In loving memory of my mother,

Frances Ribowsky

CONTENTS

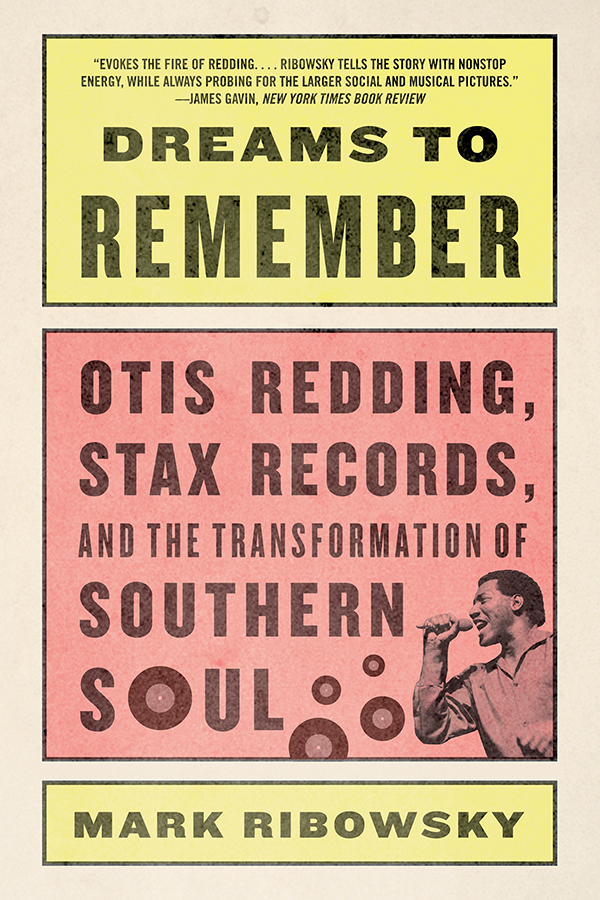

I f one looks back at the 1960s through a high-magnification lens and with a healthy sentience of culture and the innate role popular music played within it, two songs might very well reveal everything there is to know about the nature and meaning of that decade. Indeed, within this books covers, the argument can and will be made that these two recordingsAretha Franklins cover of Otis Reddings Respect in the spring of 1967, and Reddings posthumously released (Sittin On) The Dock of the Bay early in 1968rise above all other three-minute, 45-RPM, vinyl-backed symphonies derived from those turbulent and terrifying times. One reflects the need for generational outcasts to find a place among new societal norms, the other the need to find sanctuary in that new place.

Unlike Sgt. Pepper/Incense and Peppermints entreaties to tune in and drop-out, or Blowin in the Wind/Eve of Destruction vetoes of hubristic war and group-think intolerance, Respect and Dock of the Bay provided the thread and threnody of the most uproarious and portentous of decades. Performed not incidentally by the king and queen of soul, they helped seed social change that, alas, never came to fruition in Reddings time and was in fact smacked down metaphorically in the decades dying days by the literal deaths on a motel balcony in Memphismere blocks from where Otis Redding recorded most of his songsa hotel kitchen in Los Angeles, and a speedway in Altamont.

Both of these priceless, timeless, chart-topping capsules of an America at war with itself, were so perfectly timed, just months apart, that they stand as a cause and effect. With them, Otis Redding found his own calling, not as musician, but as a prophet and a poet. In other words, Reddingsimply the most overpowering and electrifying soul stage performer of his time, and just as profound an influence behind the scenesbecame the nerve and conscience of soul music about to be fully integrated into the rock and roll arc.

Respect was clearly much larger in overall meaning than its individual verses, which were meant to add dynamite to the emotional ammunition of Reddings raspy, open-wounded wailing, which was perfectly coordinated with the edgy call-and-response horn blasts and soul-deep back beat that stamped the jazzy, sweaty funk of the Memphis sound. But because it was recorded in 1965, the year of the Voting Rights Act, a year after the Civil Rights Act, and two years after the March on Washington, such a demand by a black manto be appreciated for his hard work and the sacrifices he madetranscended the songs narrow trope of a man looking to be respected by his woman after a hard day. Civil rights anthems were not necessarily tightly and obviously focused on the cause; during the march, when Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his I Have a Dream peroration, Little Stevie Wonders raucous Fingertips (Part 2) was the top song on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, a major crossover step for a black artist, and for no easily discernible reason was a sort of quasi-anthem for the event, wafting as it did on transistor radios through the crowds on the Mall between the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial.

