BAY BRIDGE

HISTORY AND DESIGN OF A NEW ICON

Donald MacDonald and Ira Nadel

Text copyright 2013 by Donald MacDonald and Ira Nadel. Illustrations copyright 2013 by Donald MacDonald.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-4521-2731-6

The Library of Congress has previously cataloged this title under:

ISBN: 978-1-4521-1326-5

Design by Lydia Ortiz

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, CA 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

THE TITAN

OF BRIDGES

The January 1933 issue of Popular Mechanics featured a new engineering marvel on the West Coast: an innovative bridge that would become the largest suspension bridge in the world upon its completion. With the sobriquet The Titan of Bridges, the new San FranciscoOakland Bay Bridge, shortened to the Bay Bridge, would be an engineering and transportation wonder solving the problem of increased population and automobile traffic between the East Bay and San Francisco. Through rapid planningit took only two years to design and three to buildthe new link between Oakland and San Francisco would quickly prove to be a vital element in the economic growth of the area.

Longer than its competitor, the Golden Gate Bridge, which would be inaugurated six months after the Bay Bridge opened in November 1936, the Titan remained continuously in use from 1936 until 1989, when the Loma Prieta earthquake caused a fifty-foot roadway section to collapse, closing the bridge for one month and causing widespread concern over its safety.

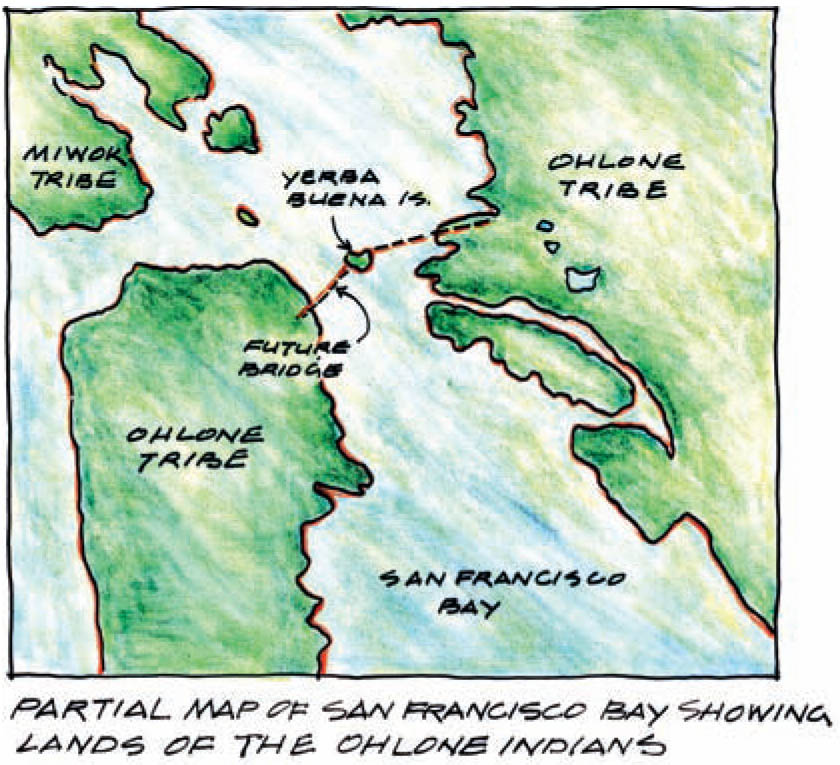

Surprisingly, this $77 million public works project, undertaken during the Depression, was approved, designed, and built both without a popular vote and with great speed. Indeed, political and social consensus supporting the bridge was a unique feature of an exceptional structure, actually two bridges: the West Span, a double suspension bridge linked by a giant anchorage between San Francisco and Yerba Buena Island, and the East Span, a cantilevered truss bridge between Yerba Buena Island and Oakland. But the purposeful construction of the 1936 bridge is in sharp contrast to the delays, wrangling, and cost overruns of the new East Span. Called the White Span because of its distinctive 525 ft. white tower and roadway, the new bridge did not begin construction until 2004 and will not be completed until September 2013, twenty-four years after the 1989 earthquake.

How all this this came about and how the worlds longest single-tower self-anchored suspension bridge became the choice for the new East Span is the story of this book, co-authored and illustrated by Donald MacDonald, the architect who designed its signature structure.

1

WHATS

IN A NAME?

Yerba Buena Island is a natural outcropping in San Francisco Bay, approximately one and a quarter miles from San Francisco, and is the touchdown for the East and West spans of the original Bay Bridge. First known as Sea Bird Island, it became Goat Island about 1836 when a Captain Gorham Nye placed goats imported from the Sandwich Islands on the small landmass for sale to trading vessels. He moved them to the island because they had been destroying the flowers in his San Francisco home, but they reproduced so rapidlyby 1849 there were nearly a thousandthe name Goat Island seemed appropriate. Wood Island was the next designation, and sometime later it became Yerba Buena, the name originating from a nearby town because of an aromatic trailing vine that covered the slopes of the town and the island. The plant, whose common name is an English form of the Spanish hierba buena , meaning good herb, is related to the mint family.

The first legislature of California officially established Yerba Buena as the islands name in February 1850but it didnt stick. By 1895, the U.S. Geographic Board changed it back to Goat Island, which lasted until June 1931. The Geographic Board then reversed itself, restoring the Spanish Yerba Buena in response to demands to return to its official, legislatively approved name.

