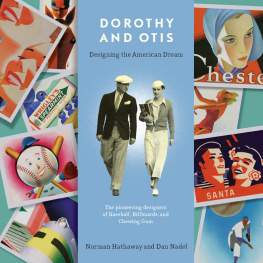

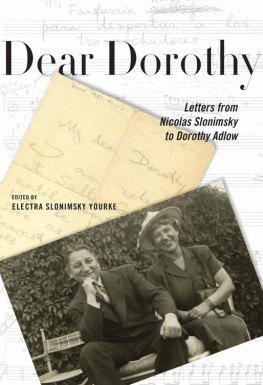

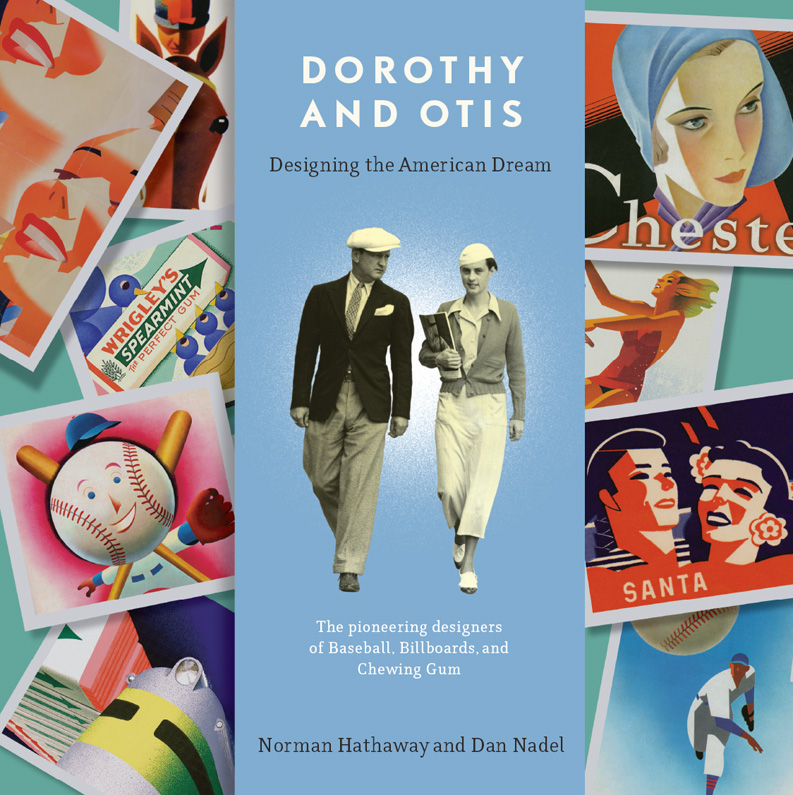

Dorothy and Otis, Morgan Hill, California. Circa 19281929.

Contents

Dorothy and Shep pose with their beloved Packard Roadster, circa late 1920s.

Dorothy and Otis Shepard are responsible for some of the most memorable designs of the twentieth century. They worked both as a team and individually, introducing modernism to American design and defining the look of early billboards, Wrigley Chewing Gum, the Chicago Cubs, and Catalina Island, a resort island off the coast of California. With an eye for the big picture and the skill to create stunning illustrations and lettering, they implemented innovative campaigns through paper advertisements and signage. They also designed clothing, interior spaces, and even the Cubs stadium. Their work was ubiquitous from the 1920s to the 1960s, and while their lives were as remarkable as their workglamorous, successful, and progressivetheir names are all but unknown today.

So how did we arrive at this book? Norman started it. A longtime aficionado of unheralded graphic culture, he authored Overspray: Riding High with the Kings of California Airbrush Art, which examines the history of 1970s commercial airbrush art in Los Angeles. I published it through my now-defunct imprint, PictureBox. The airbrush has a long history, some of which leads back to Otis Shepard, Shep, who was one of the first Americans to truly master it for the creation of luminous images.

