then has the shape of life grown old...

The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk.

Introduction

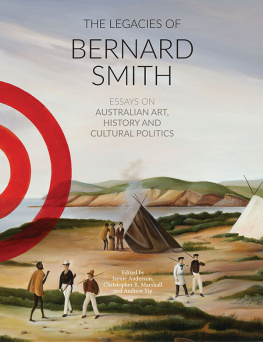

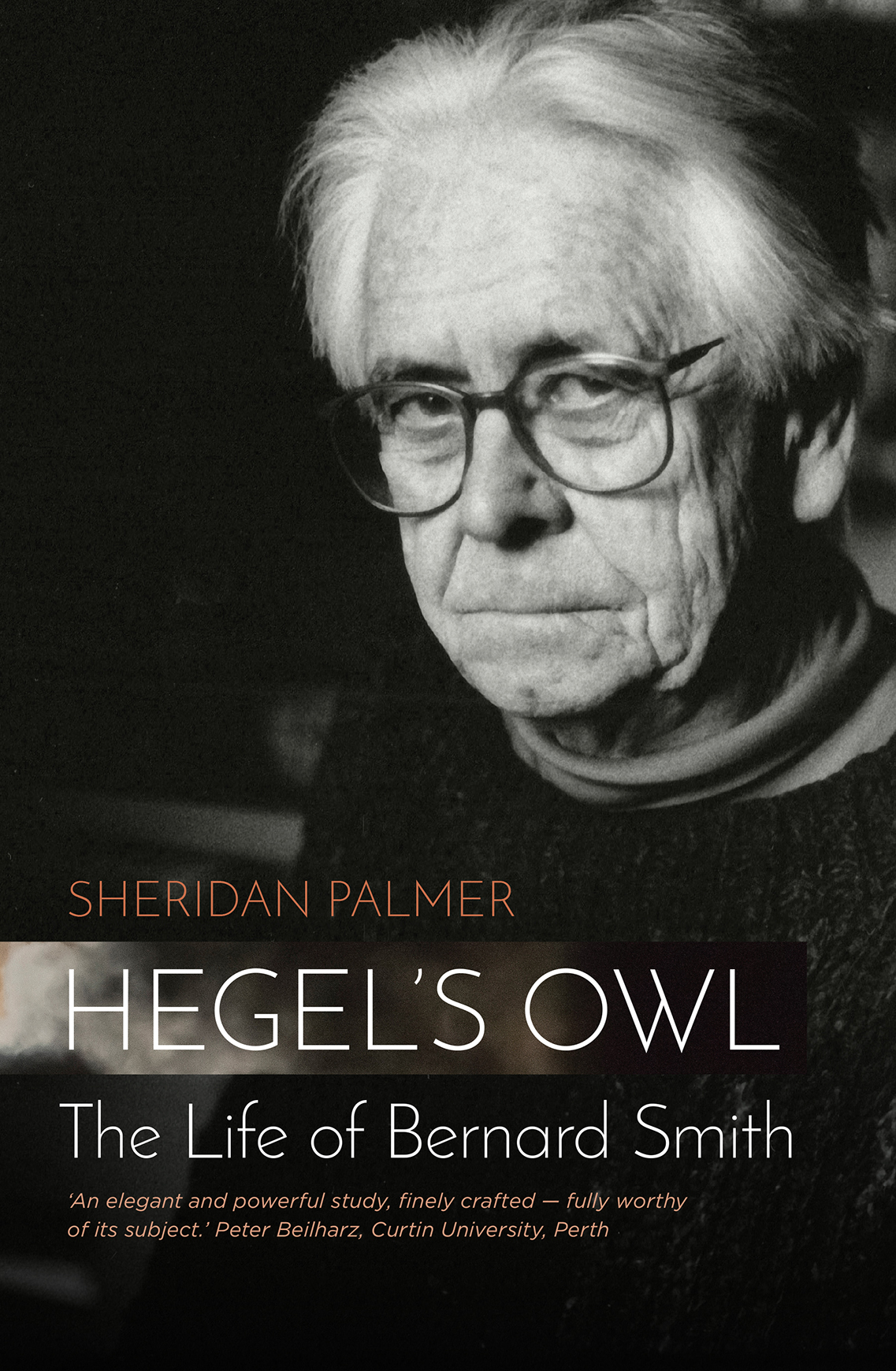

Biographies of major intellectuals are ways of re-examining cultural landscapes, political entanglements and national histories. When a figure such as Australias great art historian Bernard Smith (19162011) comes under the biographers lens, an immense interdisciplinary world opens up, revealing a convergence of challenging relationships, compelling images and a man endowed with unwavering determination. To condense such a life requires an intricate understanding of the time and place in which he grew up and maturedinterwar and postwar Australiaand the impact of tumultuous world events, but equally how his uncommon childhood, illegitimacy and identity as a ward of the State shaped him. From these he formed a complex relationship with society and an incisive vision of cultural inheritance. Always interested in the big picture and how it served in defining Australia, Bernard Smith questioned and wrote from a fiercely antipodean viewpoint. His epic revision of Australias modern cultural position and his theories of contact, exchange and identity, together with his ability to steer a critical course through vast historical terrains, mark him as one of Australias most brilliant and pioneering intellectuals.

