This Is a Borzoi Book Published by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Copyright 1993 by Jerry Wexler and David Ritz

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Owing to limitations of space, acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published material will be found following the Index.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wexler, Jerry.

Rhythm and the blues : a life in American music / Jerry Wexler and David Ritz.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-81900-0

1. Wexler, Jerry. 2. Sound recording executives and producersUnited StatesBiography. I. Ritz, David. II. Title.

ML 429. W 4 A 3 1993

781.643092dc20

[ B ] 92-31704 MN

v3.1

For Ahmet Ertegun

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

F or love and support, we would like to thank our familiesLisa Wexler, Paul Wexler, Roberta Ritz, Alison Ritz, Jessica Ritz, and especially Jean Wexler, for her invaluable editorial input at a critical juncture.

Were especially grateful to our editor, Gary Fisketjon, who made this project possible, and to Pete Hamill and Stanley Booth, who (each separately) touted the idea of a Wexler story to Fisketjon. Thanks to Toby Byron for suggesting the formation of the Wexler/Ritz team, to the Aaron Priest Literary Agency, and to the many interviewees, including Ray Charles, David Fathead Newman, Hank Crawford, Renee Pappas, Cy Ampole, Berry Gordy, Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller, David Geffen, Ahmet Ertegun, Arif Mardin, Dickie Kline, Etta James, Mark Myerson, Steve Paley, soul scholar Herb Boyd, Tom Dowd, Stanley Booth, Barry Beckett, Jimmy Johnson, Donnie Fritts, Rick Hall, Duck Dunn, David Hood, Roger Hawkins, Spooner Oldham, Jerry Greenberg, Milt Gabler, Connie Hillman, Alan Pariser, Earl McGrath, Shirley Aprea, Tommy Aprea, Lisa Wexler, Paul Wexler, Bonnie Bramlett, Mac Rebbenack, Lorraine Rebbenack, Barry Goldberg, John Bryant, Ray Baradat, Barry White, Isaac Hayes.

THE

MAN

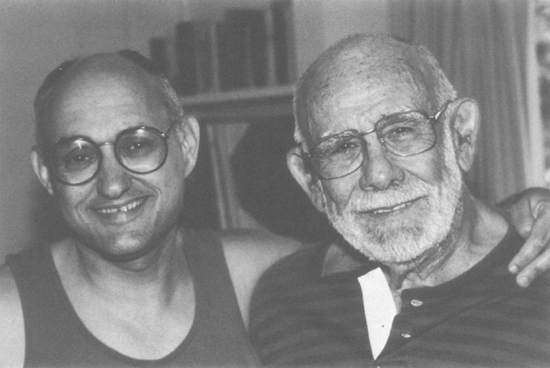

A t seventy-five, Wexler is still a holy terror.

He runs around like an impatient kid, shopping for baby white eggplants at distant farm stands, booking acts for the local jazz association, talking on the phone to musician pals, celebrating the latest Hank Crawford or T-Bone Walker reissues, making Benny Goodman tapes for his butcher, dominating the dinner conversation with war stories of song pluggers and smash records. His eyes twinkle; his fingers nervously smooth over his white beard. The mind is racing. Compulsive, cunning, extravagantly verbal, he stays two beats ahead. His rapid-fire speech blends a promoters hype with a scholars precision, his lexicon a mixture of the mean streets and the graduate library. When you question a word he usessay ratiocinationcomplaining that even an educated reader might balk at the meaning, he fires back in double-thick, unyielding New Yorkese, Send the fuckers to the dictionary!

Wexler loves language. What falls from his mouth arent merely words but self-styled music, now harsh, now harmonious. His ego, fierce and battle-ready, has a soft underside. Hes one of those tender tough guys. He relishes a good fight. His domain stretches from early swing to surrealism, from John OHara to Anita Brookner, and a litany of cultural stops in between.

Of his several obsessions, food is among the strongest. Ingredients must be fresh, wholesome, and handpicked; every meal must be perfect. As he once produced record sessions, he now produces lunches and dinners, supervising his Asian cook with the same firm finesse with which he supervised Dire Straits.

Over dessert, hes still going strong. He expounds on the greatness of clarinetist Pee Wee Russell; he analyzes the ironies of Magritte; he asserts his agnosticism, insisting on empirical rationalism. He wants you to listen. He wants you to fall in love with him. If his points of view are more papal edicts than opinions, his ability to laugh at himself saves the day. His energy is inexhaustible.

For years hes been waiting to tell these tales, to capture your attention and charm you into listening. His need to explain himself, to share his extraordinary adventures, is overwhelming. He demands attention. In his splendid digs in Sarasota, Florida, or East Hampton, New YorkI live like King Farouk! he exclaimshis enthusiasm is contagious, his passion irresistible.

You give in. You sit and listen to the stories of New York in the thirties, the wonders of the Depression-era pool halls, the angst of Dad, the drive of Mom, the joys of stickball, the discovery of sex and jazz, the Army and the forties, the Brill Building Broadway buzz of the fifties, crude gangsters and crafty geniuses, his partnership with the Ertegun brothers, his soul-music talent hunts through the South, his forays into New Orleans and Nashville, Austin and Muscle Shoals, his pioneering work with Joe Turner and Ruth Brown and Ray Charles, his molding of Aretha Franklin, his nights with Willie Nelson and Bob Dylan, his method of buying in, making millions, cashing out, watching record labels evolve from seat-of-the-pants independents to massive conglomerates.

These stories are his life, a singular journey through the musical culture of our times.

David Ritz

TIME ON

IN

BULLSHIT

ALLEY

W ashington Heights was a lower-middle-class enclave of Jews, Italians, Irishwage earners, civil servants, and small businessmen. We moved there when I was six. West of St. Nicholas Avenue was the Hudson River, buttressed by the imposing Palisades on the Jersey side. The streets in between had apartment houses ranging from simple five-story walk-ups to elegant buildings with doormen and elevator operators. East, towards the Harlem River, were Audubon and Amsterdam avenues, where many of the folks were on home relief, the welfare of its day. There were very few cars, and north of 184th Street dirt roads ran into vast woods. From Riverside Drive down to the banks of the Hudson was a verdant jungle, a made-to-order wilderness for kids. Although strange objects came drifting by in the Hudson, the water was relatively clean, and its treacherous currents bred a bunch of damn good swimmers.

But it was an indoor sport that made Arties poolroom the locus of my childhood. As in the recording studiothe most important arena of my adulthoodthe poolroom was where lessons were learned, characters intermingled, battles won or lost. The poolroom was it.

Arties had me enthralled. I couldnt stay out of the place, perched on the second floor of a double-story buildingcalled taxpayers back thenon the corner of 181st Street and Bennett Avenue in Washington Heights. By my early teens, I was already something of a honcho. It was 1930, and the Depression was deep, hard, and dirty; anxiety lurked everywhere except in the imagination of a kid excited by the wonders and challenges of the streets. Robust and restless, I was considered gutsy by those I respected most, the guys in the poolroom.

Artie Goodman, the owner, was a tough guy himself. Bald as a cue ball, his face framed by glasses thick as the bottom of a Coke bottle, Artie brooked no nonsense. Given any shit, he might, for example, hook his middle finger in the corner of the miscreants mouth and ripeither that or throw the troublemaker down two flights of ladder-steep stairs.