All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any process electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW Press. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials.

Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

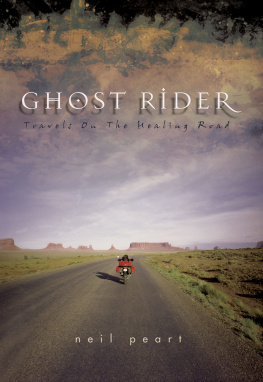

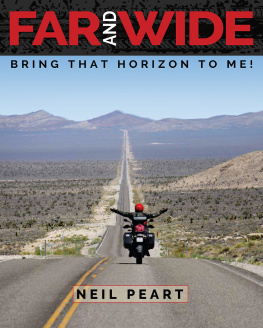

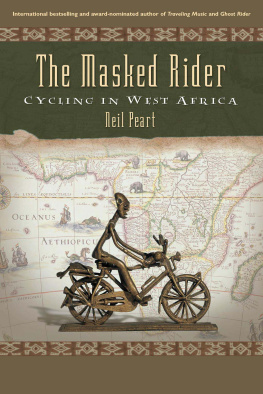

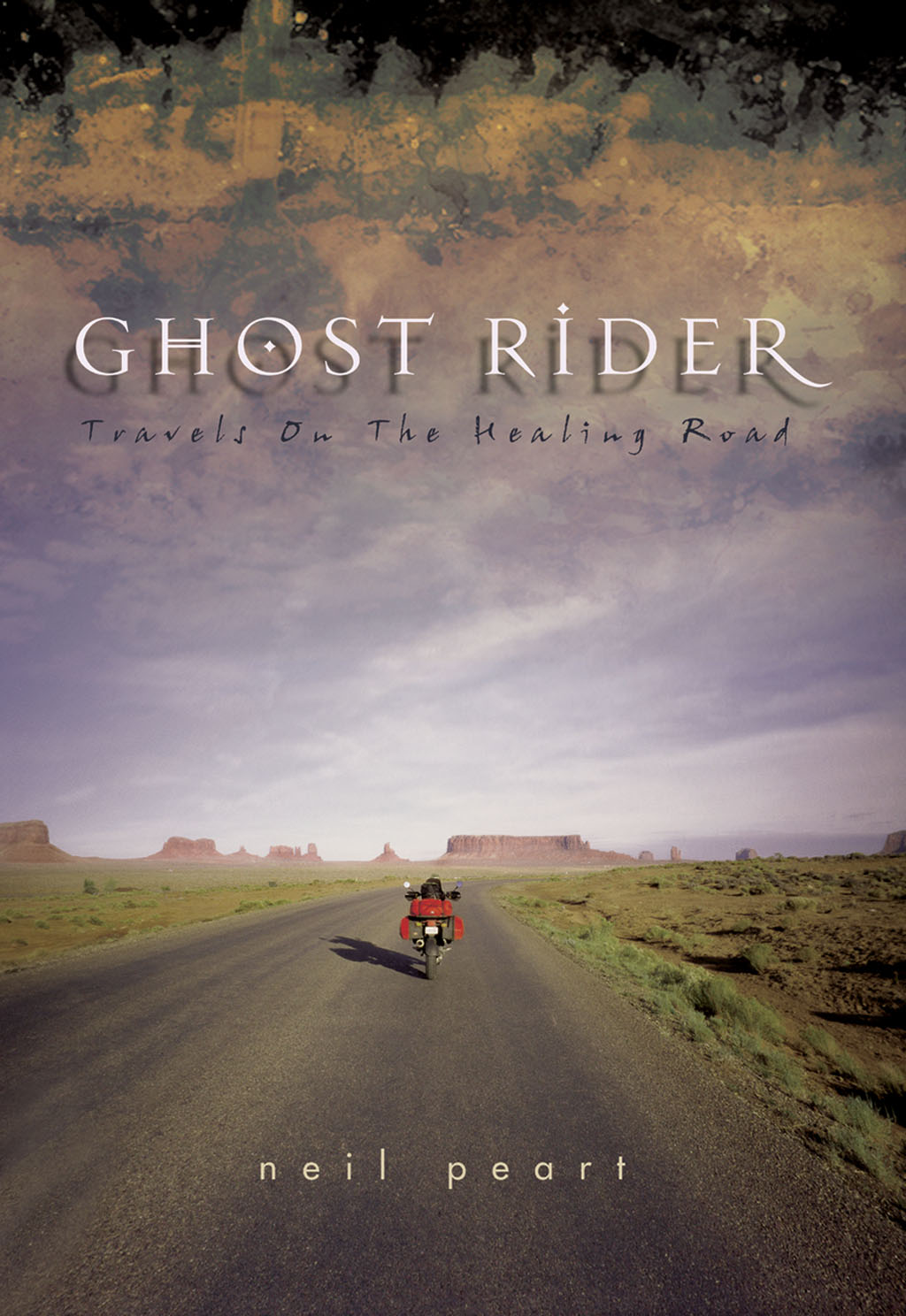

1. Peart, Neil Journeys North America. 2. North America Description and travel. 3. Motorcycling North America. i. Title.

except pages and which are by Brad French.

