BRIDGES

BRIDGES

The Science and Art of the

Worlds Most Inspiring Structures

DAVID BLOCKLEY

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

David Blockley 2010

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Library of Congress Control Number: 2009942577

Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

Clays Ltd, St Ives Plc

ISBN 9780199543595

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

1. BRIDGES ARE BATS:

Why we build bridges

2. UNDERNEATH THE ARCHES:

Bridges need good foundations

3. BENDING IT:

Bridges need strong structure

4. ALL TRUSSED UP:

Interdependence creates emergence

5. LET IT ALL HANG DOWN:

Structuring using tension

6. HOW SAFE IS SAFE ENOUGH?:

Incomplete science

7. BRIDGES BUILT BY PEOPLE FOR PEOPLE:

Processes for joined-up thinking

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Very many people have helped me prepare this book. Firstly I owe an enormous debt to Joanna Allsop, who made many suggestions to make the book accessible to non-technical readers. She read every word and pointed me to the material on Michelangelos bridge building in the Sistine Chapel.

Robert Gregory and Mike Barnes read the whole book and also made many helpful comments. Ian Firth, John Macdonald, and Jolyon Gill read and advised me on the dynamics of footbridges. Pat Dallard, Michael Willford, and Roger Ridsdill-Smith read and made helpful suggestions to ground my account of the problems with the London Millennium Bridge in the experience of those who took part. David Weston has provided information about the Bradford on Avon Arch Bridge.

I thank Robert and Ros Gregory for being such good and remarkably patient travelling companions on our bridge-photographing tours in Europethe photographs , which is based on very limited published material. Richard Buxton suggested I might find material in Herodotus and I did. Patricia Rogers tracked down so much material for me in the University of Bristol Library. Thank you also to the many others who helped directly or indirectly through their conversations, particularly Joan Ramon Casas, Priyan Dias, David Elms, David Harvey, Lorenzo Van Wijk, Guido Renda, Albert Bernardini, Arturo Bignoli, Bob McKittrick, Adam Crewe, Jitendra Agarwal, Mike Shears, Malcolm Fletcher, and Michael Dickson. I send a special word of thanks to Roy Severn and Patrick and Trudie Godfrey for their direct help and encouragement.

I acknowledge permission from the Uffizzi Gallery Florence to use on the diagrams in ASCE Proceedings 72 (1946).

I thank the following for permission to quotes extracts: Burlington Magazine for text by John Beldon Scott; Penguin Books for material from Herodotus, The Histories; the Institution of Structural Engineers for text from the Presidential address by Oleg Kerensky; Simon Caulkin for material from an article in the Observer newspaper; and Michael E McIntyre for text from his website.

Particular thanks to David Doran for encouraging me to write this book and, through him, to Keith Whittles. Thanks also to Emma Marchant and Fiona Vlemmiks at Oxford University Press and copy editors Charles Lauder Jr. and Paul Beverley. However, the biggest thanks of all go to OUP editor Latha Menon, firstly for having faith in me when she saw my first draft and then for guiding and eventually commissioning the book and for helping to develop it into something worth publishing.

Last, but by no means least, thanks to my wife, Karen, for her long suffering during the gestation, writing, and production of the book and her unfailing love and support and endless cups of tea.

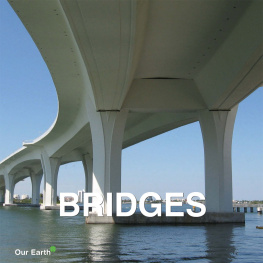

Introduction

Bridges touch all our livesevery day we are likely to cross or go under a bridge. But how many of us stop to consider how the bridge works and what sort of people designed and built it? In this book we will explore how we can read a bridge like a book, to understand how it works, and to appreciate its aesthetic, social, and engineering value.

There are three practical requirements for a successful bridgefirm foundations, strong structure, and effective working. These will form the chapters within which we will find paragraphs, sentences, words, and letters. The grammar of how bridges are put together will be based on combinations of four substructural typesBATSbeams, arches, trusses, and suspensions. For example, the Golden Gate Bridge is a suspension Bridge with a roadway deck on a stiff truss beam.

Bridges are icons for whole citiesthink of New Yorks Brooklyn Bridge, Sydneys Harbour Bridge, and Brunels Clifton Bridge in Bristol where I live. Traditionally architects have not been involved in bridge design because bridges have been conceived as raw engineered structure. Yet bridges are also a form of functional public artthey can delight or be an eyesore. Now architects and sculptors can and do contribute to the aesthetics of bridges to improve their impact in our public spaces. One of the finest examples is the Millau Viaduct in France which certainly has the wow factor.

Bridge building is a magnificent example of the practical and everyday use of science. Unfortunately there are always gaps between what we know, what we do, and why things go wrong. Bridge engineers must manage risks carefully. They know that information has a pedigree which they must understand. The rare cases of bridge failures can help us to learn some valuable lessons that also apply to other walks of life. One example is that failure conditions can incubate over long periods and we can learn to spot them. Another is that partial or silo thinking with a lack of joined-up inadequate processes do typify technical and organizational failures.

Next page