Australia

HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

http://www.harpercollins.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

2 Bloor Street East - 20th Floor

Toronto, ON, M4W, 1A8, Canada

http://www.harpercollins.ca

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers (New Zealand) Limited

P.O. Box 1

Auckland, New Zealand

http://www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

77-85 Fulham Palace Road

London, W6 8JB, UK

http://www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

10 East 53rd Street

New York, NY 10022

http://www.harpercollins.com

Nonfiction

Always Been There: Rosanne Cash, the List, and the Spirit of Southern Music

Voices of the Country: Interviews with Classic Country Performers

Johnny Cash: The Biography

Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison: The Making of a Masterpiece

Ring of Fire: The Johnny Cash Reader

CONTENTS

I just dont think that any of us thought we would spend ten years banging our heads against walls and not come out in good shape on the other side. If we had, I dont know if we would have had the spirit for it.

Dianne Davidson

THE LAST LIGHT of a November day in Nashville crept out of the room where Kris Kristofferson, in a black coat and scuffed boots, grappled with my questions. Over his shoulder, leaves on an old oak tree pressed against the window, turning from yellow to orange according to the retreating suns intensity, until they at last disappeared in the darkness. Meanwhile, Kristofferson frowned and stared at the floor as he searched for names and sensations from the late 1960s and early 1970s, when he was the most talked about man in this country music town. It was like everybody was in love with music, he finally offered. Everybody was in love with the creative part. And thats the only part I ever had anything to do with. Ive often felt that I was so lucky that I got here at that time, because there were people like Mickey Newbury and John Hartford. Gentle on My Mind was just a revolutionary song to me. It was light-years ahead of the stock, old-time songs. And I dont think the lines even rhyme in it!

Outside, Vanderbilt University football fans ambled down Seventeenth Avenue South after their teams embarrassing loss to Florida, their guffaws and occasional complaints trailing off toward the neighborhood bars. Kristofferson, his carriage still suggestive of his own days on the college gridiron, gestured toward the neighborhood outside, the West End, which used to be his home, admitting that the town and its music industry seemed more real in his memories. I wish I could sometimes go back to that time. It was just so creative. All the time. And our hearts and souls were totally committed to the songwriting.

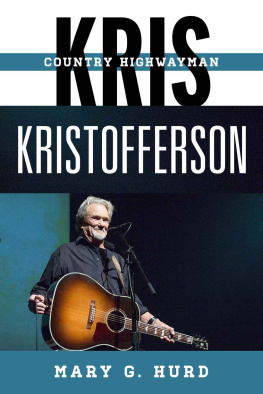

KRISTOFFERSON AND HIS friends were outlaws, servants of the songs, who chased the music the way it sounded in their heads. They resisted the music industrys unwritten rules, which prescribed the length, the meter, and the lyrical content of songs as well as how those songs were recorded in the studio. In time, the music industry bowed to their vision, shedding the old ways and accepting songs with peculiar names, like Jesus Was a Capricorn or Devil in a Sleepin Bag or The Battle of Laverne and Captain Flint. Kristoffersons songs, particularly, explored sensual love and desperate negotiations with personal devils in a rambling ballad style that sharply contrasted with the strictly tempered verse that had dominated country music for decades. He engendered a freedom of expression in Nashvilles music business, and, in his wake, other freedoms emerged.

Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson became outlaws in country music when they won the right to record with any producer and studio musicians they preferred. For decades the record companies made such decisions, but in the early 1970s Waylon and Willie began crafting a narrative that condemned their first RCA producer, Chet Atkins, the legendary guitarist who ran RCAs Nashville offices. Few people had contributed more to Nashvilles ascent as a recording center in the 1950s and 1960s than the beloved Atkins, but in the eyes of Waylon and Willie he was the man who dictated their sound and their repertory. In the outlaw story, Chet had to be removed in order to liberate Waylon and Willie.

