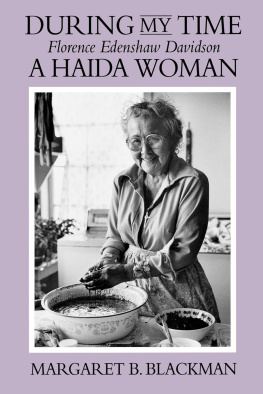

DURING MY TIME

Florence Edenshaw Davidson

A HAIDA WOMAN

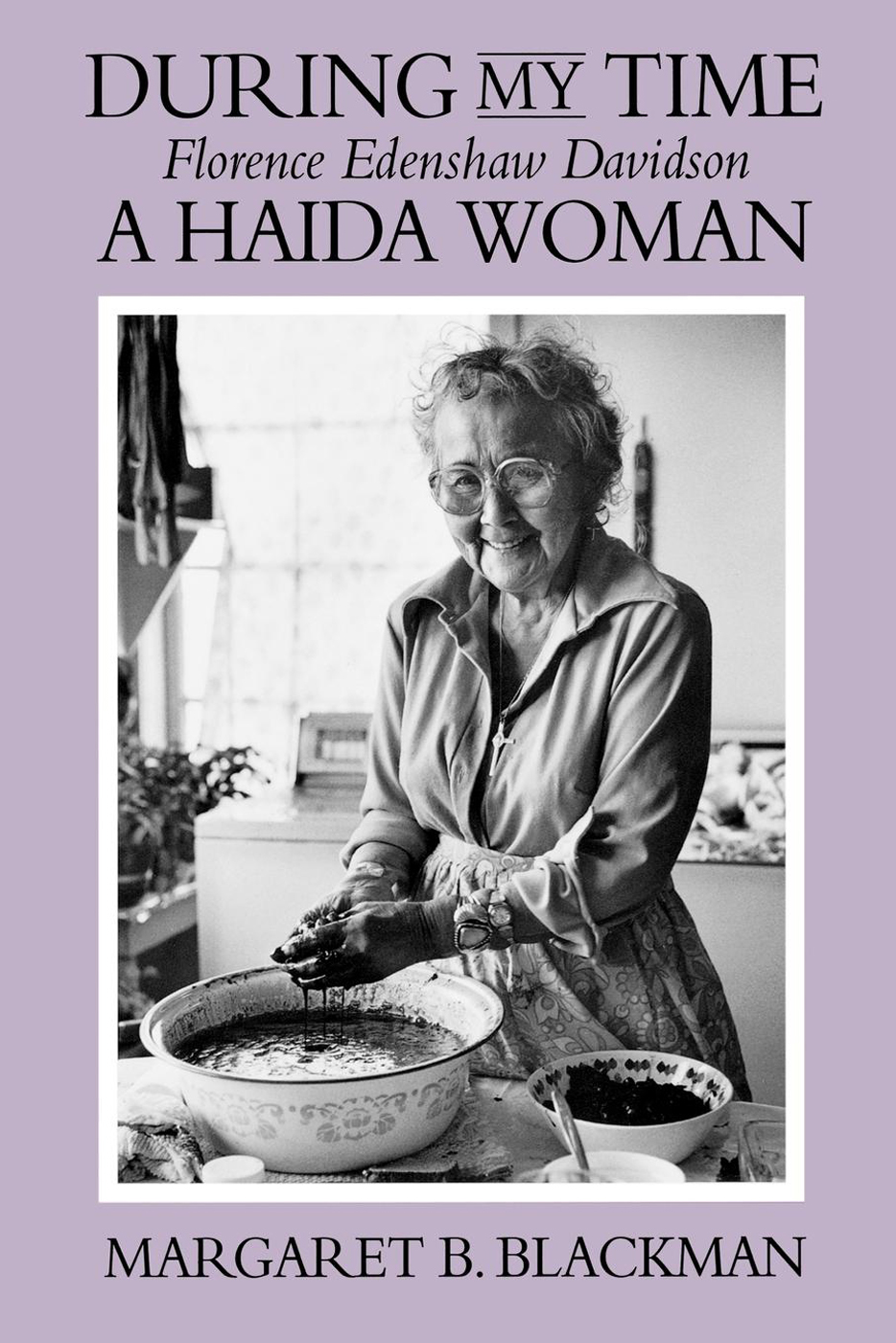

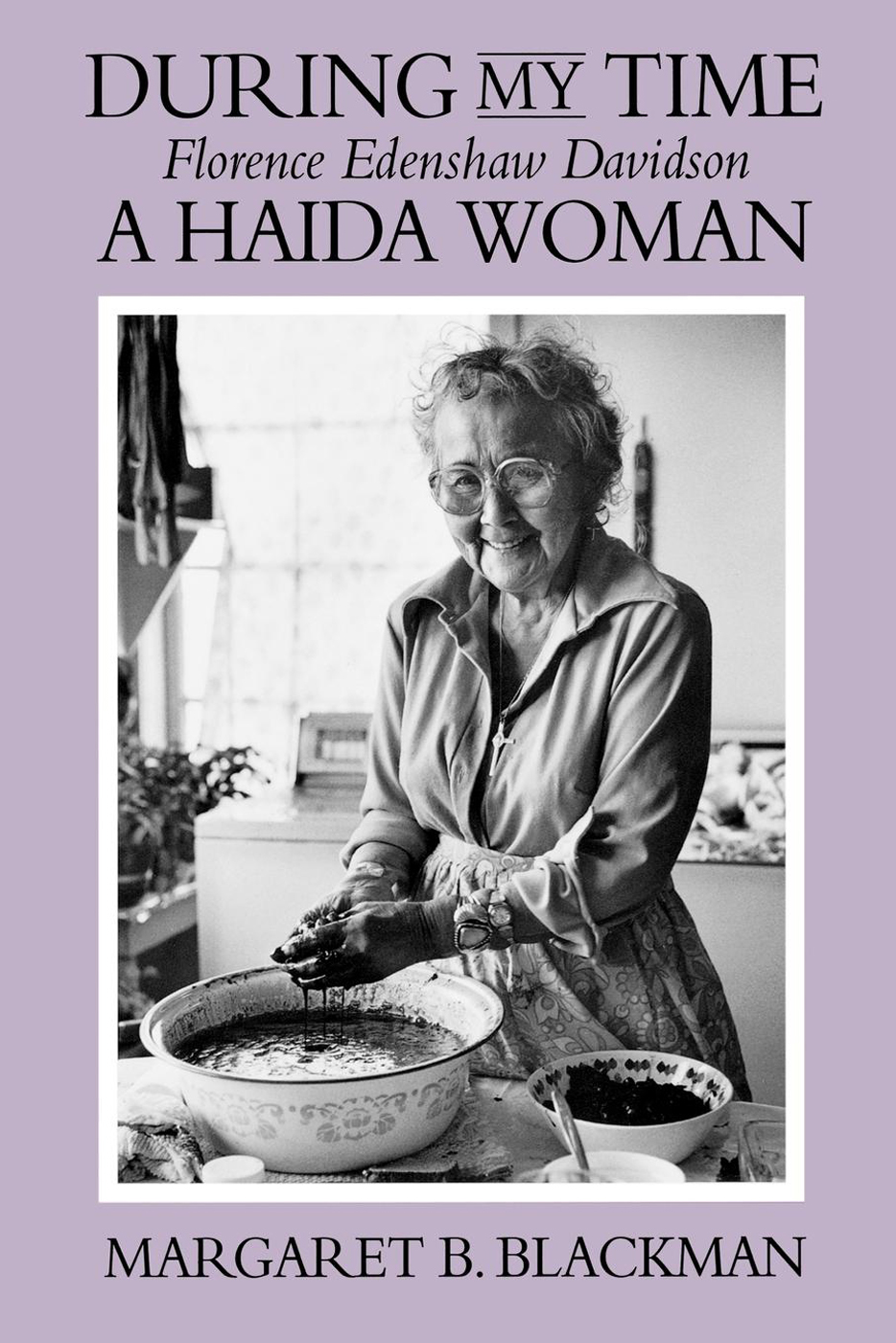

Florence Davidson, 1980

DURING MY TIME

Florence Edenshaw Davidson

A HAIDA WOMAN

Revised and Enlarged Edition

Margaret B. Blackman

University of Washington Press

Seattle and London

Douglas & McIntyre

Vancouver/Toronto

This book was published with the assistance of a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 1982 by the University of Washington Press

