Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

Text and photographs copyright 2016 by Bill Porter

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Porter, Bill, 1943

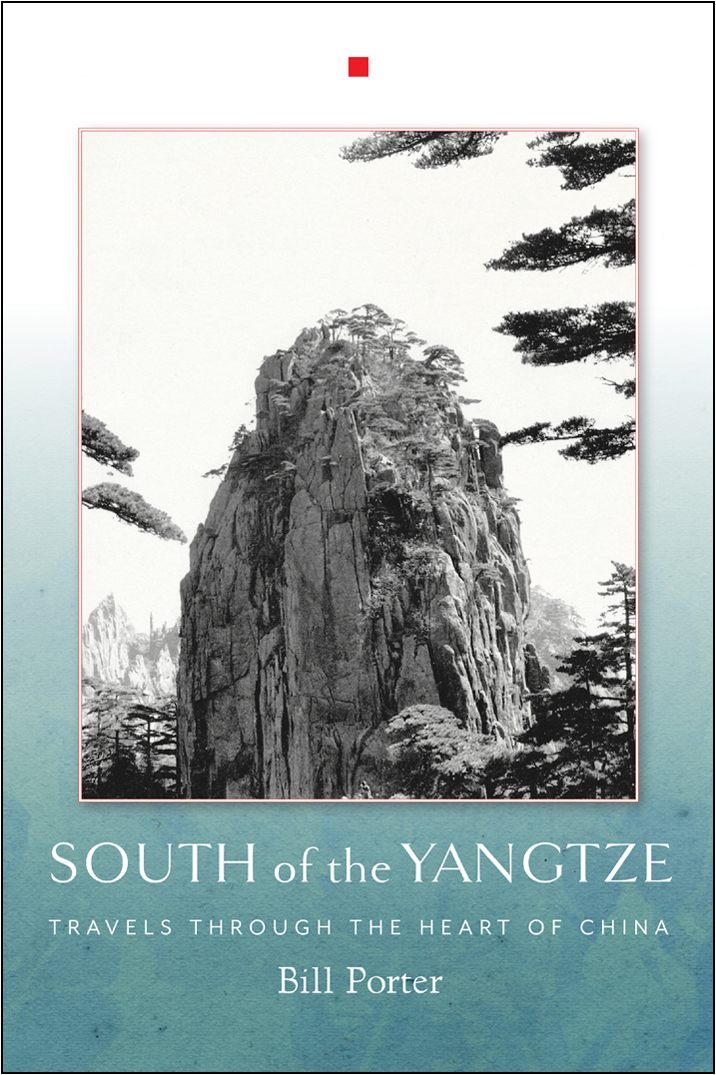

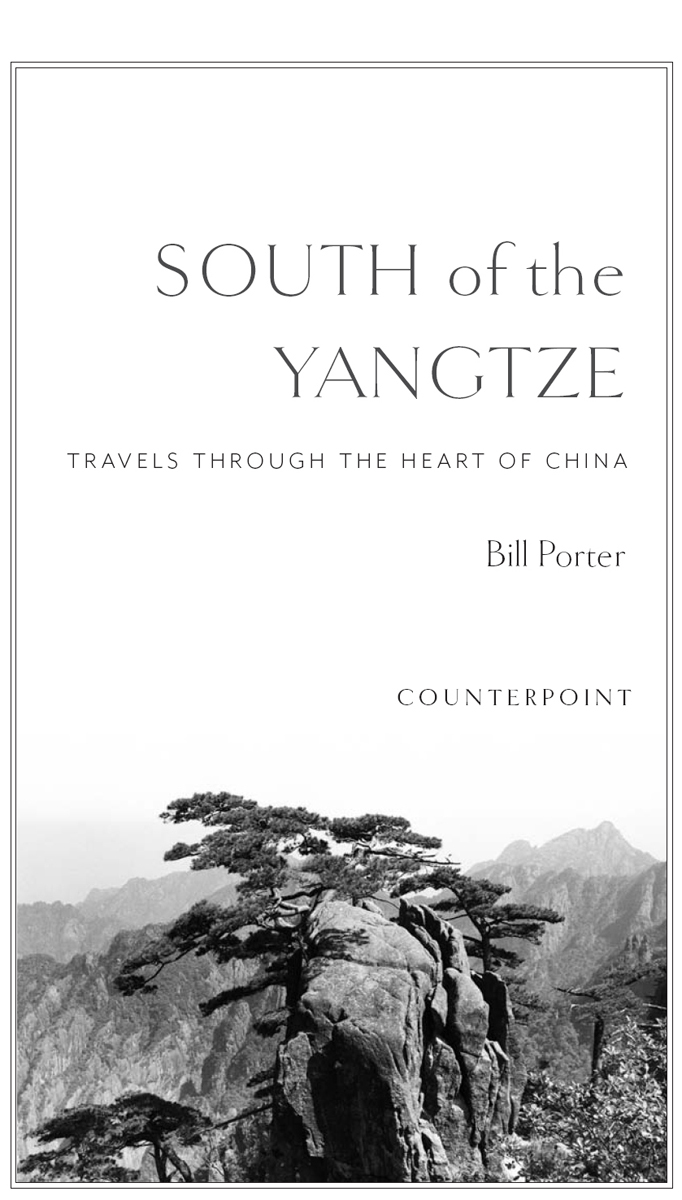

Title: South of the Yangtze: travels through the heart of China / Bill Porter.

Description: Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2016008978

Subjects: LCSH: Yangtze River Region (China)--Description and travel. | Porter, Bill, 1943---Travel--China--Yangtze River Region. | Landscapes--China--Yangtze River Region. | Yangtze River Region (China)--History, Local. | Yangtze River Region (China)--Social life and customs. | Yangtze River Region (China)--Pictorial works. | Black-and-white photography--China--Yangtze River Region. | BISAC: TRAVEL / Asia / China.

Classification: LCC DS793.Y3 P67 2016 | DDC 951.2--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016008978

Cover and interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

Typesetting by Tabitha Lahr

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

e-book isbn 9781619028845

To Melanie Nan and Nic Gould

I f you look at a map of China, you cant help but notice that the country is dominated by two riverstwo rivers that wander more than 5,000 kilometers, from west to east, and from the roof of the world to the sea. The river that drains North China is the Yellow River, the Huangho, while the river that drains Central China is the Long River, or Changchiang, better known in the West as the Yangtze. I suppose we could also add the West River, which drains South China. But South China has not played much of a role in the development of Chinese civilization until very recently.

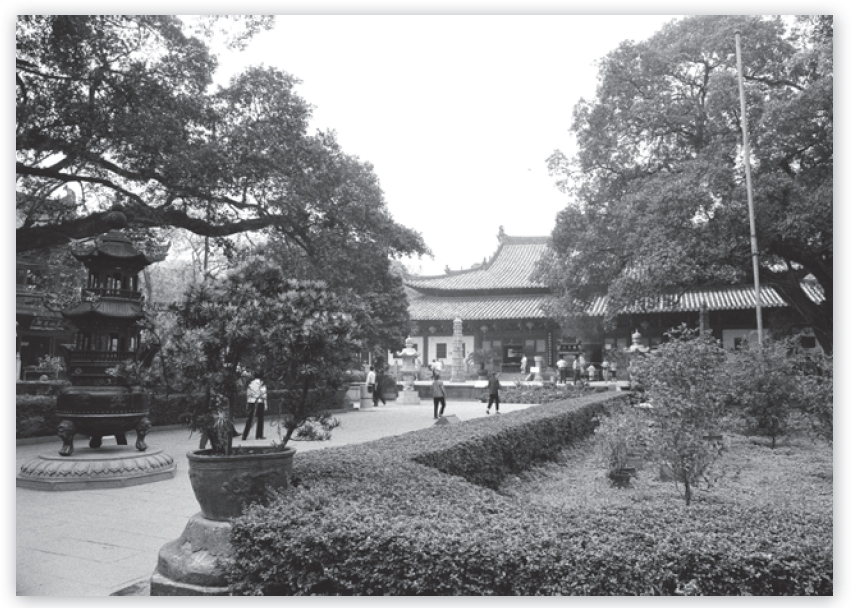

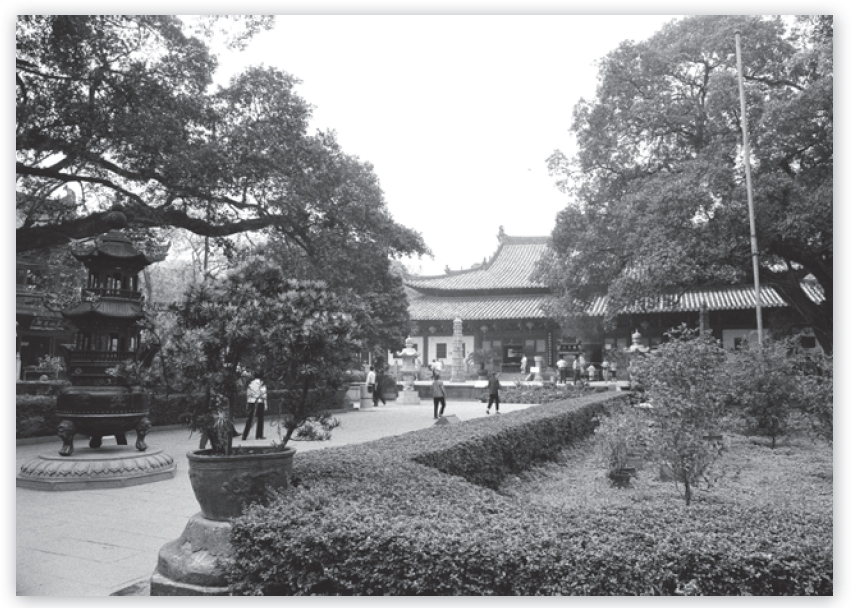

Kuanghsiao Temple and mind-flapping flagpole

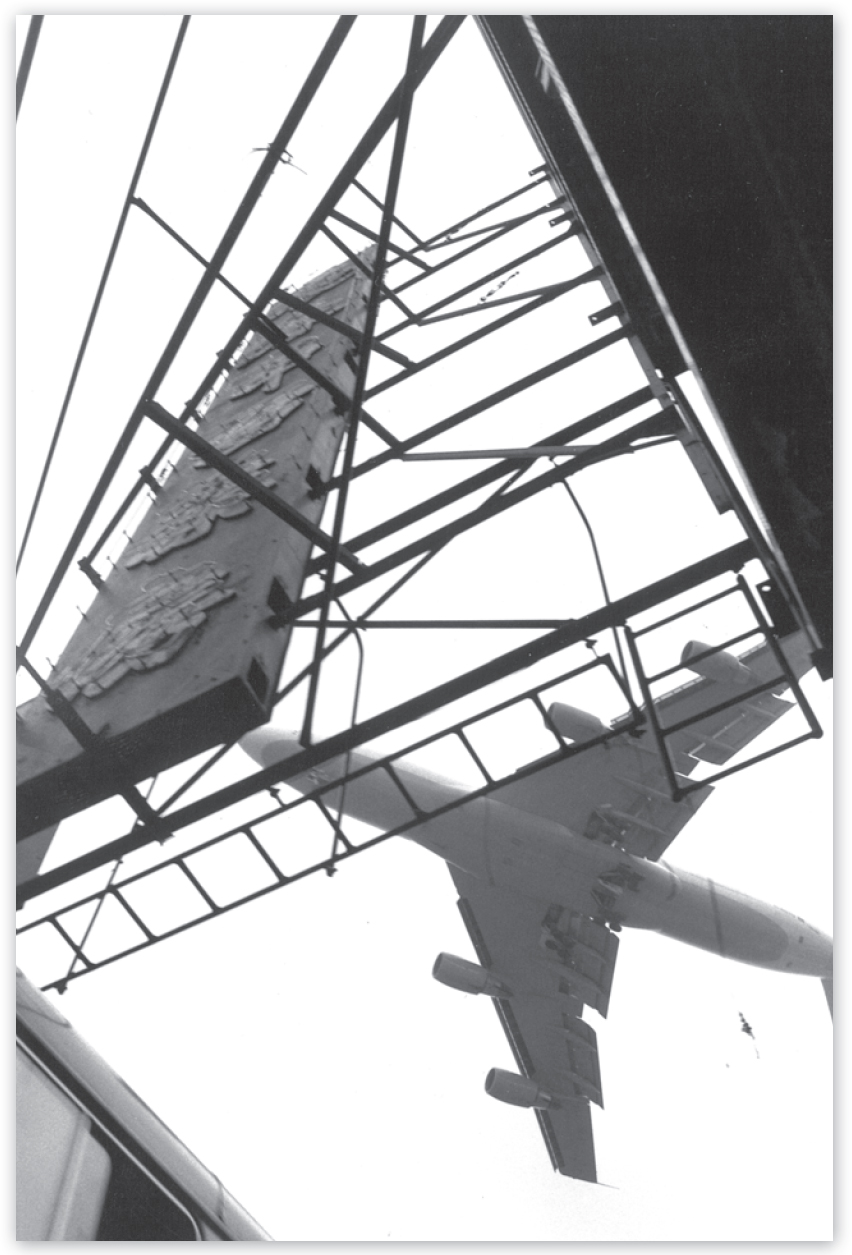

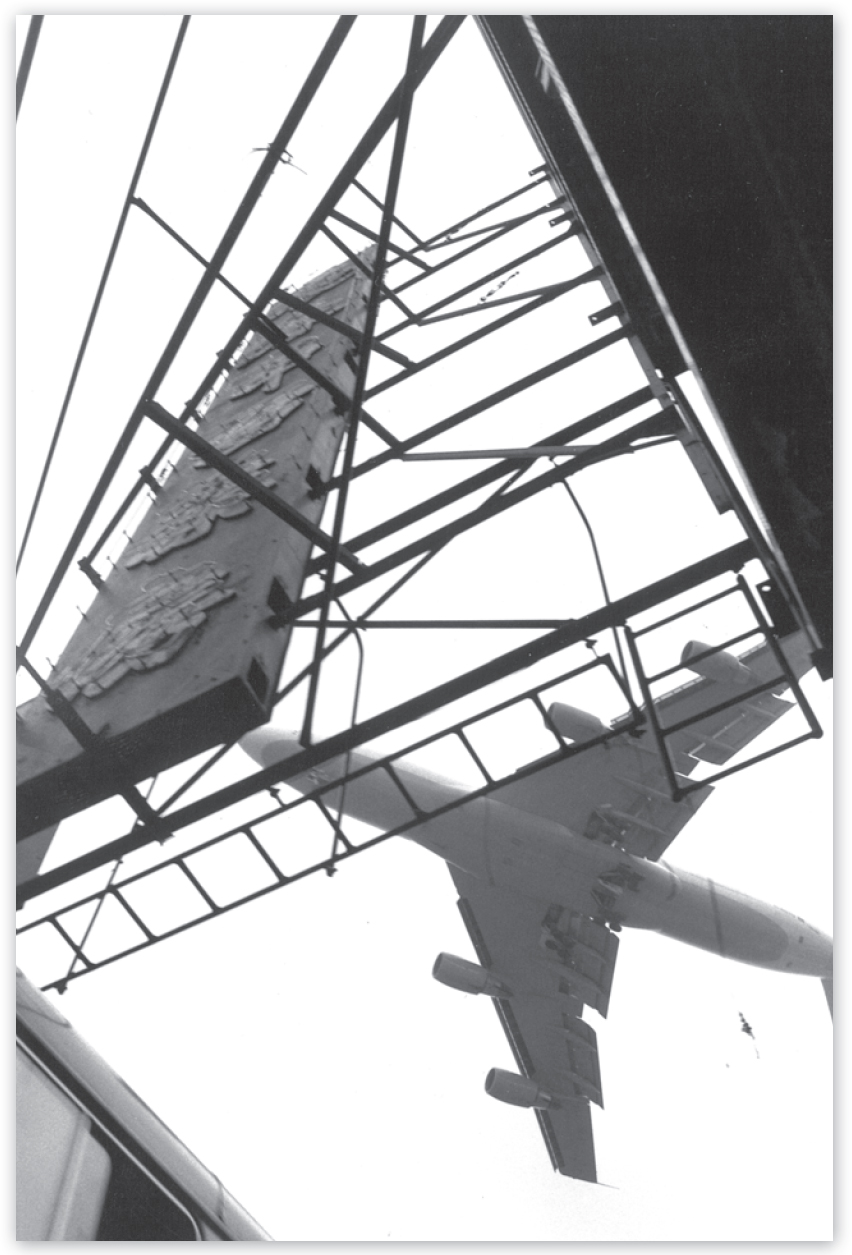

Steve and Finns plane landing at Kai Tak

Chinese civilization first developed 5,000 years ago in North China along the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, and that remained its center for the next 4,000 years. Then a thousand years ago, this changed. A thousand years ago, as a result of invasions from the north, the center of Chinese civilization moved south to the Yangtze. Several centuries later, the Chinese recaptured the North and once more established their capital there. But the Yangtze, not the Yellow River, has remained the center of its civilization ever since.

A thousand years ago, the Chinese came up with a name for this region. They called it Chiangnan, South of the River, the river in question, of course, being the Yangtze. The Chinese still call it Chiangnan. Nowadays it includes the northern parts of Chekiang, Kiangsi, and Hunan provinces and the southern parts of Anhui and Kiangsu. But its not just a region on the map. Its a region in the Chinese spirit. And if you ask a dozen Chinese what Chiangnan means, theyll give you a dozen answers. For some, the word conjures forests of pine and bamboo. For others, hillsides of tea, terraces of rice, or lakes of lotuses and fish. Or they imagine Zen monasteries, Taoist temples, artfully-constructed gardens, or mist-shrouded peaks. Oddly enough, no one I have asked has ever mentioned the regions cities, which include some of the largest in the world. Somehow, whatever else it might mean to the Chinese, Chiangnan means a landscape and a culture defined by mist, a landscape and a culture that lacks the harder edges of the arid, ever-embattled North.

