Whenever civilized nations occupy an island, they turn it either into a fortress or a prison.

PASCAL

Island prisons begin with Crete, where Icarus escaped from the labyrinth with his son Daedalus by fashioning wings and flying toward the sun. Napoleon imprisoned at Saint Helena, Dreyfus at Devils Island, and Nelson Mandela at Robben Island are more recent inmates of infamous and isolated prisons. Chteau dIf, a French island prison a mile or so off Marseille, housed the fictional Count of Monte Cristo, while Mussolini sent political opponents to the Lipari Islands off the Italian coast. In his Gulag Archipelago, Alexander Solzhenitsyn described the notorious Solovki island monastery prison, at one time also the home of the writer Maxim Gorky. On the East Coast of the United States, Governors Island, a former U.S. military base in New York harbor, held a prison where Revolutionary and Civil War spies were hanged. And on the West Coast was Alcatraz, the federal prison where there were no executions but where no one ever escaped.

Architecture plays a crucial role in understanding Alcatraz because it encloses the prisons mystery and danger. The well-known but opaque and imposing cellhouse became the dominant image of the island, visiblefrom a distancethroughout the Bay Area. It stood as the external expression of the prisons internal purposepunishment, discipline, and controlwhile maintaining the intrigue and secrecy of the prison by revealing nothing to the public. The harsh microclimate of the island began to undermine the cellhouses materials and structural integrity, however, and it soon began to deteriorate. And as it began to wear down, so too did the purpose of the prison, which closed in 1963.

And its name, The Rock? It originated with the soldiers stationed there during World War II to guard the harbor, the term conveying the isolation and remoteness of the island. No other name would suit the barren land and rocky formations.

Until recently, distance has always defined Alcatraz. From the brick and masonry fortress and Citadel to the concrete and imposing cellblock, one can see its history in its buildings and understand its past. The variety of styles, from the Third System of defensive forts to the Victorian and mission revival styles, link the island to the mainland and yet maintain its distinction. The federal style of the massive cellblock (started in 1909) contrasts with the more discrete and individualistic styles of the Officers Quarters or the New Industries Building, built with an eye on the modern.

The very distance and secrecy of Alcatraz, imposed by nature and reiterated by its architecture, increased attention on the things most visible from the mainland: its buildings. With their enclosed and hidden functions, the structures intensified the curiosity of the public (normally prevented from visiting prisons) as to exactly what went on there. And when the prison was finally opened to the public, the number of visitors was staggering. It was a chance to find out the secrets of the island, which only the buildings, seen from a distance, could suggestor hide.

This book tells the long history of Alcatraz through its architecture and inhabitants, from its earliest discovery through its use as a military fortress, federal penitentiary, occupied site, and finally national park. It is a story of the constant remaking of the island, physically and architecturally, and how this isolated sandstone rock became one of Americas most visited tourist attractions.

WHATS IN A NAME?

Alcatrazes, Alcatras, Alcatrasas, Alcatraces, Alcatrose, Alcatrazas, Alcatrzos, Alcatases, Alcatrasses, Alcatraz

ISLAND NAMES, NINETEENTH-CENTURY U.S. ARMY REPORTS

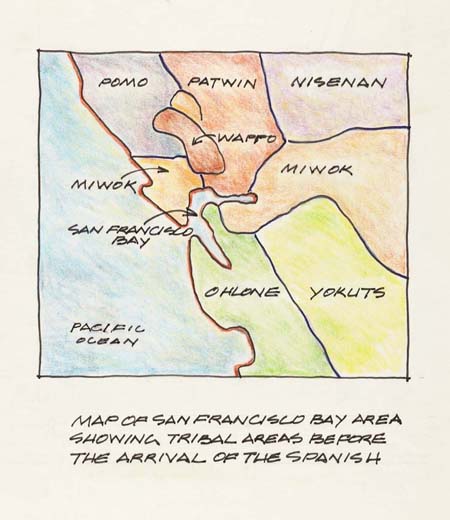

It was not until 1542 that a Spanish explorer named Cabrillo became the first European to navigate the coast of present-day California. Throughout the seventeenth century, more Spaniards arrived to explore the coast, and on November 2, 1769, Gaspar de Portola, on an overland journey, discovered San Francisco Bayby accident. He was looking for Monterey Bay but found something larger. Six years later, the Spanish explorer Juan Manuel de Ayala and his flotilla arrived by sea.