Norman knew of Shep before he created Overspray, having come across instructional texts by Shepard in nearly every how-to-airbrush book hed picked up as a kid, and all of the artists featured in Overspray cited Shep as an influence. But when researching the designer, Norman found very few images of him or text written about him. So, as is his wont when exploring a subject, he started a Flickr group to house the images he could find. There he put all the ones by Shep his research turned up, and one dayto his shockSheps granddaughter, Erin, commented on an image. She mentioned her grandmother, Dorothy Shepard, in the post. Norman had been researching Shep, but hed never heard of Dorothy.

After a few exchanges with Norman, Erin began posting work made by Dorothy, and it was immediately apparent that she had been a huge talent in her own right. Norman wanted to find out more, and so, at Erins urging, he called Erins father (Shep and Dorothys son), Kirk. Kirk told stories that left no doubt that Dorothy and Shep had a story far more thrilling than history documentedone of artistry, sure, but also of glamour and modernity, baseball and Americana, and the first great female talent in North American modernist graphic design. To Normans great excitement, Kirk revealed that he had loads of ephemera documenting his parents work and personal lives.

Shortly after his phone call with Kirk, Norman invited me into his discovery, and we decided to explore it together. Erin, who lives in Paris, visits her father in Arizona once a year, and the four of us decided to converge at Kirks house in August 2010. Both Norman and I vividly remember walking through Kirks door and being stunned. There, on the front table, was his parents legacy: scrapbooks piled high; portfolios bulging with posters and drawings; notebooks; file folders; and boxes of negatives. When we saw that huge trove, we knew we had material for a book that was not just about the design of iconic American images but also about the lives of their designersfor these were dynamic people who had created unparalleled work at a time when the nation was on a social and economic roller coaster. Amazingly, Dorothy had kept meticulous records of her life and Sheps, as if she knew someone might one day come looking for them.

So how is it that Dorothy and Shep are almost unknown today? Well, the medium that initially made them famous, the billboard, lost its glamour once the use of color became the norm in magazines, and later radio and television took over the airwaves and advertising budgets. Dorothy and Shep didnt produce the kind of design work that is most frequently lionized, such as stand-alone wall posters or book covers. And because billboard designs were rarely archived or credited to their designers, little exists in the design history books about them or the people who made them. The Shepards also created almost too much work in too many mediums for anyone to grasp the entirety of their achievements. Baseball historians might know the Cubs work and graphic design historians might know the Wrigley billboards, but no one besides Kirk and Erin seems to know that the designers diversified so extensively. In the first half of the twentieth century, that kind of portfolio seemingly couldnt exist outside of Europe. Dorothy and Shep also worked on the West Coast and in Chicago, places that have not received the same level of attention as work made in New York; even today, there is much design that remains unexamined from those regions. All these reasons, and perhaps the lack of a concrete legacy of followers, contributed to the Shepards being left out of most design history books. This book aims to right that wrong and bring the entirety of the Shepards talents back into focus.

A note on sources:

Our knowledge of the Shepards lives together and apart comes from the sources noted in the text, many of them tucked into Dorothys scrapbooks, and from our multiple interviews with Kirk and Erin Shepard. Where no source is cited, the information came from Kirk and Erin Shepard.