I came to know Bernard Smith late in his life, late enough to glimpse the hardened shell of a triumphant but battle-worn man, not unlike one of the old leather volumes in his well organised library. That library, collected over seventy-five years, filled more than four rooms with books that measured and marked his intellectual journey, and contained his favourite authors and apostles of knowledgeDarwin, Caudwell, Eliot, Forster, Hegel, Jack Lindsay, Marx, Poe, Toynbee, Vico, and the postmodernists Foster, Derrida, Bhabha, Bourdieu, Hassan, Rose, Said and Levinas. These book-ended his large trove of monographs and studies on Australian art and artists, from European settlement to his present.

I recall in particular one warm summers evening in 2005 when Bernard and I independently emerged from a crowded exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, he inquiringBernard liked inquiringwhether I would walk with him to the tram. He would have been in his late eighties, but cut a distinguished figure with his long white hair, handsome in his cream linen suit. There was a virile quality to his easy, gentleman-like charm and conversation, and that short stroll to Flinders Street station and he to his tram, left a lingering impression of an old lion who had fought many intellectual battles and lived a fulfilling lifeone that merited the title the father of Australian art history. He had, after all, worked hard for success; it had not been handed to him nor had he inherited it, but he had been lucky, as he used to say. There was, however, a sense that he was not yet ready to fly off into the dusk of literary or scholastic oblivion.

When Bernard invited me to write his biography I felt much as Oskar Spate did when Sir Keith Hancock suggested he write a new Australia ; he was extremely flatteredtoo flattered to decline. But like Spate, I was extremely anxious about such a massive task. Smiths reputation as a colossus in the world of art and cultural history, both antipodean and international, was without peer in Australia, and I knew that writing the life story of this man would be a weighty challenge.

A biography isnt a poem, it isnt a novel, its a document, but in some ways Bernard Smiths life was all three genres. He had written major historical works, biographies and autobiographies, had published his poems and criticisms, and left an archive of thousands of documents. So thoroughly visible had he left all his tracks, perhaps too visible for comfort, that the most gruelling aspect of this project was to find the hidden seams of his life, the secret closet of his mind and past. It therefore seemed sensible to work backwards until I found the origins of Smiths first moment of visibility; that, for a bastard boy, was not easy. Illegitimacy has a way of cloaking a child; and he was for the most part a filius nullius , but even there Bernard had been lucky and had escaped the usual destination of fostered children, many of whom were sent to farms that operated like nineteenth-century workhouses. Instead, he became a favoured ward in what was called a farming-out house, the winsome child who flourished as best he could under the circumstances set by the State Welfare Department of New South Wales.

An exceptional life is determined by many factors and it cannot be entered by means of one key. He also held to the Hegelian notion that you cannot re-create the past, but only understand it.

Born with an innate sense of his boundary, imposed by his illegitimacy and state-ward rearing, the foundation to Bernards character was determined by a deeply formed resilienceto society and to others, but not to himself. Ihab Hassan has written that it is ones sense of origins [that] haunts the critical mind and Bernard Smith must be read in these terms. In an essay written in 1956 on Coleridges The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1834), Bernard emphasised the importance of the feelings of childhood carried on into the powers of manhood, an admission or perhaps a glimpse into his own protected territory and primal hinterland. What is important is how he positioned himself in relation to everybody else and everywhere else.

For Bernard Smith words and the intellect were used to atone for the guilt of the fleshthat of his mother and fatherand his own. Later he transferred his reliance on words for interrogating invasion, conquest, morality, dispossession, Indigenous genocide and national consciousness, and defining antipodeanism and modernism. Unlike many state wards, Bernard experienced less ostracism due to the firm but affectionate family who fostered him. Nevertheless, his status as an institutional child made him develop an emotional distance, both from the polity and those who wielded power, and it instilled in him a Machiavellian attitude to the present and a preference for the past. Having inhabited a peripheral or decentralised position for the first part of his life, he grew to prefer marginality; it provided an objectivity that drove him to interrogate the centres and their fringes. As he matured and groomed himself on the seductive and coercive structures of Marx and Hegel, and the great art historians Winkelmann, Burckhardt, Gombrich and Pevsner, he gained the confidence to stride across cultural landscapes, whether colonial, postcolonial or his own modern antipodean world.

Robin Winks has suggested that a scholars subject matter or academic discipline usually holds an autobiographical meaning, in that one is often attracted to a discipline that appears to reflect the world as one understands it, rather than using the discipline to order the world. It is important, therefore, to ask how he tracked and deciphered the cultural shifts associated with imperial colonisation, elitism, socialism, romanticism, and modernism, and established a cultural genealogy, a program of origins, traditions and transfigurations that situated Australias cultural developments within the global and local conditions that had produced them.

Bernard wrote two memoirs covering the first half of his life. They reveal an obligation to truth, but memory is selective and, though he possessed an acutely sensitive and synthesising one, he wisely relied on contextual proof. A vigilant diarist who understood the importance of documenting events, he also used the diaries of others, for within such intimate documents are key emotions and the psychological knife. With those sources and his encyclopedic filing system where place, date and circumstantial evidence about those who mattered were recorded, Bernard validated his well-charted life. According to one colleague, he knew only too well that if one is being transformed into a myth in ones lifetime, it is sensible to take a hand in the process.