Acknowledgments

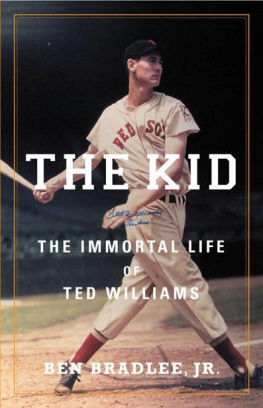

A cknowledgments, in the case of so personal a recollection of a friendship, might not seem entirely appropriate, but I wouldnt be comfortable passing up the chance to credit Neil Amdur, one of The New York Times favored editors. To find out why, youll have to read the book; I wouldnt want to spoil the beginning. And since that gets me in the mood, I am inclined as well to openly appreciate all those years of having as my editors at Sports Illustrated such Time Inc. giants as Andre Laguerre, Roy Terrell, Ray Cave, and Gilbert Rogin, who, during those times, not only put up with me but encouraged my entreaties to go here and there and do this and that for publication with the likes of Ted Williams, even when it meant going to the unlikeliest of places halfway around the world. They undoubtedly understood sooner than I why this was a good thing. And, of course, theres now one more to thank, Tom Bast of Triumph Books, who came to me quite unexpectedly, picked up this particular ball, and ran with it.

1. Its Only Me

Loss is measured most accurately by the void that it leaves. The breadth of it sometimes catches us unawares. The day after Ted Williams died, Neil Amdur of the New York Times called to ask if Id write a reminiscence on my experiences with Ted; he said he wanted it for the Sunday editions. Through Neils aegis, I had become an irregular contributor to the Times over the years and enjoyed the relationship, but on this occasion, on fielding his call, I found myself more boggled than beguiled. To be sure, I could appreciate from long exposure the stratum Williams reputation had reached, the almost mythic figure he cut as an American icon who transcended sport and movedor so it seemedbeyond the customary constraints. In that context, I might have even numbered myself among those who werent sure Ted Williams could die.

But in fact, I knew him much differently than that and in much more earthly terms, and in the den at home that serves as my office in Miami, Neil Amdurs call roused me from the refuge I had allowed myself to take from the news. I suddenly realized I had not confronted the void it would leave. I know when our defenses kick in we mortals tend to cope with that final inevitability as superficially as possible; we commiserate and move on (Joe Smith died last night... how sad... pass the salt). It doesnt make us any less human, its just the way we are. Now, however, alone in the den but tethered to the call, I was struck in the saddest possible way that a part of my life that I had too often taken for granted had been closed off except to memory.

And at that moment, as if by direction, my eyes fixed on a sliver of black wood standing in a corner of the room between elongated items unsuited for the walls (an African ceremonial spear, a jai-alai cesta, etc.). The office exudes an indifference to order that all but blends out the varied memorabilia that serve as decoration, and it had been a very long time since I zeroed in on any of it. But now the black wood focused into shape and I got a chill up my spine that was palpable. It was the baseball bat Ted have given mehow long ago? Twenty-five years?that I knew he valued greatly because it commemorated, with the dates etched in gold around the barrel, his 18 appearances in Major League All-Star Games.

And then, as if insinuated into one of those Hitchcockian movie scenes (exaggerated by clashing cymbals) where the protagonist suddenly realizes hes in the middle of a discovery, my minds eye locked onto other sharpened images: a picture of Ted and me talking on the field in Washington when he managed the Senators; cover renderings of two of the three books we had done together for Simon & Schuster; and after the first, My Turn at Bat , had made the bestseller lists, a picture of Bing Crosby and Joe Garagiola holding it open and smiling broadly, as if theyd found a portion only they could fathom.

And without seeing it, but yet seeing it better than ever, the large dark head and sweeping horns of the sable antelope that looms from the wall in the family room, a trophy I had brought down on safari when Ted and I went to Zambia together. And in another part of the house, the handgun he insisted I borrow because I didnt have one for general protective purposes, as he put it, and then refused to take back. And somewhat gloomily, the rods and reels he had pushed on me to facilitate my becoming more than just another average fisherman, now mostly out of commission and rusting away in the tool shed.

And in the side yard, a boat, too. A 13-foot Gamefisher that he once endorsed for Sears & Roebuck that I wouldnt let him give me, but that Id bought at his suggestion for my oldest son, John, to use, and that my teenager, Josh, had recently put back on active duty. The last time we saw Ted, Josh reminded him of the boat and how much he enjoyed using it to ply the shallower waters around South Florida. Ted said he damn well better be using it, that being what boats are for, and that he should let your father drive it occasionally, too, because he probably needs the practice.

And I thought, too, of all those other heirlooms that I had squirreled away without thinking of them as such: the baseballs he had signed and sent unsolicited to my children; the bric-a-brac from the outdoor adventures we shared on three continents; the letter he had written after my attempt at interpreting for Sports Illustrated our first stab at fishing together, flattering me for capturing the real Ted (a tacit acknowledgment that there were many public Teds that werent real). And the tapes. Oh, my, the tapes. In the den closet, in a crusted cardboard box long ignored, the hours and hours of conversationcandid, stark, joyous, sad, anguished, profane, triumphant, revealingthat wed recorded over the years, in places hither and yon, in the way of evaluating a unique persona and a life that had fairly bristled with colossal ups and abysmal downs.

And like a forced accounting, the sum of all that made me realize how much I had come to love the man, even as one might a favored older brotheror perhaps more appropriately in Teds case, a cherished but wonderfully eccentric uncle. And how I had come to understand how misrepresented he had been in so many ways (and how bruisingly accurate in others, even when he couldnt see it himself), and how much I was going to miss him, even though our contacts had been reduced to the occasional in recent years and all but petered out when he moved upstate and got so sick.

I dont pretend, now or at any time, to have been closer to Ted Williams than anyone else. Not at all. Im not sure Id have wanted to be. I knew him a long time, but others certainly knew him longer. If I numbered myself among his good friends, I would also concede that he had a lot of those, moving around him like pilot ships in a crowded harbor. But that was always a pretty volatile anchorage; a number of the more obvious ones had eventually dropped out, sometimes traumaticallyand sometimes because, quite frankly, Ted Williams didnt always treat friends the way friends ought to be treated. Besides, we were an unlikely pairing. I was, after all, a writer, among a subculture he routinely disparaged, and was relatively late coming into his life, being a generation younger. We traveled mostly in different orbits. But we connected, for reasons I now see as obvious.

We had met years before when he was near the end of his career and I was just beginning mine, on scholarship at the University of Miami and writing for the Miami Herald . I was on assignment at a horse show on Dinner Key where he sat alone in a front-row box, and the shows hostess insisted on taking me over to say hello. I was not eager, having heard and read of his active antagonism toward what he called the knights of the keyboard. But I went anyway, and instead of a rebuff, got an invitation to join him in the box.

Next page