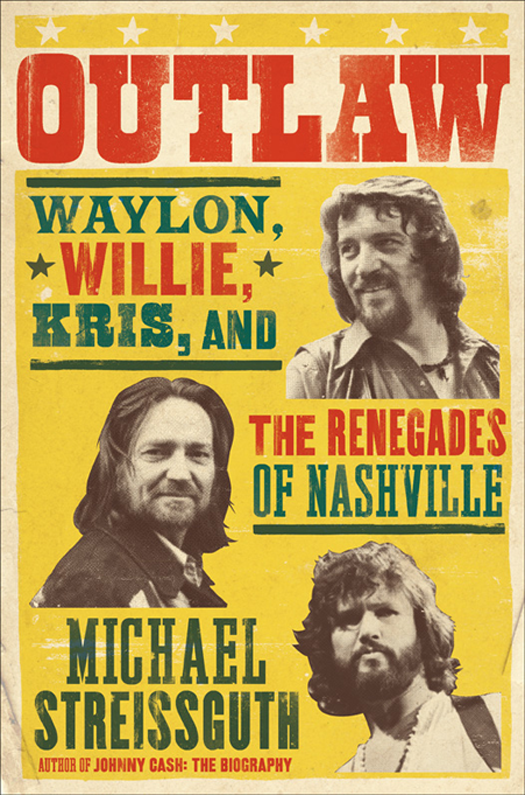

One could pin outlaw patches on dozens of men and women who discarded Nashvilles old recipes in the late 1960s and early 1970ssuch as recording artists Roger Miller and Bobby Bare and producers Fred Foster and Jack Clementbut Kristofferson, Jennings, and Nelson became Stone Mountain in outlaw lore. Predictably, music executives capitalized on the excitement over the new independence and created a companion marketing label, the outlaw movement, which in the minds of concert promoters and label bosses encompassed singers with cussed attitudes who dressed like Jesse James. Any one of them could have passed for a member of the Marshall Tucker Band, the southern rockers whom Waylon toured with and whose gold-record hit Cant You See he covered in 1976. Indeed, their solemn photos cranked up the appeal of RCAs Wanted! The Outlaws, a 1976 compilation featuring Waylon, Willie, Jessi Colter, and Tompall Glaser that became country musics first platinum album and introduced the outlaw label to the masses.

Save for Kristoffersons activism on behalf of the United Farm Workers and other causes, the scene proved vacuous politically, definitely more of a Jimmy Buffett invitation to hard partying than a call to social responsibility. But amid the hippie girls who stripped off their halter tops at Waylons shows and magazine advertisements for Willies belt buckles, the independence these men inspired rang through Nashville. As other recording artists took control of their own sessions, staff producers lost their jobs and record companies sold their Nashville studios; RCA, CBS, ABC, and the rest became packagers and marketers of Nashville-based artists, from Eddy Arnold to Tammy Wynette.

To nobodys surprise, the music made by the chief outlaws proved just as influential as their dilution of corporate control. Kristofferson inspired a singer-songwriter tide in the 1970s that swept up Rodney Crowell, Rosanne Cash, and Mary Chapin Carpenter, major stars in the 1980s, while the PG overtones of his songs echo still in todays country music. Kristofferson had arrived in Nashville in 1965 and struggled for years for recognition, working odd jobs while attempting to rein in a songwriting style that owed more to the English poet William Blake, whom he had studied in college, than to the honky-tonk king Hank Williams, whom he idolized. When Blake and Bocephus finally merged in Kristoffersons verse, song publisher and record company owner Fred Foster stepped forward to sign him. Plenty of observersincluding Fosters business partnersbelieved Kristofferson belonged back on the Nashville streets, where he had rambled and drank and soaked up songs. But by 1970 he was the talk of Nashville: Johnny Cash, Roger Miller, and Ray Price recorded his songs and hip nightclubs on the coasts embraced him. Songwriters copied his style and explored his themes, and radio stations decided that a little modern maturity sung in a Dylan style could live in the country music format.