. Following an attack on Canton and the occupation of Shanghai, the Chinese emperor was forced to sign the Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing) in 1842. The treaty ceded Hong Kong to the British and opened the ports of Canton, Amoy (Xiamen), Foochow (Fuzhou), Ningpo (Ningbo) and Shanghai to unrestricted trade. But it did not end there. A spurious accusation of piracy against a Hong Kong-registered ship a couple of years later escalated into another war. French, American and Russian forces joined the fray and the Second Opium War (185660) ended with a devastating defeat for the Chinese. The opium trade was then legalised and did not cease until 1917; a huge amount of compensation was demanded; and more ports were forced to open up. Hankow (Hankou), the tea capital of China, was among them.

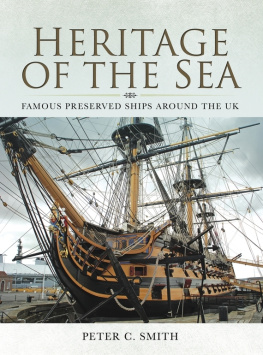

Clipper Ships

The clipper ship revolution began in the United States of America. Baltimore clippers were small, agile, fast-sailing vessels similar to those that had so successfully eluded the Royal Navy during the 1812 war with Britain. Often thought to have taken their name from their ability to go at a clip, these new vessels were best suited to trades reliant upon speed rather than those reliant upon cargo space. The First Opium War, the discovery of gold in California in 1849 and the same discovery in Australia in 1851 all provided impetus for a shipbuilding boom. Chinese ports were now open, and the gold rush offered the potential for instant wealth. Both meant that orders for vessels flooded the American market. Spurred on by the need to obtain even a slight advantage, American ship designers began to apply the innovations of the Baltimore clippers to larger ships. John Willis Griffiths, based in New York, had developed his own testing tank for experimenting with his ideas. He was convinced that a long, gracefully tapered hull and narrow bow exceedingly diminishes the resistance with which [a vessel] moves. His experiments led him to believe that conventional wisdom should be turned on its head. In order to achieve a vessel capable of great speeds, the traditional ship shape the cods head and mackerel tail should effectively be reversed. Griffiths believed that a great improvement on the cods-head-shaped round bow, which smacked into the waves and rode up over each crest, would be a sharp bow that could simply cut through the water. Similarly, he took issue with the belief that the mackerel-tail-shaped narrow stern left a clean wake, suggesting instead that it created a drag. He proposed that a fuller shape and long, thin hull would allow water to run smoothly astern.