In memory of my mother,

Lorine Elizabeth Nordland

With loves light wings did I oerperch these walls;

For stony limits cannot hold love out,

And what love can do, that dares love attempt;

Therefore thy kinsmen are no stop to me.

ROMEO AND JULIET, ACT 2, SCENE 2

CONTENTS

Guide

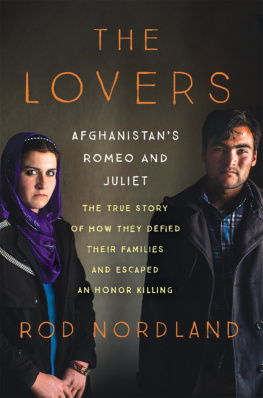

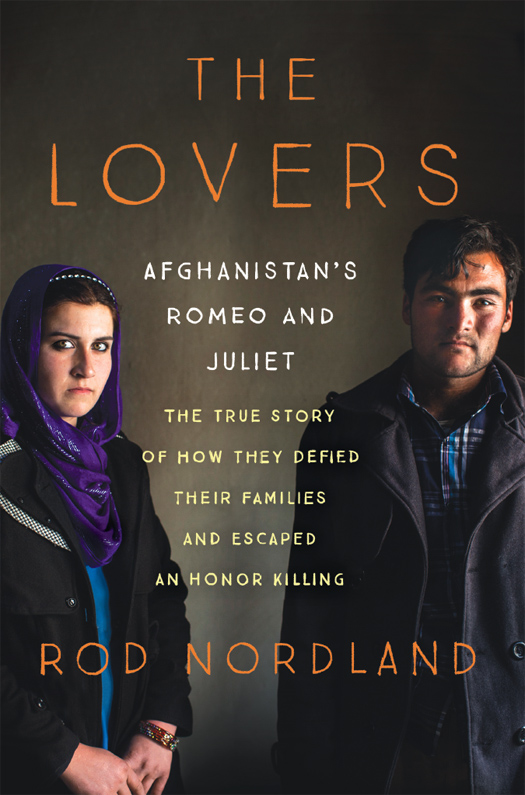

Zakia, Alis lover, third daughter of Zaman and Sabza;

and

Mohammad Ali, Zakias lover, third son of Anwar and Chaman.

THE AHMADIS

Mohammad Zaman, Ahmadi family, Kham-e-Kalak village, father of Zakia;

Sabza, his wife, mother of Zakia;

Gula Khan, his second son, older brother of Zakia;

Razak, his fourth son, youngest brother of Zakia.

THE SARWARIS

Mohammad Anwar, Sarwari family, Surkh Dar village, father of Ali;

Chaman, his wife, mother of Ali;

Bismillah, his eldest son, brother of Ali;

Ismatullah, his second son, brother of Ali;

Shah Hussein, his nephew, cousin of Ali.

OTHERS

Najeeba Ahmadi, director, Bamiyan Womens Shelter;

Fatima Kazimi, Bamiyan Province director, Ministry of Womens Affairs;

Manizha Naderi, executive director, Women for Afghan Women;

Shukria Khaliqi, lawyer, Women for Afghan Women.

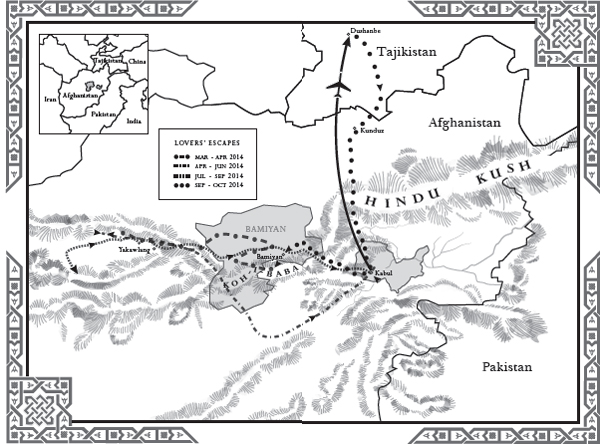

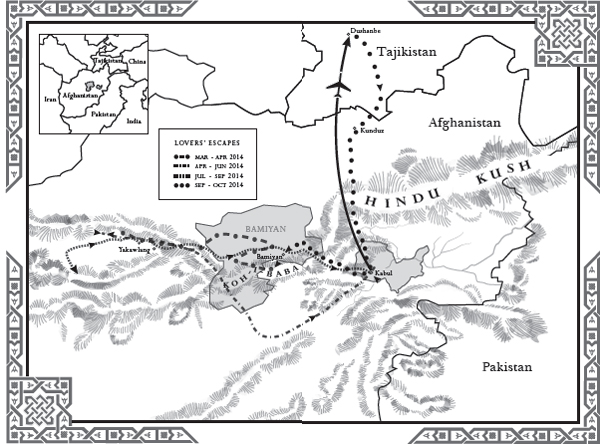

Zakia and Ali escaped captivity and eloped, but were hunted by both Afghan police and vengeful family members. They managed to stay one step ahead of their pursuers in the rugged mountains of central Afghanistan, traveling by foot, in cars and buses, and even by air to neighboring Tajikistan. The couple spent their honeymoon in caves and their first anniversary still in hiding.