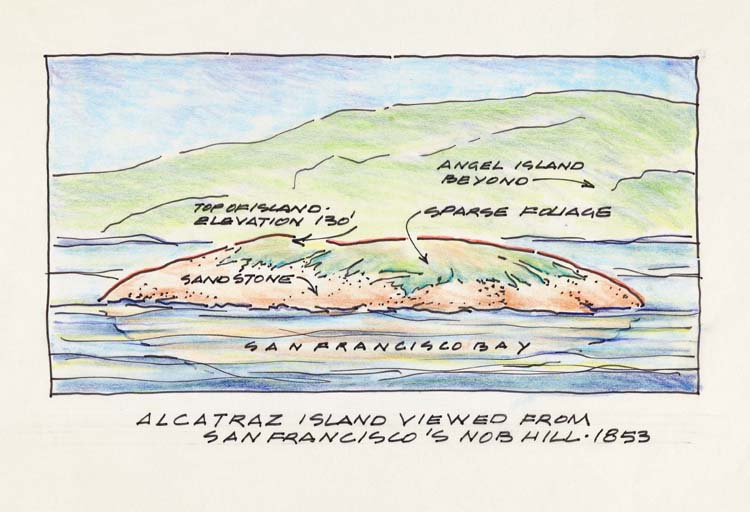

Ayala, piloting the first recorded ship to enter San Francisco Bay on August 5, 1775, named what is today Yerba Buena Island, two miles east of Alcatraz, Alcatraces after its plentiful pelicans. For the next fifty years, Spanish charts identified the modern Yerba Buena as Alcatraces, while Alcatraz Island remained an anonymous, if large, rock in the middle of the bay, the tip of a submerged mountain. ()

The islands remained so named (and unnamed) until 1827, when a British officer, Captain Fredrick Beechey, shifted the names on Ayalas map, giving the designations used today. He moved the name Alcatraces to one of the unnamed rocks inside the Golden Gate, and the island Ayala originally named Isla de los Alcatraces became Yerba Buena (good herb). Until 1822, Alcatraz technically remained the property of the king of Spain. When Mexico achieved independence, however, jurisdiction shifted to the new country, although there was little interest in the island until 1846. That year, Julian Workman, a naturalized Mexican citizen, obtained a land grant; the only condition was that he had to establish a navigation light.

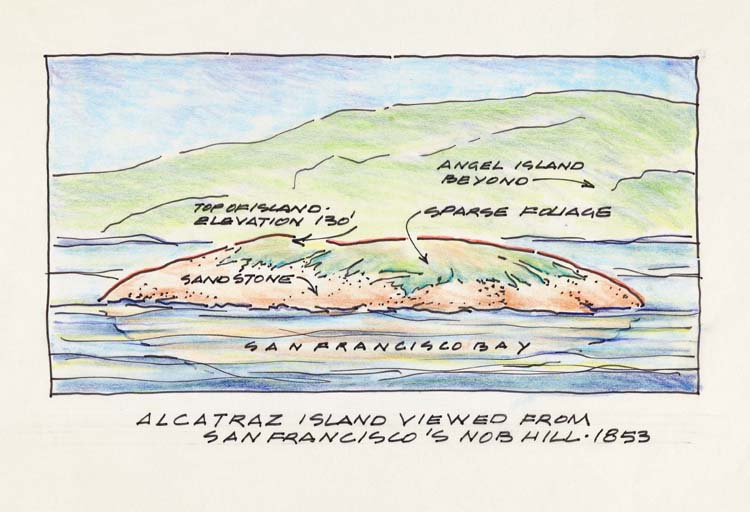

Clockwise from top: Angel Island Beyond, Sparse Foliage, San Francisco Bay, Sandstone, Top of Island - Elevation 130'.

Beneath image: Alcatraz Island viewed from San Francisco's Nob Hill. 1853.

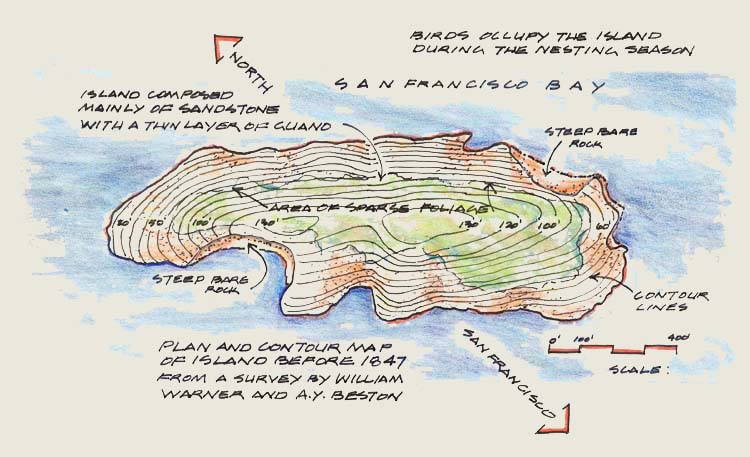

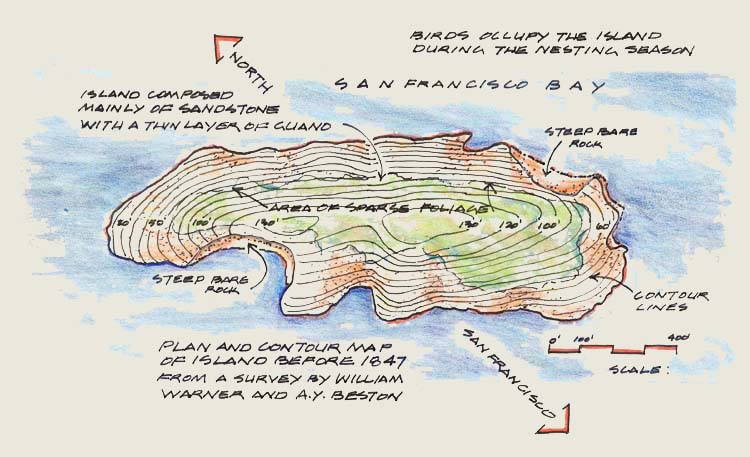

Above Image: Birds occupy the island during the nesting season.

