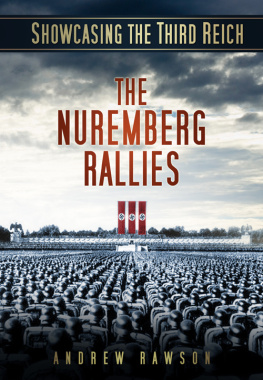

Every September between 1933 and 1938 the area around Dutzendteich Lakes, two miles south east of Nurembergs old town, was the centre of attention in Nazi Germany. Tens of thousands of Party members descended on the city to attend the Party rally and participate in the range of meetings, parades and march pasts held across the city and the Rally Grounds. Over the years thousands of labourers worked on a range of projects, both improving existing structures and building new ones, until the Rally Grounds covered 11km. Thousands of others worked on the railways and the roads that brought the visitors to the Dutzendteich area or on the accommodation, the hotels and campsites.

The Nazis used the rallies to get their messages across to their supporters face-to-face in an age before television and the internet. They also used their meetings and parades to strengthen the sense of unity across the Party and across the Reich. They were a defining point in the Nazi calendar, one which the visitors went away from invigorated and ready to face new challenges set by their leaders.

How the rallies expanded from a single day event into a week-long extravaganza and how the grounds expanded from a couple of existing arenas into Albert Speers vision for a huge range of structures is described in this book. Biographies of the architects are also included. The different organisations which took part and their leaders are discussed as well as the full programme of parades, march pasts and meetings.

It is hoped that the reader will gain an insight into the men who brought the rallies to Nuremberg and their motives. The Nuremberg Laws, the Nazis way of dividing society into Aryans and non-Aryans, are part of the story and can be considered as an early step on the road to the Holocaust. Finally, what can still be seen today in Nuremberg is described and a tour around the Rally Grounds and the city centre is suggested.

C ONTENTS

1

What follows is a brief description of the rise of the Nazis between the first rally in 1923 and the final, cancelled rally in 1939. It outlines each rally, illustrating how it developed from a simple day-long fund raising event into a week-long programme of activities.

THE FIRST PARTY CONGRESS (MUNICH, 27 JANUARY 1923)

20,000 supporters attended the first Party Rally in Munich on 27 January 1923. The SAs first four standards were consecrated during an ad-hoc ceremony; such ceremonies became an important part of future rallies. The Rally was a financial success and the NSDAP leaders decided to hold a second convention in the autumn.

THE GERMAN DAY RALLY (NUREMBERG, 12 SEPTEMBER 1923)

A two-day event was held in Nuremberg to make it easier for northern members to attend and it was called German Day to increase the appeal to the public. The rally focused on remembering two German military triumphs; the Battle of Sedan in 1870 against the French during the Franco-Prussian War and the Battle of Tannenberg against the Russians in 1914 during the First World War.

The SA demonstrated their discipline and comradeship, aiming to attract new members from other right-wing groups, and the highlight was a parade past Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and Julius Streicher in the Hauptmarkt. Eight weeks later, the three tried to seize power in Munich but the uprising failed and Hitler was jailed for five years in April 1924.

Alfred Rosenberg stood in as leader of the NSDAP but he was neither a leader nor an administrator and the Party soon broke up. The National Socialist Freedom Party was formed in April 1924 and a month later nearly two million people voted for it, putting 32 delegates in the Reichstag. Members of the SA also continued to meet under the guise of sports clubs, singing clubs and rifle clubs.

The march through the centre of Nuremberg was one of the early rituals.

THE SECOND PARTY CONGRESS, THE REFOUNDING CONGRESS (WEIMAR, 34 JULY 1926)

Hitler was released from prison on 24 December 1924 after serving only eight months. The ban on the NSDAP was lifted on 16 February 1925 and Hitler began work on uniting the Party across Germany. He faced opposition from Gregor and Otto Strasser in Berlin but they were brought into line at the Bamberg Conference on 14 February 1926.

Although the Party did not have enough funds to hold a Party Rally in 1925, members worked hard to raise money for one the following summer. Hitler was banned from speaking in Bavaria so it was moved to Weimar, Thuringia. The choice was a pragmatic one. Bavaria was out of bounds and the Bavarians in the Party did not want to hold the rally in Berlin. Weimar was the city where the National Congress had met in 1919 to establish a new post-war republic; the German Reich is often referred to as the Weimar Republic.

A new ceremony became a centrepiece of the rally when the battle-scarred flag carried during the 1923 Munich Putsch was paraded as a sacred relic. As the faithful looked on, Hitler held the Blood Flag, as it was called, and seized each new unit flag in turn, in a pseudo-religious consecration ceremony.

THE THIRD PARTY CONGRESS, THE DAY OF AWAKENING (NUREMBERG, 1921 AUGUST 1927)

When Bavaria lifted its ban on Hitler speaking, the NSDAP returned to Nuremberg for their next annual congress. The citys favourable geographic situation and good rail links made it easier for supporters to get to the rally. It was a neutral city, which neither alienated the Bavarians nor the Prussians. Luitpold Grove (Luitpoidhain) was a practical meeting place and while Franconia had a well organised NSDAP under Julius Streicher, the Nuremberg police chief, Benno Martin, was sympathetic to the Nazi cause.

While the 1927 rally was a success, the NSDAP was spending all its money on campaigning. There was no rally in 1928 and the party instead focused on its leader conference in Munich.

THE FOURTH PARTY CONGRESS, THE DAY OF COMPOSURE (NUREMBERG, 2 AUGUST 1929)

By September 1929 the Party had increased its membership and subscriptions sufficiently to stage another rally. The NSDAP had recently allied itself with the German National Peoples Party (DNVP) to campaign against the Young Plan, a new financial plan designed to restructure Germanys war reparations. While the alliance did not last for long, the campaign increased the NSDAPs exposure due to favourable coverage in Alfred Hugenbergs newspapers.

The early rallies were disorganised affairs compared to the later ones.

Thousands of NSDAP members gathered in Nuremberg but the parades and marches drew the attention of the local Communist and Social Democrat supporters. There were clashes across the city, leaving the police struggling to keep control and street battles left two dead and many injured, including five policemen. The riots were covered extensively in newspapers, giving the Rally free publicity.

The Rally caused so much trouble that the city council banned future political conventions. They need not have bothered; the NSDAP was again out of money because campaigning had reached fever pitch. It had to be satisfied with holding leader conferences.

THE FIFTH PARTY CONGRESS, THE RALLY OF VICTORY (31 AUGUST3 SEPTEMBER 1933, NUREMBERG)

Between August 1929 and August 1933 the NSDAP rose from strength to strength on the back of political unrest in Germany. It started with the Wall Street Crash in October 1929, when the value of the United States stock market fell rapidly, seriously undermining Germanys weak economy. As unemployment rose and businesses closed, support for Germanys democratic parties declined as voters looked to radical political parties for answers.

Next page