It was a cold clear February day when we finished our first visit to see Afghanistans most famous young lovers and went out to what passes for an airport in Bamiyan towna broad cinder runway with a fine view of the cliff niches that once held the Great Buddhas. There was a cyclone fence around a few shipping containers, one of which was the waiting room, another the office of airport management. The United Nations and a private Afghan company, East Horizon Airlines, which had some aging Russian turboprop craft, flew in only a couple of times a week so there wasnt much point in real infrastructure. I remember sitting in the waiting room container next to a bukhari, the flimsy, usually rusted stove that burns everything from wood and chips to coal and diesel oil, trying to stay warm as I wrote my first article for the New York Times about the lovers. I thought, what a great story, though sad, and with a follow-up that was a death foretold. I expected that the next and final article would be about how the girls family came one night and dragged her from the shelter or how, out of loneliness and despair or a misguided willingness to believe in her brothers promises, she would emulate the example of so many other Afghan girls who left shelters to return to their families, believing theyd be safe, and were never seen alive again. We would all be outraged and then turn the page.

Thats how such stories usually end, but I was wrong, and theirs was just beginning.

Her name was Zakia. Shortly before midnight on the freezing-cold eve of the Persian New Year of 1393 she lay fully clothed on her thin mattress on the concrete floor and considered what she was about to do. She had on all her colorful layersa long dress with leggings under it, a ragged pink sweater, and a long orange-and-purple scarfbut no coat, because she did not own one. The only thing she did not have on were her four-inch open-toed high heels, since no one would wear shoes indoors in Afghanistan; instead the heels were positioned beside her mattress, neatly left shoe on the left, right on the right, next to the little photograph she had of Ali, the boy she loved. It was not the best escape gear for what she was about to doclimb a wall and run off into the mountainsbut it would soon be her wedding day, and she wanted to look good.

That night of March 20, 2014, was not the first time Zakia had contemplated escaping from the Bamiyan Womens Shelter, which had been her home, her refuge, and her prison for the past six months, since the day she ran away from home in the hope of marrying Ali. Always before, her nerve had failed her. Two of the other girls who shared her room were awake as well, but they would make no move unless she did first. Though Zakia was still terrified and did not know if she had the courage to leave, she felt she was fast running out of both time and opportunity.

This was no small thing, although Zakia was then eighteen and legally an adult, a voluntary shelter resident rather than a prisoner, and in the eyes of Afghan law she was free to go whenever she pleased. But the law is only what men make it, and nowhere is that more true than in Afghanistan. What Zakia was about to do would change not only her life and that of Ali, who waited for her call on the other side of the Bamiyan Valley. She understood that it would change the lives of nearly everyone they knew. Her father, Zaman, and her mother, Sabza; her many brothers; and her male first cousinsthey would all give up their farm and devote their lives to hunting down Zakia and Ali, publicly vowing to kill them for the crime of being in love. Alis father, Anwar, would be forced into such debt that his eldest son would lose his inheritance, and most of the familys crops would be forfeited for years to come. Others would be touched in unexpected ways. A woman named Fatima Kazimi, who ran the womens ministry in Bamiyan and had recently saved Zakia from being killed by her family, would flee to exile in Africa. Shmuley Boteach, a rabbi from New Jersey who that night scarcely knew how to pronounce Zakias name, would end up consumed by her case, lobbying at the highest levels of the United States government to intervene on her behalf. In the course of it all, this illiterate and impoverished girl who did not know her numbers up to ten and had never seen a television set would become the most recognizable female face on the Afghan airwaves. She would become a hero to every young Afghan woman who dreams of marrying the one she loves rather than the one chosen for her by her family, sight unseen. To the conservative elders who preside over their countrys patriarchy, however, Zakia would become the fallen woman whose actions threatened the established social order, actions that were yet more evidence of the deplorable interference of foreigners in Afghanistans traditional culture.

That is where I came in, because the articles I had no idea what they were up to and was three days travel away from them elsewhere in Afghanistan. We were the last people on one anothers minds.

I had visited them in Bamiyan only a month earlier, so when I later heard what had happened, it was easy enough to picture the scene. For some reason the words of the Robert Browning poem Porphyrias Lover sprung to mind, perhaps because it was about an impatient lover awaiting the arrival of his beloved:

The rain set early in to-night,

The sullen wind was soon awake,

It tore the elm-tops down for spite,

And did its worst to vex the lake:

I listened with heart fit to break.

For elms, substitute the silver birches that are arrayed in proud double rows extending from the southern side of the Bamiyan Valley, where the womens shelter was, along farm lanes cutting down toward the river that runs through it. Tall and slender, the birches are reminiscent of the needle cypresses that flank the lanes of Etruria, except that the silvery backs of their leaves and the mica-like bark all seem to sparkle even in the starlight. Bamiyan town is the capital of the province of the same name, a highland area on the far side of the Hindu Kush mountains, a place of green valleys between barren and forbidding ranges a long way from anywhere. The town is ranged over two broad flatlands on the southern side of the Bamiyan Valley; the lower one holds the ancient town, a collection of mud buildings little different from those there thousands of years ago, interspersed with newer concrete ones, the metal doors on shops in the bazaar painted in primary colors, and, not far below that, the river, still with patches of ice in the middle and snow on its banks.