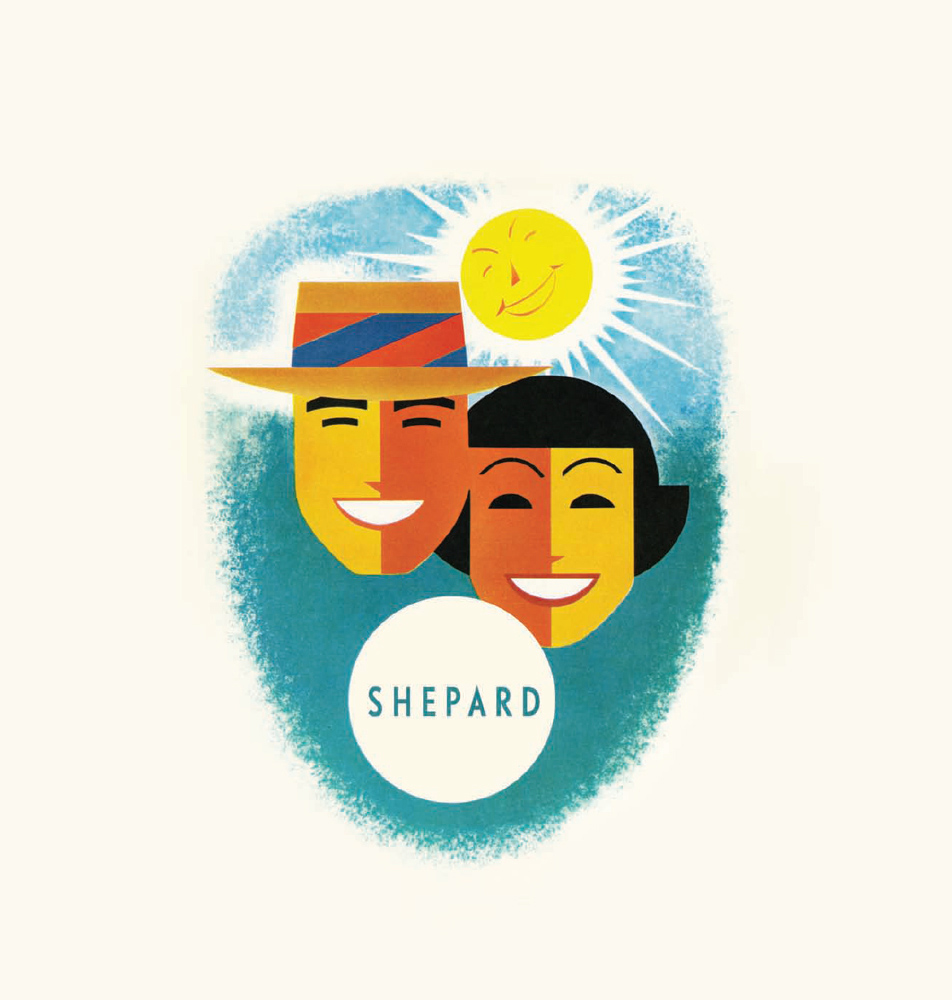

An undated photograph of Shep.

The stories of Otis Shepards early life are almost too over-the-top to believe. What was documented in various profiles published during his life and in Otiss own colorful autobiographical writings is vastsometimes contradictory, but always entertaining.

Otis was born in 1894 in Smartville, Kansas. His mother, Nancy, was notoriously tough and was said to have killed a Native American who wandered into her kitchen one afternoon. His father, Lucius Franklin Shepard, was either a traveling salesman or a circus performer; his array of unusual skills included specialties in sword swallowing and fire eating. Some accounts claim that Lucius was an expert sprinter, others that he was a fabulous tenor singer or skilled pool player. A 1945 article in Sporting News quotes Otisor Shep, as he was nicknamedstating that one of his earliest memories was watching his father run 4560 balls to the distress, humiliation, and amazement of some local bumpkin.

In 1906, at age twelve, Shep left home, having completed only the fourth grade. He landed in El Paso, Texas, where he briefly worked at the Humphries Photoengraving Shop as an errand boy. I was privileged to waste paper and ink in a one-man art department, he later wrote. This was likely his first foray into the world of commercial art endeavors. After this, he was an assistant to a scenic artist and became interested in the stage. Then, in the latter part of 1906, he moved to California, settling in Napa Valley, where he worked with his uncle, who maintained vineyards. There, out in the quiet countryside, Shep and four-horse teams hauled wine between small and large wineries. After a year of this hard physical labor, he went south to San Francisco, where he secured jobs in the bubbling media world. Shep worked first at the