Preface

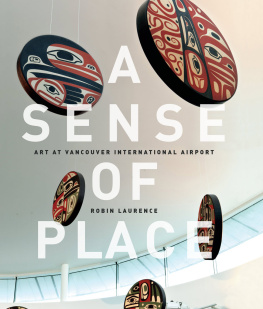

T he last time I saw Bill Reid was in 1994. My book, Between Two Cultures: A Photographer among the Inuit, had just been published and I was speaking to a group of businessmen on the top floor of the Hotel Vancouver. Accompanied by his wife Martine, Bill sat close to the lecture podium. I knew who Bill Reid was I had heard him give a lecture at the University of British Columbia in the late 1970s. During his talk, Bill had worn his knowledge of Haida art and culture lightly. I had been impressed by his modesty, manifested in his attempt to diminish the role he had played in what many people have called the revival of Northwest Coast Native art. Yet it was obvious to me that beneath his offhand manner lay a breadth of knowledge about and a commitment to Native art and culture. I did not see Bill Reid again until a mutual friend invited me to dine with him in the summer of 1990. By this time he had overseen the carving of Raven and the First Men, launched his canoe Loo Taas, and was in the midst of his largest commission, The Spirit of Haida Gwaii.

Long before I embarked on my research for this book, I knew that Bill Reid was not the sole architect of the so-called renaissance of contemporary Native art. As a cultural historian, I suspected that his public persona as a Haida Indian was as much a product of journalists, art patrons, museum curators, and others associated with the non-Native establishment as of Bill Reid himself. At the same time, I had been bowled over by works like Raven and the First Men. What other sculpture in the history of public art in Vancouver has so excited schoolchildren that they shout, as they enter the Museum of Anthropology: Wheres Bill Reids raven? Or prompts adults to compare Raven and the First Men with Michelangelos Piet, seen on their summer vacation in Rome?

I also knew that Bill Reid was not the only major figure in the history of postWorld War II Northwest Coast Native art. During the mid-1950s I had observed the Kwakwakawakw artist Mungo Martin (Nakapenkum) both restoring and creating totem poles in the carving shed adjacent to the Provincial Museum in Victoria. As an even younger child, I had attended a potlatch in the Coast Salish community house at Cowichan Bay on the southeast coast of Vancouver Island. The cedar-scented smoke, the masks and rattles, and the mournful song of the elders, who had beat out the steps for the dancers on their drums, had left no doubt in my childhood mind that Indian culture was very much alive.

These early experiences, along with my later contact, during the course of researching my biography of Emily Carr, with the Git x san and Nisgaa peoples living on the Nass and Skeena rivers, with the Nuu-chah-nulth in Ucluelet, and with the Haida on the Queen Charlotte Islands, made me question the prominent role that Bill occupied in the story of Northwest Coast art. I began to wonder if revival and renaissance were the right words to describe the process, and whether continuation would not have been a more accurate word when talking about what took place in British Columbia during the 1950s and 1960s.

I would like to have had Bills response to my lecture on Inuit photography that autumn day in 1994. After all, the central theme of my talk the ways in which photographic images of indigenous peoples have been used by non-Natives was of interest to Bill Reid. He did say something when, at the end of my lecture, I walked over to where he was sitting. I bent my head close to his, trying to understand. Bill repeated his effort. But it was no use. Whatever he was struggling to say was incomprehensible to me, as it was to Martine Reid. Parkinsons is a cruel disease; it not only erodes mobility, it robs its victim of speech. The sonorous baritone voice that had brought the evening news to thousands of Canadians across the country had been reduced to a rasping, unintelligible whisper.

I did not think much about Bill Reid again until the spring of 1998. Opening my e-mail one morning in my college rooms at Cambridge University, I was confronted with a number of messages from friends. They all informed me that Bill Reid had succumbed to his long battle with Parkinsons disease on March 13.

Three days after his death, Globe and Mail writer Miro Cernetig set the stage for the accolades that followed. Reid had saved an artistic tradition that was in danger of being lost.

A week later, news of Bills death made it to the obituary pages of the New York Times.

Reading the obituaries and the tributes made me feel increasingly uneasy about the reporting in the press. Much of it was inaccurate. Writing in the Globe and Mail, David Silcox mistakenly credited Bill with being the first artist within living memory to raise a large totem pole and to carve a dugout Virtually every other reporter ignored the earlier achievements of artists such as Mungo Martin and his wife, Abayah; Jimmy Seaweed; Ellen Neel; John Cross; Claude Davidson; and many others who were active long before Bill Reid appeared on the scene. The public was being given a skewed sense of the past.

Much was left unsaid. No one mentioned the extent to which Bills work drew on western aesthetics. No one adequately explained why Bill and his work meant so much to the Canadian people. Or how he came to play such a pivotal role in the Native art world. Or how he got to where he was by the end of his life. Or why he was not accepted into the Native and non-Native establishments earlier in his career. Or, finally, why his acceptance in and discovery by the Native and non-Native communities became a major theme in Bill Reids story of struggle.

As I sifted through the obituaries, I wondered why so many people, from collectors, museum curators, gallery dealers, art critics, and Native rights activists to the public in general, had exaggerated the uniqueness of Bill Reid and misrepresented his achievements in ways that revealed more about themselves than about the artist. Was it simply economics? For surely the value of Bills work had increased now that he was dead. Did his journey of self-discovery resonate with a society whose identity has always been in a constant state of becoming? What was the evocative power of Bills art: the exquisitely crafted gold bracelets and boxes, the massive totem poles and canoes, the argillite carvings, the prints and his writings? What was the secret to the way Bill projected himself his charisma, his partial Native ancestry, and his heroic struggle against a debilitating disease? Whatever it was that made the Canadian public mourn the death and celebrate the life of Bill Reid, I was intrigued.

When I returned to Canada in June 1998 at the end of the academic year, I made it my business to find out who this man really was and why he and his art had caused so many people to mourn his passing. A flyer issued by the Museum of Anthropology, announcing its acquisition of Bill Reids papers, gave me some hope. The announcement appeared to indicate that his archive would be made accessible to scholars. When I asked to consult the collection, however, an archivist told me that his heirs had withdrawn it from the museum.