Chapter 1

INTO EXILE

You can go out, you can take a ride

And when you get out on your own

You get all smoothed out inside

And its good to be alone

FACE UP, 1991

Outside the house by the lake the heavy rain seemed to hold down the darkness, grudging the slow fade from black, to blue, to gray. As I prepared that last breakfast at home, squeezing the oranges, boiling the eggs, smelling the toast and coffee, I looked out the kitchen window at the dim Quebec woods gradually coming into focus. Near the end of a wet summer, the spruce, birch, poplars, and cedars were densely green, glossy and dripping.

For this momentous departure I had hoped for a better omen than this cold, dark, rainy morning, but it did have a certain pathetic fallacy, a sympathy with my interior weather. In any case, the weather didnt matter; I was going. I still didnt know where (Alaska? Mexico? Patagonia?), or for how long (two months? four months? a year?), but I knew I had to go. My life depended on it.

Sipping the last cup of coffee, I wrestled into my leathers, pulled on my boots, then rinsed the cup in the sink and picked up the red helmet. I pushed it down over the thin balaclava, tightened the plastic rainsuit around my neck, and pulled on my thick waterproof gloves. I knew this was going to be a cold, wet ride, and if my brain wasnt ready for it, at least my body would be prepared. That much I could manage.

The house on the lake had been my sanctuary, the only place I still loved, the only thing I had left, and I was tearing myself away from it unwillingly, but desperately. I didnt expect to be back for a while, and one dark corner of my mind feared that I might never get back home again. This would be a perilous journey, and it might end badly. By this point in my life I knew that bad things could happen, even to me.

I had no definite plans, just a vague notion to head north along the Ottawa River, then turn west, maybe across Canada to Vancouver to visit my brother Danny and his family. Or, I might head northwest through the Yukon and Northwest Territories to Alaska, where I had never travelled, then catch the ferry down the coast of British Columbia toward Vancouver. Knowing that ferry would be booked up long in advance, it was the one reservation I had dared to make, and as I prepared to set out on that dark, rainy morning of August th, 1998 , I had two and a half weeks to get to Haines, Alaska all the while knowing that it didnt really matter, to me or anyone else, if I kept that reservation.

Out in the driveway, the red motorcycle sat on its centerstand, beaded with raindrops and gleaming from my careful preparation. The motor was warming on fast idle, a plume of white vapor jetting out behind, its steady hum muffled by my earplugs and helmet.

I locked the door without looking back. Standing by the bike, I checked the load one more time, adjusting the rain covers and shock cords. The proverbial deep breath gave me the illusion of commitment, to the day and to the journey, and I put my left boot onto the footpeg, swung my right leg high over the heavily laden bike, and settled into the familiar saddle.

My well-travelled BMW R1100GS (the adventure-touring model) was packed with everything I might need for a trip of unknown duration, to unknown destinations. Two hard-shell luggage cases flanked the rear wheel, while behind the saddle I had stacked a duffel bag, tent, sleeping bag, inflatable foam pad, groundsheet, tool kit, and a small red plastic gas can. I wanted to be prepared for anything, anywhere.

Because I sometimes liked to travel faster than the posted speed limits, especially on the wide open roads of the west where it was safe in terms of visible risks, but dangerous in terms of hidden enforcement I had decided to try using a small radar detector, which I tucked into my jacket pocket, with its earpiece inside the helmet.

A few other necessities, additional tools, and my little beltpack filled the tankbag in front of me, and a roadmap faced up from a clear plastic cover on top. The rest of the baggage I would carry away with me that morning had less bulk, but more weight the invisible burdens that had driven me to depart into what already seemed like a kind of exile.

But at that moment, before Id turned a wheel or even pushed off the centerstand, I reaped the first reward of this journey, when my thoughts and energies contracted and narrowed their focus to riding the machine. My right hand gently rolled on the throttle a little more, left hand wiped away the raindrops already collecting on my clear faceshield, then pulled in the clutch lever. My left foot toed the shifter down into first gear, and I moved slowly up the lane between the wet trees. At the top I paused to lock the gate behind me, wiped off my faceshield again, and rode out onto the muddy gravel road, away from all that.

Just over a year before that morning, on the night of August , 1997 , a police car had driven down that same driveway to bring us news of the first tragedy. That morning my wife Jackie and I had kissed and hugged our nineteen-year-old daughter, Selena, as she set out to drive back to Toronto, ready to start university that September. As night came on, the hour passed when we should have heard from her, and Jackie became increasingly worried. An incorrigible optimist (back then, at least), I still didnt believe in the possibility of anything bad happening to Selena, or to any of us, and I was sure it was just teenage thoughtlessness. She would call; thered be some excuse.