All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

PREFACE

Some 620,000 people died in the United Statess costliest war, all of them Americans killed by other Americans. For the first time anywhere, populations preyed on each other with industrialized efficiency, attracting the attention of a world keen on witnessing the birth of modern slaughter. At stake were issues of profound importance: basic human freedom, sovereignty, the definition of self-government, and the limits of revolution, to name a few. It wasisthe defining watershed in the nations history. No wonder were preoccupied with it.

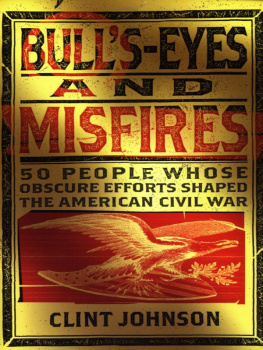

But our fascination goes beyond that. In addition to being the crucible in which America was reshaped, the Civil War was an enthralling drama. Its scale and ferocity were Homeric, its tragedies Shakespearean. And its endlessly varied characters seem to have walked off the pages of literatures most imaginative fiction.

Dan Sickles, for instance, was one of the nineteenth centurys most notorious rogues. But he went on to become a political general whose performance in the wars greatest battle produced controversy equal to his outrageous behavior in civilian life. Thomas Jackson, by contrast, would have disappeared beneath the pages of posterity as a backwoods eccentric, middling teacher, and religious zealot. War, however, afforded his bizarre suite of abilities an opportunity to make military history, vaulting this humorless oddball into the pantheon of hallowed warlordsan unlikely fate indeed, given the material of which he was made. Such sensational lives are a dime a dozen in the War Between the States, presenting a panoply of weakness, heroism, triumph, waste, irony, idiocy, and even romance. Their stories are inherently irresistible, and not always because they performed a tremendous deed or won a crucial battle. Sometimes they wore carpet slippers into combat, blew off the president with astounding impropriety, had a nervous breakdown, or carried a hambone in their pocket. Fascinating wears all sorts of faces.

From the great and famous whose names have become household phrases to the numberless and forgotten whose lives require more effort to reveal, the players in this greatest of American struggles were human beingsflawed, awkward, spontaneous, strange, earnest, neurotic, and often quite smelly. No amount of eulogizing or monument-building can erase this salient fact. And that is as it should be.

INTRODUCTION

On December 2, 1859, Charles Town, Virginia, had a hanging. The condemned was a man named John Brown, whose recent invasion of Virginia had polarized a nation already quaking with ideological friction. Seven weeks before, he had descended with a small band of armed partisans on Harpers Ferry with the intention of capturing the armory there and igniting a slave revolt, hoping to precipitate a crusade to destroy the Souths peculiar institution. The adventure, unrealistic and poorly planned, failed miserably. Though the armory and arsenal were taken, Brown and his men were eventually surrounded in the towns fire engine house. Marines commanded by Robert E. Lee stormed the place, killing and capturing most of the defenders. Brown was tried for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia and found guilty.

Though his mission had been foiled, the nature of Browns fate was anything but disagreeable to him: the gallows would be as close to a national pulpit as he was ever going to get. He had been committed to the complete annihilation of slavery for years, at any cost, personifying a furious contempt for compromise that was increasingly claiming both sides of the slavery debate. In Kansas, during the grisly guerrilla conflicts that soaked that state in blood during the 1850s, Brown and his sons had hacked five pro-slavery men to death in retaliation for a notorious raid on the community of Lawrence. For Brown, such crude justice was nothing compared to the gargantuan collective sin of human bondage.

His hanging was by invitation only, and most of the honored spectators were soldiers. Nevertheless, the eyes of the world were on the doomed man, and he made the most of circumstances in the oddly punctuated note he left to his jailers. I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood, he wrote like a prophet.

And so he was. Two years later, in the midst of a terrible war, soldiers put Harpers Ferry to the torch. But the fire engine house where Brown had made his stand remained intact and defiant amongst the smoking rubble, a chilling reminder of the firebrand who foresaw a nations self-mutilation.

Whether you viewed Brown as a traitor, a hero, a fool, a messiah, or a homicidal maniac depended on where you lived and how you felt about the slave issue that had driven him to act. The schism between free and slave states had existed since the previous century. Having failed to deal with it for the sake of sectional harmony, the founding fathers in effect passed the buck to future generations. For more than half a century, the United States carried the controversy westward as new territories were added to the republic. Each became a pawn in the ongoing debate, adding votes in Congress for the side that claimed it. Political bargainsparticularly the Missouri Compromise (1820), the Compromise of 1850, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854)were arranged with the intention of balancing the relative territory and power of slave and free factions, but usually pleased neither. With the passage of time, abolitionist circles became more vocal, more determined against concessions, and more brazen in their extralegal efforts to aid runaway slaves. Incensed by their activities and seeing a growing immigrant North as a threat to the balance of power (by the advent of the Civil War there were four more free states than slave states) and hence to its slave-based economy and culture, the agrarian South cultivated secession from the Union as an increasingly likely option.

It is easy to oversimplify, of course. There were plenty of those in the free North who believed that interfering with the slave laws of Southern states was constitutionally unacceptable. And in areas of the South, some of them quite large, breaking away from the sovereign United States was treasonous, whatever the reason. But these were the exceptions in a mounting tale of angry discord. An immense impasse had been reached between two divergent, irreconcilable, self-righteous cultures.