Outer circle, clockwise from top: San Francisco Bay, Steep bare rock, Contour lines, Scale: 0', 100', 400', San Francisco ->, Steep bare rock, Island composed mainly of sandstone with a thin layer of guano, North ->.

Inner circle, top: Area of sparse foliage.

Inner circle, bottom: 80', 50', 100', 130', 130', 120', 100', 60'.

Beneath Image: Plan and contour map of island before 1847. From a survey by William Warner and A.Y. Beston.

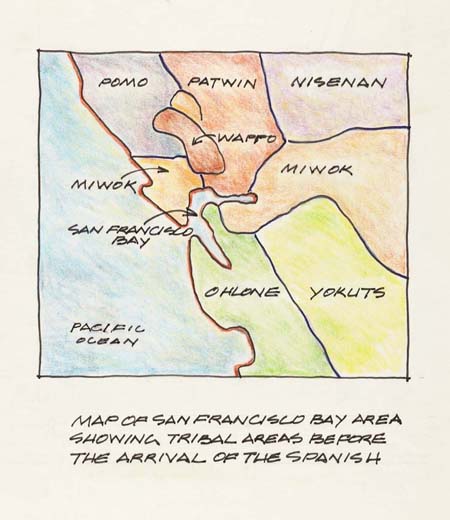

Clockwise from top: Patwin, Wappo, Nisenan, Miwok, Yokuts, Ohlone, Pacific Ocean, San Francisco Bay, Miwok, Pomo.

Beneath image: Map of San Francisco Bay Area showing tribal areas before the arrival of the Spanish.

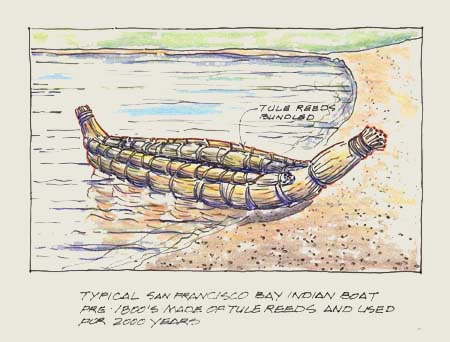

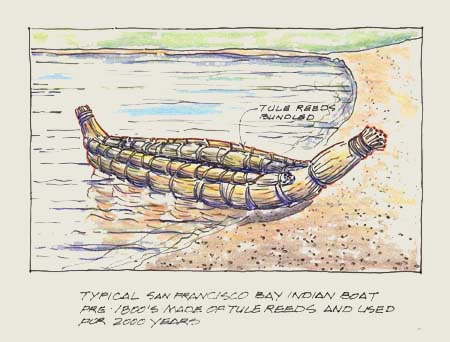

Inside image: Tule reeds bundled.

Beneath image: Typical San Francisco Bay Indian boat pre-1800s made of tule reeds and used for 2000 years.

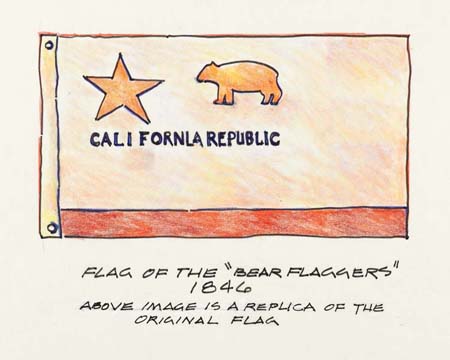

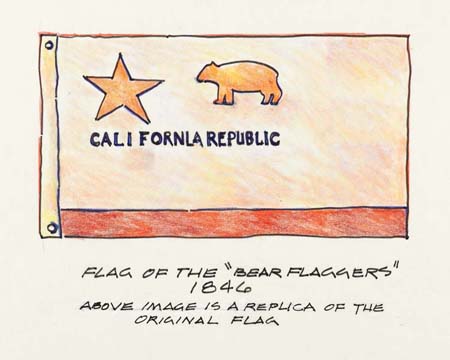

Beneath image: Flag of the Bear Flaggers. 1846. Above image is a replica of the original flag.

Text in image reads California Republic.

At the conclusion of the Mexican-American war in 1848, the United States refused to recognize all private claims of ownership: The island became public land, secured from Mexico. Alcatraz became the property of the U.S. government. ()

CHAPTER 2

THE DEFENSIVE TRIANGLE: