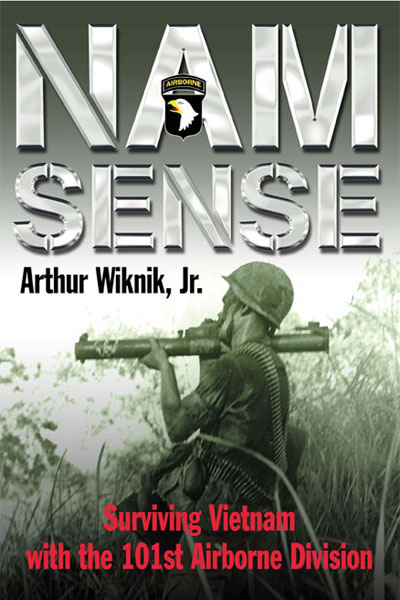

Published in the United States of America in 2009 by CASEMATE

1016 Warrior Road, Drexel Hill, PA 19026

and in the United Kingdom by CASEMATE

17 Cheap Street, Newbury, Berkshire, RG14 5DD

Copyright 2005 by Arthur Wiknik, Jr.

ISBN 978-1-935149-09-5

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress and from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Printed and Bound in the United States of America

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact

United States of America

Casemate Publishers

Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146

E-mail casemate@casematepublishing.com

Website www.casematepublishing.com

United Kingdom

Casemate-UK

Telephone (01635) 231091, Fax (01635) 41619

E-mail casemate-uk@casematepublishing.co.uk

Website www.casematepublishing.co.uk

To the families and friends of the 58,209 men and women who sacrificed their all in Vietnam;

To Tommy Shay, Jimmy Manning and Ray Contino, boys from my childhood who died in the war.

And to the thousands of men and women who so proudly and bravely served in the military during one of the most turbulent times in our nations history.

Maps and Illustrations

Youth is the first victim of war: the first fruit of peace. It takes twenty years or more of peace to make a man; it takes only twenty seconds of war to destroy him. Baudouin I

Preface

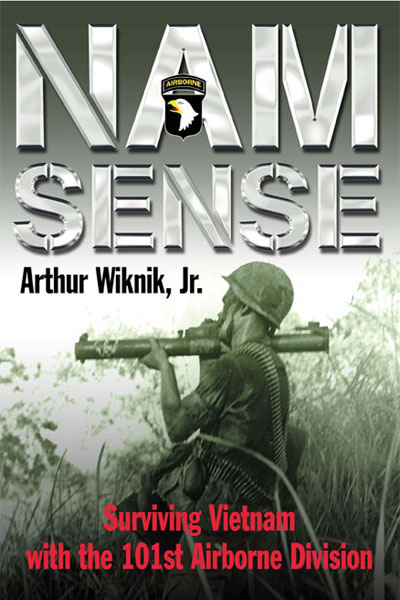

This story is about my life in 1969 and 1970 during the height of the Vietnam War. I wrote it to give you a sense of what the average GI endured during this turbulent time in our nations history. I think it also shows why most young men can go to war and return home without being haunted by their experiences for the rest of their lives, and why some cannot. Although many veterans and their families suffered in different ways, this book does not seek to discredit those killed, wounded, or psychologically affected by the war.

I was drafted into the US Army in 1968 and after extensive stateside training, was sent to Vietnam in 1969 as a non-commissioned officer and infantry squad leader. The military expected me to drop into the middle of the war and, without any experience whatsoever, lead men in combat. I was barely twenty years old. The last thing I wanted was to be fighting an enemy in his jungle on the other side of the world, but there I was, and I was determined to make the best of it. My extra stateside training, discipline, and will to survive instilled within me a resolute goal as a squad leader to finish my tour of duty and go home in one pieceand take as many of my men with me as possible. This usually put me at odds with gung-ho superiors who habitually put the mission ahead of the men.

And so my series of adventures and misadventures began in Vietnam, a country where the bizarre was often the norm. I tried as best I could during my year-long tour of duty to find the humorous side of daily life in Vietnam, where shooting and blowing up other human beings was what you were supposed to do. Finding humor and staying sane in the middle of a war is not an easy thing to do. My occasionally flippant attitude and desire to survive the experience did not always help mattersand certainly did not sit well with other officers, some of whom were utterly incompetent and dangerous in the field. As a result, I often found myself in outlandish situations, most of my own making.

In addition to trying to survive the war, soldiers had to deal with the unpopularity of the conflict at home, as well as the venom heaped upon us by the anti-war movement, which made it difficult to perform our duties to the fullest. Also, as in all wars, we were forced to endure the ever present specter of human death by gruesome means. Unlike how it is at home, in combat there are no wakes or funerals, and little or no time to grieve. When someone is killed or seriously wounded, we simply acknowledged it and soldiered on. To do anything else would exhibit weakness, something few soldiers were willing to portray.

Nam-Sense is not about heroism and glory, mental breakdowns, or haunting flashbacks; nor does it wallow in self-pity. As you will discover, the vast majority of GIs did not rape, torture, or burn villages. We were not strung out on drugs, and we did not enjoy killing. Although these unfortunate incidents did indeed occur during the war, as they do in every war ever fought, they were not on the grand scale we have been led to believe by people and organizations with different axes to grind. Brutality, violence, and offensive activities are the main ingredients of any war, but they were not the only ingredients of this war. Unfortunately, the medias negative and sensationalized reporting of isolated incidents not only made being a Vietnam veteran an embarrassment, but stereotyped us as well. This book responds to that unfair stereotyped image by revealing the level of courage, principle, kindness, and friendship demonstrated by most GIs. These are the same elements found in every other war Americans have proudly fought in.

This memoir was completed nearly thirty-five years after the fact, and so it was impossible for me to remember the exact name of every person who appears within these pages. A few of the names have been intentionally changed to protect familes, reputations, and memories.

Acknowledgements

As with every book ever written, there are many people to thank. Nam-Sense has been in development for the better part of three decades. During that time, many people have read bits and pieces of the evolving manuscript, offered their suggestions, and encouraged me to continue. Unfortunately, I cannot now remember everyone who played some role in assisting me. If I have overlooked your contribution to this book, please know it was inadvertent, and that I will forever be in your debt.

First, I would like to thank my Connecticut Local Draft Board #6 for selecting me above so many others for induction into the US military. Thanks are also due to the US Army for sending me to an exotic, dangerous land, riddled by war.

Dennis Silig and Howard Siner, two of the best friends a soldier could ask for, played an important role in my life. They helped to keep me alive and sane. Dennis passed away from cancer some years ago. I miss him.

Bruce Randall edited early versions of Nam-Sense and pushed me to keep writing; John Meehan came up with the clever Nam-Sense title.

I would also like to thank my publisher David Farnsworth, who directs Casemate Publishing, for believing in this project and accepting it for publication; and Theodore P. Ted Savas for rapidly and accurately getting the manuscript into publishable form.

Many people took the time to write letters to me in Vietnam when I needed them the most. I cant thank them enough.

My three daughters supported me along this long road, each in her own way. Sarah never tired of hearing my war stories; whenever I needed to talk, she was there to listen; Kimberly used her skills to prepare the photographs for Nam-sense (because her dad is a dinosaur when it comes to technology); when the computer was in her bedroom, Ashley never complainedeven when I typed away late into the night with the lights burning bright. My hope is that when each of you read this book you will better understand what so many endured for their country. I love you all, forever.

Next page