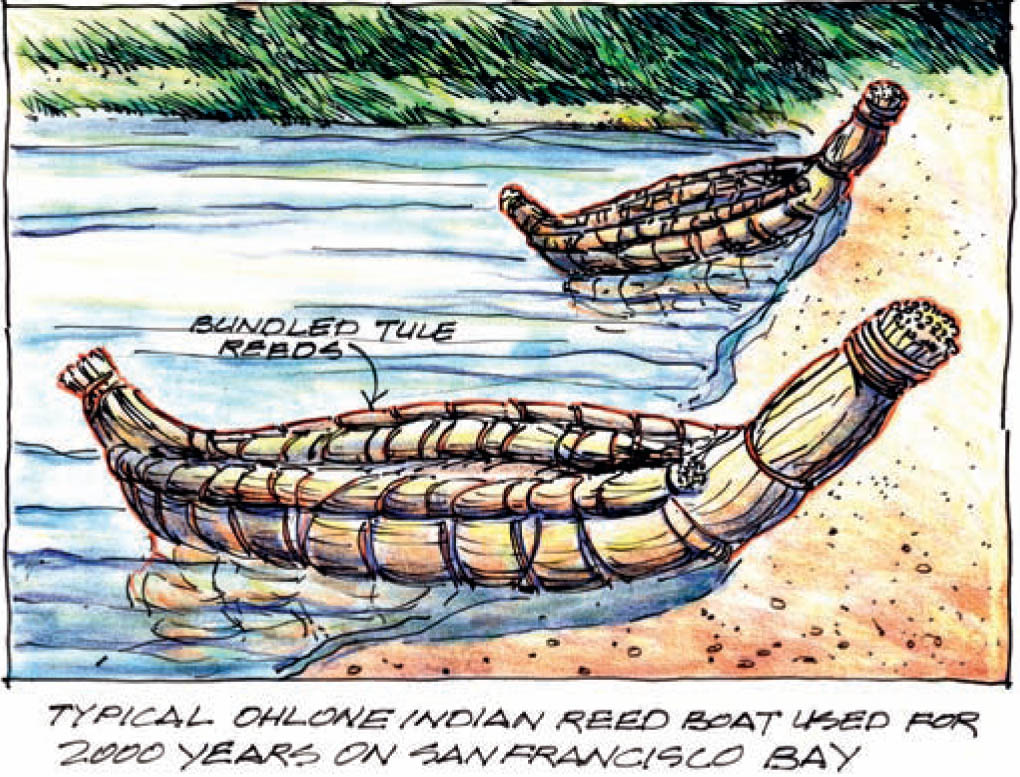

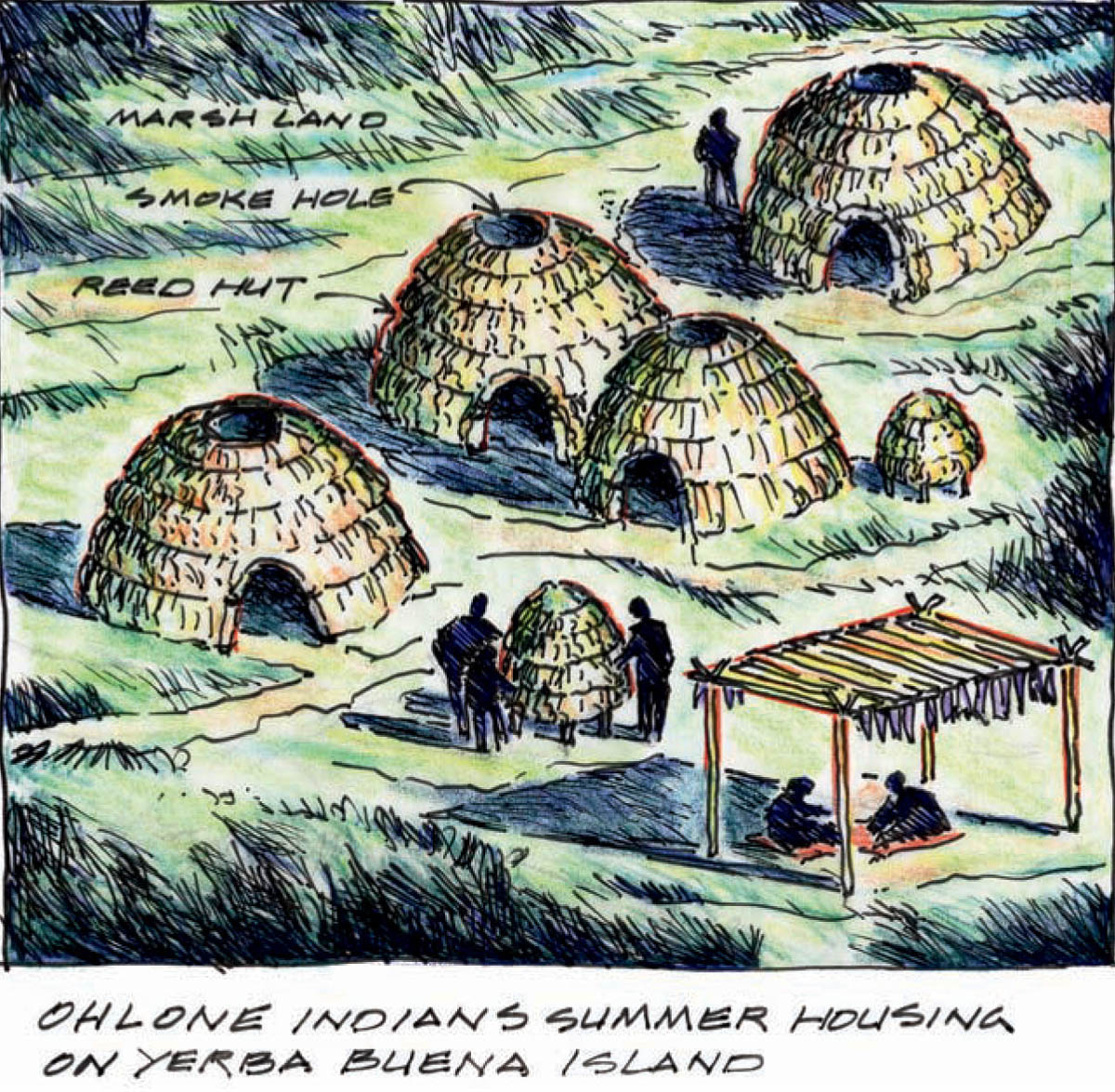

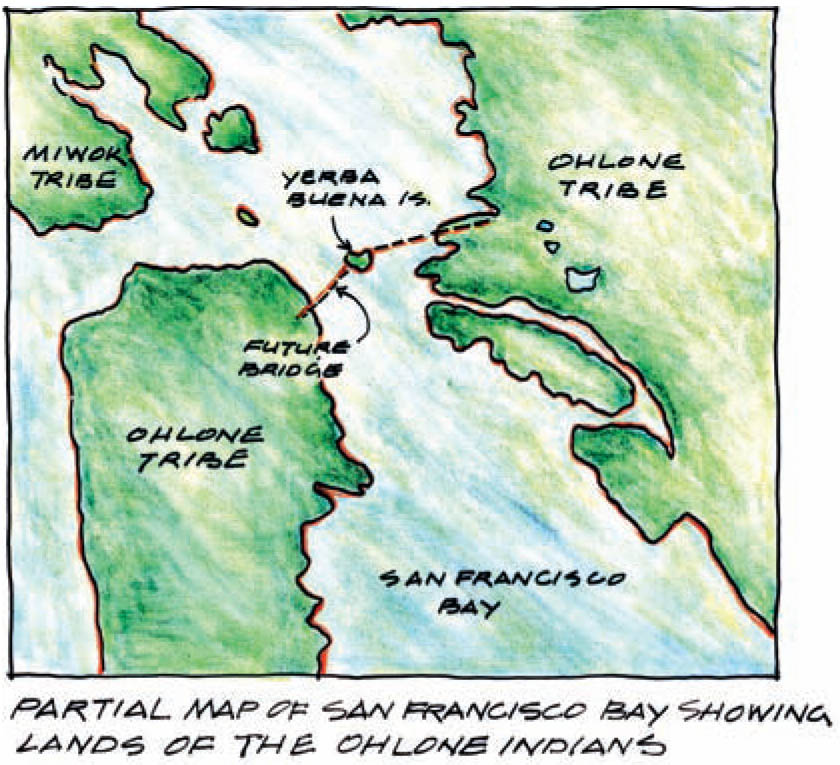

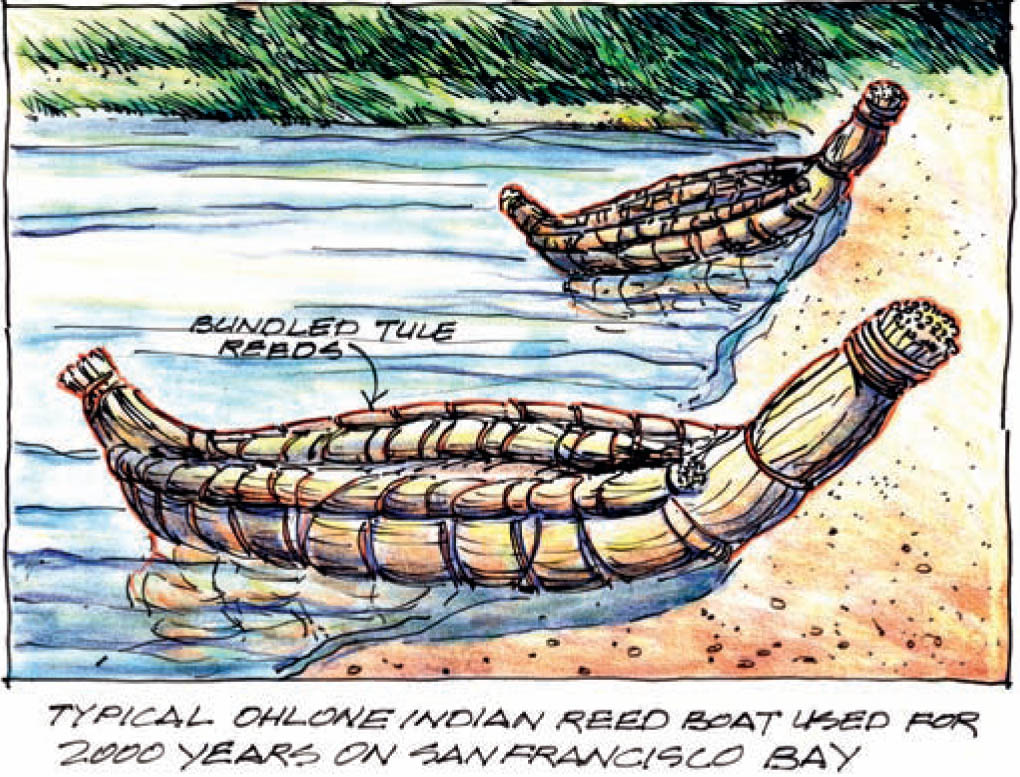

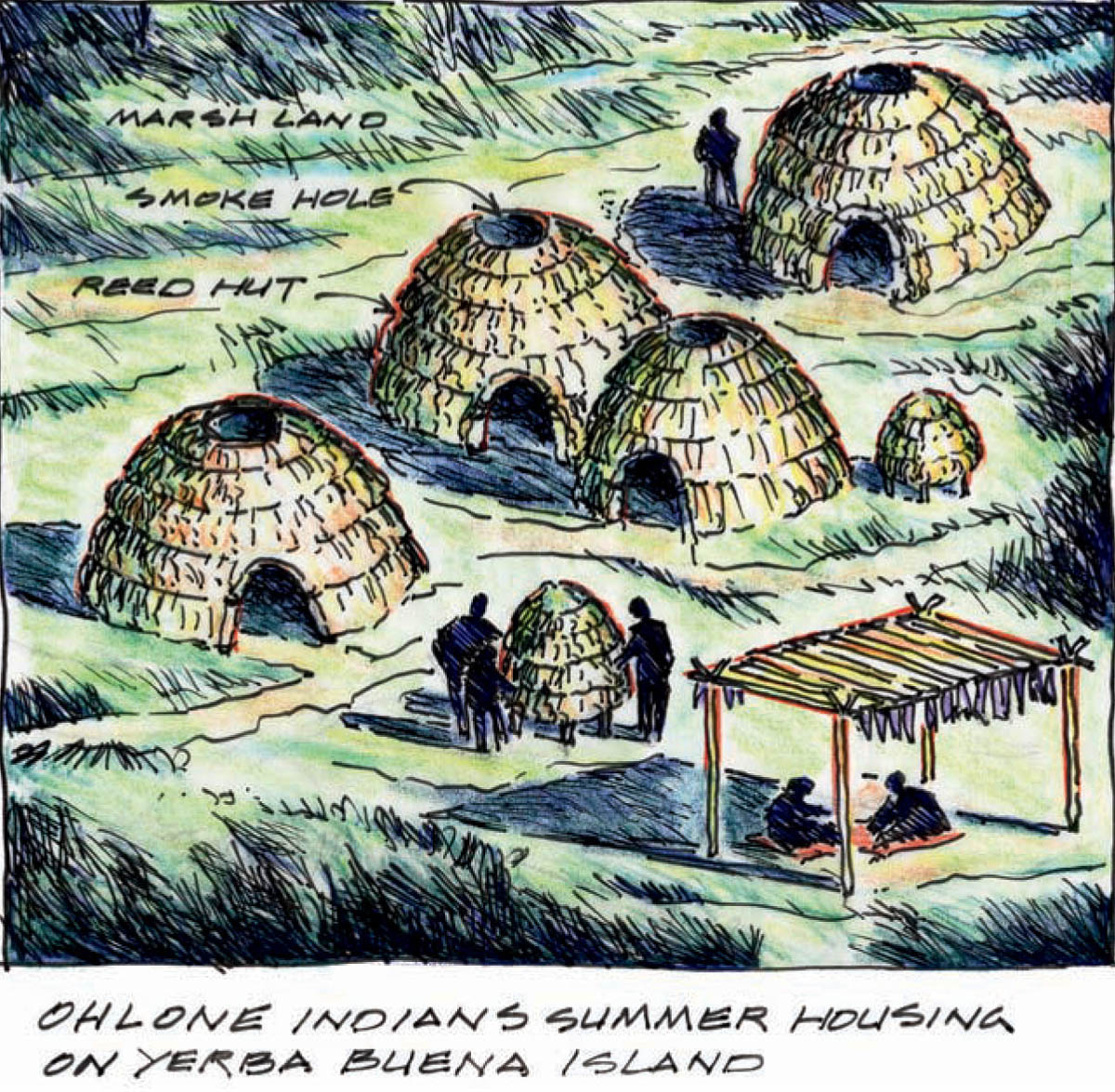

Centuries before the settlement of the Bay Area, Ohlone Native Americans fished in the area and explored the island, traveling there in either canoes or tule barges () . The buildings ranged from the ruins of old houses to bones, shells, and cremating pits. Bernard later returned to live on the island for a short time.

Figures 1 & 2

Figure 3

The island has had its share of mystery, notably a legend of buried treasure, as smuggling was a particularly successful business in the 1830s, with goods taken from ships arriving in the harbor and hidden on the rocky outcroppings; the alleged items included opium and silver. In 1837, a Spanish sloop returning to Spain with the wealth of the Mission Dolores