About the Author

David Ian Blockley is an Emeritus Professor of Engineering at the University of Bristol, UK. He was born in Derbyshire, England, in 1941. He graduated from the University of Sheffield in 1964 and gained his PhD there in 1967. For 2 years, he was a Development Engineer with the British Constructional Steelwork Association in London working on design development. In 1969, he became a Lecturer in Civil Engineering at the University of Bristol, was promoted to a readership in 1982 and a personal Chair in 1989. In the same year, he was appointed Head of the Department of Civil Engineering, University of Bristol until 1994 when he was elected Dean of Engineering at the University of Bristol from 1994 to 1998. He was reappointed as the Head of Civil Engineering in 2002 until his retirement in 2006.

David Ian Blockley is an Emeritus Professor of Engineering at the University of Bristol, UK. He was born in Derbyshire, England, in 1941. He graduated from the University of Sheffield in 1964 and gained his PhD there in 1967. For 2 years, he was a Development Engineer with the British Constructional Steelwork Association in London working on design development. In 1969, he became a Lecturer in Civil Engineering at the University of Bristol, was promoted to a readership in 1982 and a personal Chair in 1989. In the same year, he was appointed Head of the Department of Civil Engineering, University of Bristol until 1994 when he was elected Dean of Engineering at the University of Bristol from 1994 to 1998. He was reappointed as the Head of Civil Engineering in 2002 until his retirement in 2006.

He is a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering, of the Institution of Civil Engineers, of the Institution of Structural Engineers and of the Royal Society of Arts. He was the President of the Institution of Structural Engineers during 20012002. He is a Corresponding Member of the Argentinean Academy of Science and of Engineering. He was a Non-Executive Director of Bristol Water plc from 1998 to 2007. He is the author of over 180 papers and seven books, and has won several technical awards for his work, including The Telford Gold Medal of the Institution of Civil Engineers. His first four books were technical and written for other engineers, but his most recent three books have been written for the general reader, namely Bridges: The Science and Art of the Worlds Most Inspiring Structures (2010, Oxford University Press, UK), Engineering: A Very Short Introduction (2012, Oxford University Press, UK) and Structural Engineering: A Very Short Introduction (2014, Oxford University Press, UK).

Chapter 1

Abstract

I present a classification of basic types of structural failure and then expand it into a set of statements which could be assessed subjectively as the parameters of a prediction process. This process is intended to account for a structure failing due to causes other than stochastic variations in load and strength. The parameters are assessed for 23 major structural accidents and one existing structure, and are analyzed using a simple numerical interpretation. The accidents are ranked in their order of inevitability. Human errors of one form or another proved to be the dominant reasons for the failures considered.

Introduction

There has been in recent years an upsurge of interest amongst engineers in matters related to structural accidents. Reports of inquiries into recent accidents have become compulsive reading, whilst at the same time, the redrafting of codes of practice into the limit state format has stimulated inquiry into the use of probability theory to determine suitable partial factors. An increasing concern about the way actual structures behave rather than idealized theoretical models or isolated laboratory tests on physical models or elements of structures is another aspect of this interest.

One of the major difficulties in discussing this subject is the problem which has existed since Galileo, the communications gap that often exists between the practising engineer and the research worker. Many engineers believe that, for instance, probability theory will be of little help in understanding the basic causes of structural failures. Slightly altering the values used for safety factors (be they total or partial) will be of little consequence in this regard. It is difficult, on the other hand, to wrap up problems such as poor site control, errors of judgement and pressures due to shortage of time and money, into mathematical models or rules of procedure to be written into codes of practice.

Probability theory is a mathematics of uncertainty. Its use requires a different way of thinking about mathematics than the traditional mathematics most engineers were taught. Many engineers cannot see any reason why they should bother. Most research workers in the field of structural safety would agree that probability theory is an essential tool in helping to predict the actual behaviour of a structure.

The purpose of this chapter is to review and classify some structural failures and to consider ways in which predictions of the likelihood of possible future structural accidents can be performed.

