ABOUT THE AUTHOR

DON RAUF has written more than 30 nonfiction books, including Killer Lipstick and Other Spy Gadgets, Simple Rules for Card Games, Psychology of Serial Killers: Historical Serial Killers, The French and Indian War, The Rise and Fall of the Ottoman Empire, and the book series Freaky Phenomena. He has contributed to the books Weird Canada and American Inventions. He is a regular writer for Mental Floss and Health-Day. An avid bike rider, Don lives in Seattle with his wife, Monique, and son, Leo.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DK/Penguin Random House. Bicycle: The Definitive History. New York City: DK/Penguin Random House, 2016.

Dzierzak, Lou. Schwinn. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company, 2002.

Love, William. Classic Schwinn Bicycles. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company, 2003.

Mitchel, Doug. Standard Catalog of Schwinn Bicycles 1895-2004. Iola, Wisconsin: KP Books, 2004.

Pridmore, Jay and Jim Hurd. Schwinn Bicycles. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International Publishers & Wholesalers, 1996.

Rea, Steven. Hollywood Rides a Bike. Santa Monica, California: Angel City Press, 2012.

The Schwinn display at the Bicycle Museum of America. Author photo

Chapter One

THE BIRTH OF THE MODERN BICYCLE

AROUND THE TIME Ignaz Schwinn arrived into the world on April 1, 1860, in Hardheim, Germany, the first real incarnation of the modern-day bicycle was also being born. In that decade, the Michaux family, coachbuilders from Paris, developed a two-wheeler with a wooden frame and two steel wheels. Riders propelled the contraption along using pedals and cranks. (Historians believe that a mechanic by the name of Pierre Lallement, who worked for the Michaux business, may have also played a role; he received a US patent for a two-wheeled vehicle with crank pedals in 1866.)

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

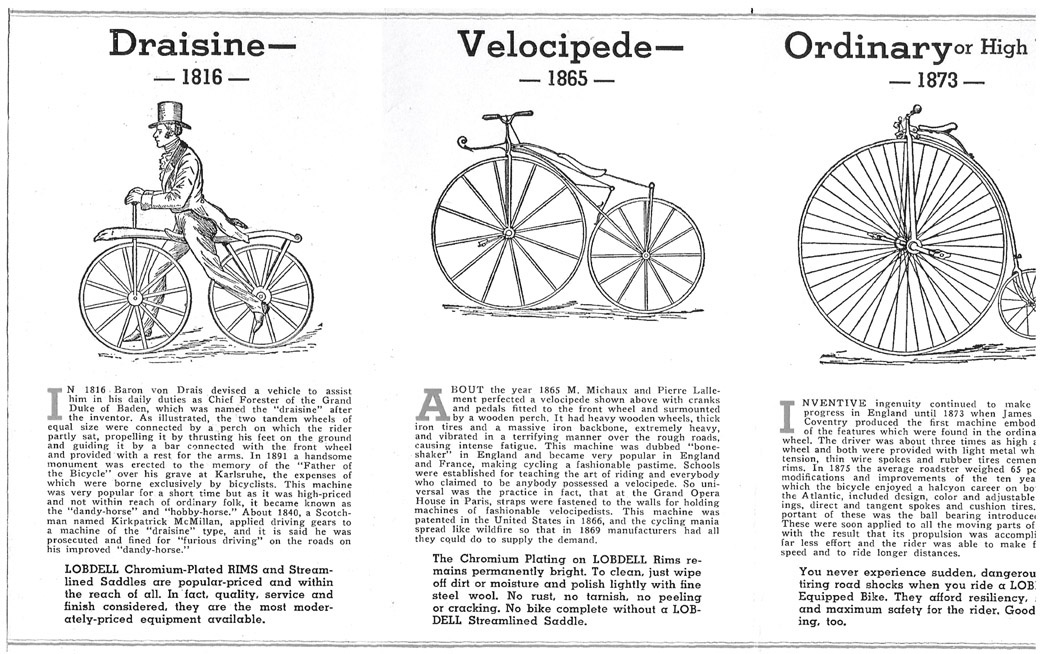

This innovation in pedal power marked the real beginning of the modern bicycle. Prior to this, German Karl Drais had created a two-wheeled vehicle called the hobbyhorse (aka the running machine, and sometimes referred to as the Draisine) in 1816. Riders sat in a saddle and steered with wooden handlebars, but to move the hobbyhorse forward they had to push their feet along the ground. The pedal-powered contraption from Michaux was dubbed the velocipede, but it quickly gained the nickname of boneshaker, as riders were jarred by every bump in the road, primarily rattled by the rough cobblestone streets.

