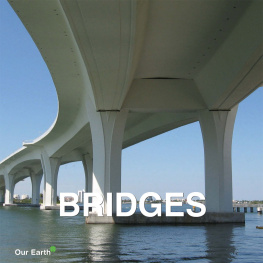

The Confederation Bridge linking Prince Edward Island with mainland New Brunswick, Canada. The bridge was completed in 1997 and with a length of nearly 13 km is the worlds longest bridge over ice-covered water. The bridge is of post-tensioned concrete box-girder construction and undulates dramatically to incorporate 60 metre high navigation arches.

Contents

Great cities are built on great rivers and so, sooner or later, great bridges arise bridges that not only connect and transport but also that play key roles in creating and defining the character, nature and aspirations of the city. Bridges, among all their many attributes, are incomparable place-makers, man-made landmarks that vie with the memorable works of nature. This is most obvious in cities and towns, but is also the case in more remote places where so often it is bridges that excite, that stir the imagination, as they soar above chasms and canyon, knife across vast tracts of water as they dare and achieve the almost unimaginable.

Humanitys inventiveness and structural ingenuity in the creation of bridges, in the evolution of structural systems, in the utiliz ation of technology and materials, is on a par with the engineered excellence of the Gothic cathedrals of medieval Europe. Great bridges and great cathedrals both express in the most sublime manner possible the aspirations of their age, of the civilisation that built them. In Europe and America the genius of bridge building was in the past expressed most forcefully in mighty works, especially by the great railway bridges of the th century utilitarian objects of supreme daring, forged of wrought-iron, steel, masonry in sweat and blood that in the perfection of their function and their fitness for purpose achieved poetic beauty.

Now in the early st century there are few structural restraints that can stymie bridge-builders, there is little that engineers dare not aspire to, little that they cannot achieve. This has become the age of the mega-bridge where boundaries of ambition and scale are being regularly extended through ever growing technological prowess. This is impressive with unprecedented structures being realised. But often these mega-scale solutions are formulaic. Now, in many ways, the outpouring of ingenuity and creativity that distinguish the best bridges of the past is found not in huge creations but in smaller bridges where the challenge is not so much to achieve a crossing on an heroic scale but to do so in a manner that is consciously intended to delight and to give a place identity. In parallel to the rise of the mega-bridge is the evolution of the gem-like, small-scale bridge often only a pedestrian bridge such as the Gateshead Millennium Bridge in England that functions not just as a route but also as a work of art as a creation that provides a promenade, that grants character, distinction and sense of place.

This book is a very personal journey into the world of bridges. I focus almost exclusively on those Ive seen and experienced and so, naturally, the text dwells on those that exist rather than on great bridges that are no more, like Robert Stephensons seminal Britannia Bridge, Wales of 1846 - that has been largely rebuilt and altered out of all recognition. This means, of course, that virtually all the works described can be seen and enjoyed by all who read this book and who like me are always thrilled and stirred by the sight of a good bridge.

Dan Cruickshank

August 2010 .

Always it is by bridges that we live.

Philip Larkin, Bridge for the Living

From earliest times, mankind has built bridges, and still today bridge construction remains heroic, the most absolute expression of the beauty and excitement invoked by man-made constructions that are practical, functional, and fit for their purpose. Bridges that are leaps of faith and imagination, that pioneer new ideas and new materials, that appear both bold and minimal when set in the context of the raw natural power they seek to tame, are among the most moving objects ever made by man. They are an act of creation that challenge the gods, works that possess the very power of nature itself. They are objects in which beauty is the direct result of functional excellence, conceptual elegance and boldness of design and construction.

Like most people, I am addicted to bridges to their raw, visceral punch, to their often astonishing scale and audacity, enthralled by their ability to transform a place and community and amazed by the way a bold bridge can make its mark on the landscape and in mens minds, capture the imagination, engender pride and sense of identity and define a time and place. A great bridge one that defies and tames nature becomes almost in itself a supreme work of nature.

Bridges embody the essence of mankinds structural ingenuity, they show how nature can be tamed by harnessing nature, how mighty chasms and roaring waters the very embodiment of natural power and grandeur can be spanned by utilizing the structural forces and principles inherent in nature; bridge design demonstrates with startling and dramatic clarity the structural potential of different materials and how these materials can be given added strength through design, through the use of forms that work in accordance with the structural laws of nature. For example, stone can be given additional load-bearing capacity and be used to bridge wider spans by being wrought to form well-calculated arches, and wood and metal can achieve great spans if used not as simple beams but when fabricated to form lattice-like, triangulated, trussed structures, where load-bearing capacity comes not through mass but from thoughtful engineering.

The most thrilling bridges are, in many ways, those not enhanced by superficial or extraneous ornament or cultural references. What moves and impresses is their honest expression of the materials and means of construction their only ornament is a direct result of the way in which they are built and perform. A great bridge has an emotional impact, it has a sublime quality and a heroic beauty that moves even those who are not accustomed to having their senses inflamed by the visual arts.

Bridges are a great paradox, they not only use nature against nature, but magically the best examples do not defeat or damage nature but enhance it, and, in ways that are sometimes hard to fathom, achieve a deep harmony with their surroundings. For these reasons bridges have captured the imagination of people through the ages and now they are the only large-scale and radical examples of modern design and construction that the public generally applaud. All can see that bridges stand for something most significant, for the indomitable human spirit, the love of daring and of challenge, the power of invention.

Bridges, of course, inhabit worlds way beyond the merely physical and visual. Having excited human imagination they have, for centuries, possessed a powerful symbolism. They have been seen as links between this world and the next, as symbols of transition, and as metaphors for life and death on earth, and of the journey of the soul to the afterlife the means of crossing the great divide. This symbolism and fancy have, occasionally, been reinforced by fact, for some bridges have, quite literally and rivetingly, been bridges between worlds and have possessed almost more meaning than physical substance. For example, the stone-arched Bridge of Sighs in Venice, built in 1602 by Antonio Contino (who had earlier worked for his uncle Antonio da Ponte on the Rialto Bridge, ) that formed a covered way between the interrogation rooms in the Doges Palace and the adjoining prison. It has long been assumed that the small windows in the bridge offered convicted prisoners their last view of Venice or of life. The idea of the bridge as a metaphor for transition or for a journey of the spirit seems universal. In fifteenth century Peru, the Inca saw the rainbow as a bridge between their homeland and heaven, while some of the indigenous people of Australia conceive of the link between worlds taking the form of the vast, arching and bridging body of the rainbow serpent, a creature as it happens that is most similar to the Lebe snake, the bridge-like ancestor of the Dogon people of Mali, Africa.

Next page