In the same way, the songs of Motown and Stax/Volt were heard often on Armed Forces Radio in the jungles of Vietnam, offering American GIs who didnt want to be there the familiarity of life back home, a hint that such music soldered civil rights to anti-war protests and another prompt to question why they were indeed there.

REDDINGS RESPECT, cut on July 9, 1965, in a converted movie theater in Memphis that would become the center of popular music a few years later, was just another day at the office for the staff at Stax. It was produced by Steve Cropper and anchored by the best house band known to man, the inimitable Booker T. and his MGsCropper, Donald Duck Dunn, Al Jackson, and their leader, Booker T. Jones. When it was released on August 15, 1965, the song only made it to number 35 on the pop chart. Yet its impact was felt within the well of black pride. It was Top 5 on the Black Singles Chart, a category soon changed in favor of the more politically correct R&B Chart. But, like Fingertips (Part 2), its grooves and that sweeping title of pride against prejudice were important cultural markers, for inner-city America a command to keep fighting the de facto segregation of Jim Crow, to not sit at the colored lunch counter or follow the signs to the Colored Only bathroom.

Still, its one of the threads of the Redding story that he would nurse his aversion to being labeled and interpreted instead of merely heard. Yet even neutrality was reflexively criticized by some in a black cognoscenti impatient to present their stars as patriotic equals of white performers who knew enough to pay lip service to men in war. Why wont top Afro-American entertainers go to Vietnam and entertain the troops there? Its a sore subject, Needless to say, standing against the war would have been far out on a limb, indeed.

When Otis in 1965 cut a cover of Sam Cookes posthumous 1964 release A Change Is Gonna Comeas brilliant a landmark as ever there was among sixties soul message songsReddings intent was less urgent than Cookes, who came of age in the 1950s when black men were paid not to make a ruckus anywhere but onstage. Cookes conscription of protest into an ingredient of his bombastic stage show was enough of a leap forward. Change wasnt here, but it was going to comein time. For Reddings prime influencesLittle Richard and James Brownthere never was such a revelatory transition; indeed, Browns political coming-out (as opposed to his racial coming-out in such anthems as Say It Loud Im Black and Im Proud) was, confusing to many, as a Republican , his statement made almost tragicomically, wearing a flag-draped jumpsuit while performing Living in America.

It was only logical, then, that Reddings version of Respect was not as successful or earthmoving as Aretha Franklins cut, arguably one of the greatest recordings in modern music history. Although each version was recorded under entirely different conditions and protocolsFranklins a technical marvel made in New York under the watch of uber engineer Tom Dowd, and Reddings in Memphis, the product of nearly impromptu jams, one or two takes, all liveboth had the benefit of some of the most talented session musicians ever born.

But Aretha also had the benefit of two more years of cultural give and the progression of inner-city norms into a hip white society that was just now learning to respect the talent and contributions of black men and women. Redding had provided the groove and beat of a song so infectious it has been covered by literally dozens of artists from every idiom. In the maw of the 60s, it could be interpreted any number of waysindeed, when Franklin verbally spelled out R-E-S-P-E-C-T , she also had the advantage of a yearning for respect that was being echoed by a fledgling womens rights movement. And when she told her man, Take care... TCB, a line she added to the song, this command from a strong woman to take care of business cut in a million directions: political, sexual, generational, and all in between. Little wonder that Otis, as ambivalent as he was about being one-upped on his own song, began using the line in his own renditions of it.

Jerry Wexler, the grand doyen of Atlantic Records soul music empire, produced the Franklin version, a symbolic and sonic connection between the Memphis sound and the company that muscled in as its Northern overlord and creative partner. He once remarked that Respect was global in its influence, with overtones of the civil rights movement and gender equality. It was an appeal for dignity. In a great leap forward for the songs marketability, such an appeal, and the impudence of a woman making it, broadened the implicit significance of the deceptively ingenuous lyrics. As a result, Wexler and Franklin took the song to number 1 on both the pop and R&B charts. This meant that even assassination and conditioned opposition could not stop what was now the developing lay of the land in American culture.

Next page