crashed on the island in a storm. It was likely wrecked on the northern point, with most, but not all, of its treasure saved. Survivors apparently buried much of the church plate and silver on the island, although they never returned to claim it. Coupled with stories from the California Gold Rush of 1849, numerous prospecting parties headed for the island, but rarely with any luck. During a fire in San Francisco, however, a great deal of stolen gold and silver was buried on the island. Suspected to be part of the Mission Dolores treasure, it was later recovered with the help of the police.

Spanish explorers sailed past the inland island but some squatters during the early California Gold Rush called it home. Sailors made excursions to the island from their ships anchored in the bay. By 1852, the government realized the islands strategic importance, proposing to place gun batteries there, thereby including it in a third line of fortifications, joining earlier forts on Alcatraz and Fort Point.

The military reservation of the late nineteenth century became a Quartermaster depot, eventually being transferred to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Officers stationed there later brought their families. The presence of the military personnel and a small community meant the need for a cemetery on the west end of the island, where markers reach back to 1852. Of course, death had always been a presence on the island. Almost fifty years later, a pair of skeletons were found buried in sitting positions, while on the eastern part of the island specimens of stone mortar, stone pipes, and a dog skeleton were locatedfurther evidence that the island had been inhabited for a very long time.

Earlier in the nineteenth century, the death of Captain Edward Lindsey aboard his ship, the Palmyra, while it was docked in the bay in August 1852 underscored the importance of the island. An elaborate funeral cortege rowed out from the ship, led by a longboat with four oarsmen, followed by a line of ships boats headed for the islands graveyard for a full naval burial. The most unusual burial, however, was that of a despondent Italian nobleman who, in the 1850s, after Garibaldis seizing power from the king of Italy, moved to San Francisco. But even in his new life, he remained discouraged and unhappy and ultimately decided to take his own life. He crossed to Yerba Buena Island one night and dug his own grave, arranging the dirt by means of boards set upon a trigger so that when he fired his gun and fell into the grave, the dirt would tumble on top of him. In this way, he buried himself. When his body was discovered a few days later, however, the coroner insisted it be removed and taken to the city for burial in a paupers grave.