In the fall of 1991, I decided to travel through Chiangnan, following the old post roads that still connect its administrative centers and scenic wonders. I was in Hong Kong at the time, and being a foreigner, I needed a visa. This was always easy to arrange. China was next door. A visa could take as little as a day.

Once I had my visa, it was time to pack. I got out the old Forest Service backpack I had acquired in the summer of 1977 while trying to recover from hepatitis with a regimen of physical labor. I tossed in a couple changes of clothes, including a jacket for the rainthe Yangtze, after all, carries more water than any other river in the world, and that water has to come from somewhere and fall on someone. I also added a camera to record the sights I hoped to see, and a journal to record the insights I hoped to be blessed with, and a set of prayer beads for the buses, and enough money to last six weeks. I figured the trip I had in mind would cost $1500a modest amount, as I would be sharing hotel rooms and meals with my friends Finn Wilcox and Steve Johnson.

A couple years earlier, Finn and Steve published a book together called Here Among the Sacrificed about the fine life of riding freight trains in America. Finn was a poet, and Steve was a photographernot that either of them made a living doing either. Poems and photos were what they were good at. Both had to find other ways of making a living. Finn worked as a tree planter and landscape gardener. Steve worked in a boatyard repairing sailboats and fishing trawlers.

I watched their plane arrive at Kai Tak Airport. Kai Tak landings were always exciting. Whenever pilots made that final turn as they straightened out short of the runway, passengers could look just beyond the wingtips into apartment buildings and see people playing mahjong or watching TV. It was exhilarating. When Finn and Steve came through customs, they were still talking about the landing and glad to be alive. I smiled and welcomed them to Hong Kong.

Since they had already arranged their China visas in America, there was no need to linger. We headed for the train station. It was late September, but fall had yet to show up. The temperature was in the nineties. Fortunately, the express train we boarded in Hong Kong was air conditioned. It would be the last air-conditioning we would enjoy for quite a while.

The train was the express to Kuangchou. Once it left, it didnt stop until it got there. This was 1991, and the border town of Shenchen was simply that, just a border town. As we entered China, there was a big billboard with a smiling picture of Teng Hsiao-ping telling us that change was on the way. If it was, it hadnt reached Shenchen. At least, not yet. A few minutes later, we entered a landscape of rice fields and duck ponds and farmers dressed in black wearing broad-brimmed hats of woven bamboo. Variations of this scene continued for two hours, until the factories began to appear, and finally the high-rise apartment buildings. Two and a half hours after leaving Hong Kong, we arrived in Kuangchou. We slipped through immigration and customs so fast we felt like diplomats.