This timeline shows the early development of the modern bicycle, from the Draisine hobbyhorse to pedal-powered machines, such as the velocipede and high wheel. Courtesy of the Bicycle Museum of America

Following the boneshaker, the high wheel bicycle rolled into the world. Because its two wheels looked like a big English penny coin leading a smaller farthing coin, the public nicknamed this vehicle the penny-farthing. Others called it the ordinary. With an enormous front wheel, a cyclist could move farther with each rotation of the pedals compared to the old boneshaker. Although the high wheel bicycle might have traveled faster and provided more comfort with its rubber tires, cycling required daredevillike skills. Riders had to hoist themselves high into the saddle and quickly gain their balance. Any small pothole could send cyclists toppling over from their high perch. Understandably, because of its precarious nature, the vehicle had limited appeal. The high wheel bicycle was deemed too riskyand perhaps risqufor women, so manufacturers made a special tricycle directed toward females.

While the penny-farthing was one of the first two-wheelers to be called a bicycle, the next major innovation became the model for the bicycle as we know it today. In 1885, John Kemp Starley produced the Rover safety bicycle. The invention featured two same-sized wheels, a frame similar to todays bikes, a steerable front wheel, and a chain drive linking the rear wheel to pedals attached to the frame with a sprocket. The concept was literally a turning point in bicycle history. With its two smaller wheels, this machine was much safer than the penny-farthinghence the name. The safety bicycle design, with its diamond-style frame, would remain the foundation of bicycle construction for the next hundred-plus years.

The Boston Bicycle Club displaying their high wheelers in Wellesley, Massachusetts, 1894. Courtesy of the Bicycle Museum of America

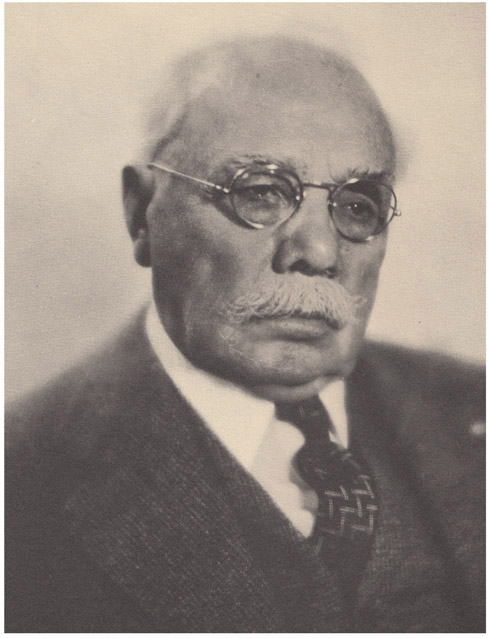

A talented craftsman and machinist, Ignaz Schwinn developed a keen interest in bicycle building at a young age. Because he was also a shrewd businessman, Schwinn established the dominant American bicycle brand of the twentieth century. Courtesy of the Bicycle Museum of America

Then, two years later, in 1887, John Dunlap struck upon another pivotal improvement when he developed a pneumatic, or air-filled, tire for his sons tricycle. Compressed air helped carry weight and absorb shocks. Using pneumatic tires on bicycles added a level of comfort that would boost the popularity of two-wheeled transportation even further.

With the introduction of these innovations, cycle-making took off in England at the end of the 1880s and quickly spread.

A PASSION FOR PEDAL POWER

As a mechanical engineer, Schwinn was captivated with the breakthrough of the safety bike. The trained machinist had learned extensively about metals and industrial tools while employed at various factories in Germany. In the mid-1880s as he labored at different bicycle shops, Schwinn dreamed of producing his own safety bicycle for the public. He approached manufacturers with his designs, but many werent yet sold on the basic safety bike concept; they wanted to stick with a proven thing: the high wheeler.

Schwinn, however, firmly believed in the cutting-edge idea. Eventually, he sold Heinrich Kleyer on his safety bicycle plan. Kleyer hired Schwinn to work in Frankfurt at his Kleyer Bicycle Works, where the company produced high wheelers under the brand name Adler (German for eagle). After Kleyer moved ahead, changing over from high wheelers to safeties in 1887, Schwinn became general manager of the plant at age twenty-nine. At the Kleyer factory, Schwinn made a diamond-frame bicycle that quickly became a hit, making the Kleyer Adler bicycles hugely popular in Germany.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Schwinn, however, grew restless. Realizing he couldnt rise above the position of factory manager at Kleyer, Schwinn set his sights on bigger and better things. He saw America as the land of opportunity. In the United States, the 1880s and 90s became known as the Age of Immigration, as waves of Europeans streamed into the country. Many were attracted by the unprecedented technological innovation and industrialization taking place there. While visiting relatives in Hamburg in 1891, Schwinn decided to buy a ticket aboard a ship bound for America. When he arrived, he found his manufacturing know-how in the bicycle business was in high demand, as the bicycle craze was just kicking into high gear.