I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to all those who were so kind as to grant me interviews to help with the research for this book. Their regard, admiration and affection for John Williams made my task of persuading them to do so far easier that I could have imagined. In England, Australia and elsewhere they gave time, offered hospitality and shared their memories with generosity and patience. It was a pleasure and a privilege to meet each and every one of them and I thank them all sincerely. That many of them have become friends is a blessing and a bonus beyond the dreams of the most avaricious banker.

Sadly, some very special people who helped me with their contributions shall not read this book and I pay my humble respects to the memories of Sir John Dankworth, Matcham Skipper, Eric Sykes and Gareth Walters.

The process of actually writing a book and getting it into its final form is very different than researching it and I benefited from great generosity in this phase, too. The professionals at The Robson Press have been just that: generous, indispensable and supportive throughout.

My admiration of the redoubtable Richard Sliwa is matched by my gratitude for his generous provision of the discography included here and Tony Long, friend of many years, is due thanks, too, for accepting being put upon without complaint; he provided assistance and support when it was most needed. My daughter Anna-Marika was always available with encouragement when concentration and inspiration were in short supply and I shall never forget the help I received from Val Doonican, surely one of the nicest human beings ever to draw breath.

Most of all I thank John Williams for his generosity with time and his recollections. Without interference or demands, he has supported and encouraged me along the journey leading to this book and I value his trust, confidence and friendship enormously.

Finally, to my dear patient wife, Eila, who has developed the special discipline needed to live with a writer and stoically tolerated the disruption to our life together for the past few years, kiitoksia paljon!

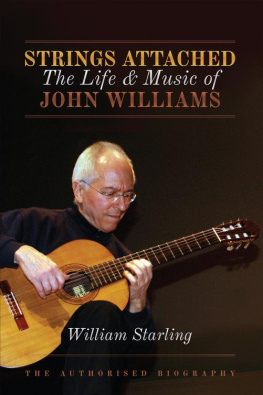

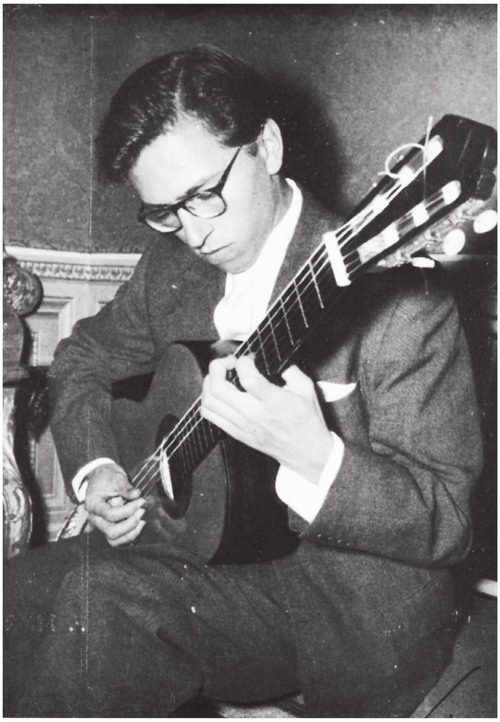

T o do justice, in a single volume, to the life of a decidedly still-active musician with a stellar fifty-year plus career behind him is a tall order. The task becomes even more daunting, however, when the subject has not been content with a linear musical life, achieving and settling for mastery of the path on which he was set as a boy. Not so for John Williams, and consequently there is not just a story to relate but some curious questions to consider. Why, as he reached and exceeded the heights expected of him, did John Williams choose to challenge norms and expectations in repertoire and presentation? Why did he form ground-breaking , perhaps risky collaborations, commission and promote unexpected works and confound orthodoxy in the design of his chosen instrument?

Then there is what lies beyond the music. While this particular life may appear to be neatly bound around with guitar strings, there are other, metaphorical strings extending from the musical core to other, less obvious factors in Johns make-up: his lifelong humanitarian involvement, his pride in being determinedly Australian, and a bloodline that includes a Cockney cabinet-maker and a Chinese barrister. How do these and other such factors contribute to defining John Williams?

Woven through much of the above and perhaps shedding some light is the profoundly influential role of Johns charismatic father and teacher, Len, whose own eventful story sets the scene. This book reflects Johns life against Lens and invites its reader to consider the effects of that influence, for good and ill, as it contributed to making John Williams the supremely accomplished, complex and compassionate person he was to become. Can any of Johns great achievements be attributed to his reaction to the ambition his father had for him from early childhood?

Concerned primarily as it is with the man and his making, this work has no intention of providing an exhaustive concert-by-concert, recording-by-recording account of John Williamss musical career, a worthy aim but one that can wait for now. Rather, it tells of the life and development of a fascinating man who happens to be one of the most important musicians of his time.

William Starling

Suffolk

September 2012

I n the course of research for this book I have had the pleasure and privilege of meeting and interviewing members of John Williamss family and a great number of his friends and musical associates. Almost without exception, they expressed their amazement that John had finally sanctioned the writing of his biography; they had believed it would simply never come to pass. The idea of the book was conceived over a post-concert dinner on the terrace of a restaurant on the Rhine in Cologne. It was a balmy September evening and John Williams and John Etheridge were relaxing after their enthusiastically received performance at the citys superb Philharmonie concert hall. I lived with my family in Cologne for most of the nineties and, with my wife, Eila, I went to celebrate her birthday and to watch our friends in action at the venue where we had enjoyed so many great concerts. Eilas day was made when the Johns dedicated their encore number to her and the icing on the cake came when John Williams gallantly presented his platform bouquet to her after the show.

The two Johns are always great company and were in that special afterglow that makes musicians such great company after a successful gig. We enjoyed badly pronounced but beautifully cooked German food, taking our time over the small glasses of Klsch, the excellent local beer. The conversation meandered pleasantly alighting on a variety of random topics but always gently veering away from anything in danger of becoming too serious. As the sun dipped and the cabbages and kings began to wane, John Etheridge posed a regular question of me, When are you going to write my life story? He was not expecting a sensible answer since this was a standing joke between us born of my having written odd biographical pieces for him combined with his desire for even more immortality than his formidable musical legacy will provide. The question was laughed off, as ever, but it prompted me to ask John Williams why he had never been the subject of a biography. I received the answer that I think I was expecting. Paradoxically, one of the most widely known things about John Williams is that he is a very private person. Despite his fame, worldwide following and incredible career, he eschews celebrity and is utterly devoid of any sense of showbiz or self-promotion. Certainly, he is aware of his standing as a musician and of his role in modern music but his answer was that it would never happen.

I respected his position of course but, as we returned to England, I became more and more fixated on the idea, so just before we left the country again for a long-planned holiday, I wrote to John making a case for the biography and for me as its author. Beyond swearing that blackmail or threats of violence never came into it and there was very little in the way of coercion or duress, I shall not reveal exactly how I persuaded him. Suffice to say that the letter did the trick. John called me when I returned from my holiday, inviting me to lunch to discuss the matter further and, to my amazement, agreed not just to the notion of the book but also to co-operating with me as its author. Having done so, he embraced the idea with his characteristic, wholehearted enthusiasm. He made clear that, while he would co-operate fully, giving me interview time, access to his papers and introductions to his friends, it was totally my project. This was welcome news since I feared there was a chance that perhaps his agreement would come with the cloying condition of editorial control. As I have grown to know John better I realise what an absurd concern that was.