Design Process

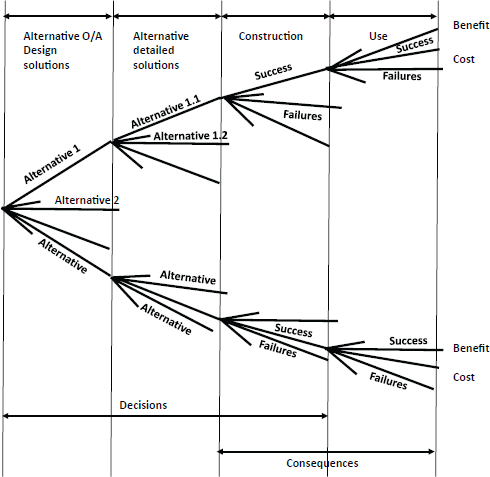

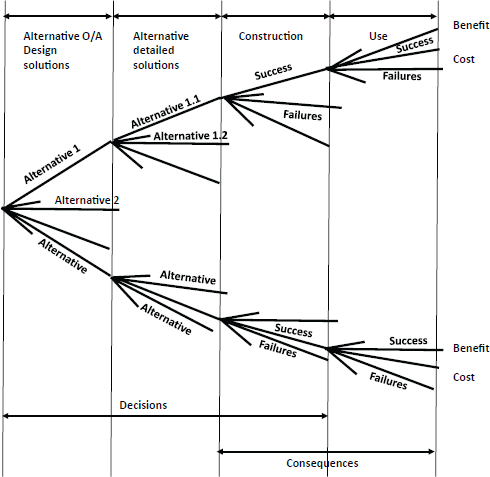

In order to discuss a classification of structural accidents, it may be instructive first briefly to examine the design process in a very general overall way. shows a simplified decision tree demonstrating the overall decision routes facing the structural designer. This is intended to be a conceptual model made at the design stage of the general decisions yet to be faced. The first two decision paths to be taken (those of alternative structural forms) are the designers choice using mainly professional information. The third path, the construction process, will be partially under the control of the contractor and designer, and the final path, the use of the structure, will be largely the consequence of these earlier decisions.

There are obviously many overall design solutions to any problem. A single-storey shed may, for instance, be a concrete portal, a steel portal or a steel truss: this is the first decision path. There is a multitude of detailed design decisions concerned with the spacing of frames, the lateral bracing, design of joints, etc., which are represented by a single line in will occur and the structure will be damaged or collapse, and a cost penalty incurred.

Figure 1.1. Overall project decision tree.

The central problem of the designer is to design his structure economically and aesthetically so that the probability of each of these unacceptable events or accidents is acceptably low. In order to make his decisions, the designer has certain tools at his disposal. These tools are basically his knowledge of structural theory, the research and development information available and his professional knowledge and experience. However, he is also subject to constraints such as government regulations and client budgets. Having chosen the overall type of structure using his professional knowledge, the designer has to make his detailed design decisions on the basis of a theoretical model coupled with research and development information, codes of practice, etc. The classical way of avoiding the unpleasant events labelled as limit states in is to use the well-known working stress concept. Ultimate load and now limit state concepts are more modern approaches. Here the decisions are based upon a calculation procedural model (cpm) which is usually the combination of elastic theory or plastic theory, with research and development information often distilled by research workers and various committees into recommended procedures.

Table 1.1. Some causes of structural failure.

| Limit states | Overload: geophysical, dead, wind, earthquake, etc.; man-made, imposed, etc. |

| Understrength: structure, materials, instability |

| Movement: foundation settlement, creep, shrinkage, etc. |

| Deterioration: cracking, fatigue, corrosion, erosion, etc. |

| Random hazards | Fire, floods, explosions: accidental, sabotage earthquake, vehicle impact |

| Human-based errors | Design error: |

Next page

David Ian Blockley is an Emeritus Professor of Engineering at the University of Bristol, UK. He was born in Derbyshire, England, in 1941. He graduated from the University of Sheffield in 1964 and gained his PhD there in 1967. For 2 years, he was a Development Engineer with the British Constructional Steelwork Association in London working on design development. In 1969, he became a Lecturer in Civil Engineering at the University of Bristol, was promoted to a readership in 1982 and a personal Chair in 1989. In the same year, he was appointed Head of the Department of Civil Engineering, University of Bristol until 1994 when he was elected Dean of Engineering at the University of Bristol from 1994 to 1998. He was reappointed as the Head of Civil Engineering in 2002 until his retirement in 2006.

David Ian Blockley is an Emeritus Professor of Engineering at the University of Bristol, UK. He was born in Derbyshire, England, in 1941. He graduated from the University of Sheffield in 1964 and gained his PhD there in 1967. For 2 years, he was a Development Engineer with the British Constructional Steelwork Association in London working on design development. In 1969, he became a Lecturer in Civil Engineering at the University of Bristol, was promoted to a readership in 1982 and a personal Chair in 1989. In the same year, he was appointed Head of the Department of Civil Engineering, University of Bristol until 1994 when he was elected Dean of Engineering at the University of Bristol from 1994 to 1998. He was reappointed as the Head of Civil Engineering in 2002 until his retirement in 2006.