PROLOGUE

I t is Friday morning, 8 A . M . I hear a key turn in the front-door lock of my Los Angeles home. Mara del Carmen Ferrez, who cleans my house every other week, opens the door. She walks into the kitchen.

Carmen is petite, intelligent, and works at lightning speed. At this early hour I am usually in a frenzy to get out the door and rush to my office. But on days when Carmen arrives, she and I shift gears. Carmen loiters in the kitchen, tidying things. I circle around her, picking up shoes, newspapers, sockstrying to give her a fighting chance at cleaning the floors. The ritual allows us to be in the same room and talk.

On this morning in 1997, I lean on one side of the kitchen island. Carmen leans on the other side. There is a question, she says, that she has been itching to ask. Mrs. Sonia, are you ever going to have a baby?

Im not sure, I tell her. Carmen has a young son she sometimes brings to watch television while she works. Does she want more children? I ask.

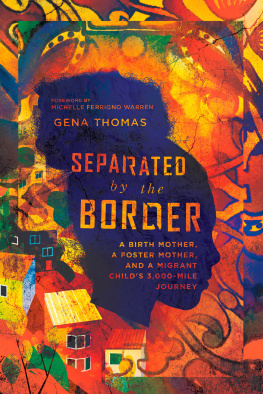

Carmen, always laughing and chatty, is suddenly silent. She stares awkwardly down at the kitchen counter. Then, quietly, she tells me about four other children I never knew existed. These childrentwo sons and two daughtersare far away, Carmen says, in Guatemala. She left them there when she ventured north as a single mother to work in the United States.

She has been separated from them for twelve years.

Her youngest daughter, Carmen says, was just a year old when she left. She has experienced her oldest boy, Minor, grow up by listening to the deepening timbre of his voice on the telephone. As Carmen unravels the story, she begins to sob.

Twelve years? I react with disbelief. How can a mother leave her children and travel more than two thousand miles away, not knowing when or if she will ever see them again? What drove her to do this?

Carmen dries her tears and explains. Her husband left her for another woman. She worked hard but didnt earn enough to feed four children. They would ask me for food, and I didnt have it. Many nights, they went to bed without dinner. She lulled them to sleep with advice on how to quell their hunger pangs. Sleep facedown so your stomach wont growl so much, Carmen said, gently coaxing them to turn over.

She left for the United States out of love. She hoped she could provide her children an escape from their grinding poverty, a chance to attend school beyond the sixth grade. Carmen brags about the clothes, money, and photos she sends her children.

She also acknowledges having made brutal trade-offs. She feels the distance, the lack of affection, when she talks with her children on the telephone. Day after day, as she misses milestones in their lives, her absence leaves deep wounds. When her oldest daughter has her first menstruation, she is frightened. She doesnt understand what is happening to her. Why, the girl asks Carmen, were you not here to explain?

Carmen hasnt been able to save enough for a smuggler to bring them to the United States. Besides, she refuses to subject her children to the dangerous journey. During her own 1985 trek north, Carmen was robbed by her smuggler, who left her without food for three days. Her daughters, she fears, will get raped along the way. Carmen balks at bringing her children into her poor, drug- and crime-infested Los Angeles neighborhood.

As she clicks the dishwasher on, Carmen, concerned that I might disapprove of her choice, tells me that many immigrant women in Los Angeles from Central America or Mexico are just like hersingle mothers who left children behind in their home countries.

Whats really incomprehensible, she adds, are middle-class or wealthy working mothers in the United States. These women, she says, could tighten their belts, stay at home, spend all their time with their children. Instead, they devote most of their waking hours and energy to careers, with little left for the children. Why, she asks, with disbelief on her face, would anyone do that?

The following year, in 1998, unannounced, Carmens son Minor sets off to find his mother. Carmen left him when he was ten years old. He hitchhikes through Guatemala and Mexico. He begs for food along the way. He shows up on Carmens doorstep.

He has missed his mother intensely. He could not stand another Christmas or birthday apart. He was tired of what he saw as his mothers excuses for why they could not be together. He had to know: Did she leave Guatemala because she never truly loved him? How else could he explain why she left?

Minors friends in Guatemala envied the money and presents Carmen sent. You have it all. Good clothes. Good tennis shoes, they said. Minor answered, Id trade it all for my mother. I never had someone to spoil me. To say: Do this, dont do that, have you eaten? You can never get the love of a mother from someone else.

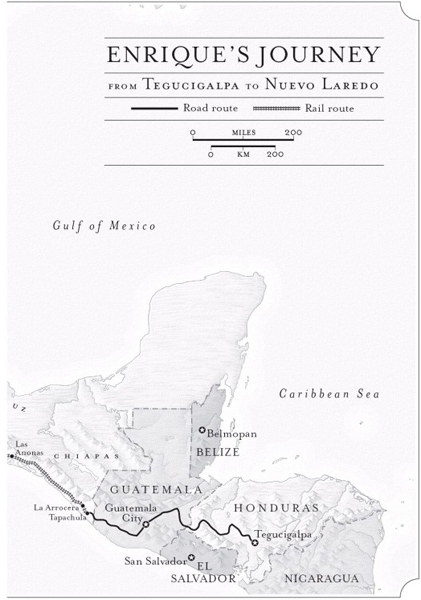

Minor tells me about his perilous hitchhiking journey. He was threatened and robbed. Still, he says, he was lucky. Each year, thousands of other children going to find their mothers in the United States travel in a much more dangerous way. The children make the journey on top of Mexicos freight trains. They call it El Tren de la Muerte. The Train of Death.

A COMMON CHOICE

I was struck by the choice mothers face when they leave their children. How do they make such an impossible decision? Among Latinos, where family is all-important, where for women motherhood is valued far above all else, why are droves of mothers leaving their children? What would I do if I were in their shoes? Would I come to the United States, where I could earn much more money and send cash back to my children? This would mean my sons and daughters could eat more than sugar water for dinner. They could study past the third grade, maybe even finish high school, go on to university classes. Or I could stay by my childrens side, relegating another generation to the same misery and poverty I knew so well.

I was also amazed by the dangerous journey these children make to try to be with their mothers. What kind of desperation, I wondered, pushes children as young as seven years old to set out, alone, through such a hostile landscape with nothing but their wits?

The United States is experiencing the largest wave of immigration in its history, a level of newcomers that is once again transforming the country. Each year, an estimated 700,000 immigrants enter the United States illegally. Since 2000, nearly a million additional immigrants annually, on average, have arrived legally, or become legal residents. This wave differs in one respect, at least, from the past. Before, when parents came to the United States and left children behind, it was typically the fathers, often Mexican guest workers called braceros, and they left their children with their mothers. In recent decades, the increase in divorce and family disintegration in Latin America has left many single mothers without the means to feed and raise their children. The growing ranks of single mothers paralleled a time when more and more American women began working outside the home. There is an insatiable need in the United States for cheap service and domestic workers. The single Latin American mothers began migrating in large numbers, leaving their children with grandparents, other relatives, or neighbors.