First paperback edition, 1985

Fourth printing, 1990

Revised edition copyright 1992 by the

University of Washington Press

Printed in the United States of America

12 11 10 09 08 07 06 8 7 6 5 4

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or, in Canada, a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

University of Washington Press

PO Box 50096

Seattle, WA 98145-5096

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Douglas & McIntyre

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver, BC Canada V5T 4S7 ISBN: 978-0-295-97179-7

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is found at the end of this book.

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and 90 percent recycled from at least 50 percent post-consumer and at least 50 percent pre-consumer waste. It meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

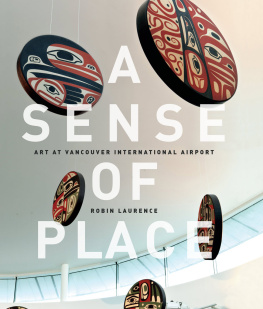

Cover photograph by Ulli Steltzer.

Frontispiece photograph of Florence Davidson by Margaret Blackman.

For her children, their spouses,

and all who know her as Nani

constitute Florence Davidsons first-person account of her long and rich life. The ornament that introduces her narrative is a dogfish shark by her grandson Robert Davidson.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE TO THE REVISED EDITION

Squeezed between hardcover is the text of a life, its beginnings, its turning points, its closure at the time of the telling. It represents in some ways a final statement, an authoritative text on a life lived and recalled, but in reality a life story is never finished with publication. The book presents but one version of the life as told, and the story and the text are further subject to alterations over time as the narrator ages, rethinks, revises, and retells, and as the editor reconsiders the representation of life history material. Such re-examination, in both its affirmation and revision of the original, enriches our understanding of the life history process. At a time when reflexivity, the questioning of textual authority, and close examination of narrative structures direct many anthropological endeavors, new readings of old texts is a critical enterprise. But few anthropological life histories have undergone re-examination to the extent of being issued in second editions.

Within this context, I was motivated to re-examine During My Time. In the summer of 1990, ten years following completion of the manuscript, I sat first with Florence Davidson to record her reflections on her published life story and then with several members of her family to record theirs. My narrative of that research and of the magnificent 95th birthday party fte held for Florence the preceding year comprises the epilogue, One More Time.

An issue central to the writing of that epilogue is the nature of Native American biography and life history today and our unique role as authors/editors of those works. Questions of audience, the politics of cultural representation, and the changing narrative of Native American history are all raised in the re-examination of Florences story and my attempt to update it.

The collaborative nature of life histories from inception to print, especially those from Native North America, is emblematic of the times in which we write and of the larger relationships between the scholarly community and the communities of people we research. Much has been written recently in anthropology of the dispersal of ethnographic authority, the democratization of anthropological research, the blurring of lines between the researcher and the researched.a woman of her time and did it well: she is community-spirited and has tirelessly served her community through her various leadership roles within the Anglican church. She was and continues to be a devout Christian. She raised her children to be prominent and active citizens; she shows, in the Haida way, respect for herself. Florence and her family fulfill their social-ceremonial obligations. And they manage their money well, with the result that very few of their large extended family are on welfare. Florences is the exemplary life, its value enhanced because of her age and the period of history to which her experience reaches.

In a community such as Masset, a life history is never simply the product of two individuals collaboration. Florences account was subject to a number of cultural constraints. Issues of cultural representation and presentation of self are crucial in Northwest Coast societies, with no exception in Masset. Ones prominence and social standing should be apparent, but not through public self-proclamation. It is acceptable to describe the hard work youve always done, but you shouldnt brag about being from a chiefs family, extol your own or your childrens good behavior or accomplishments, or publicly berate someone else, even though in certain circles you may do all these things. Gossip, accusations, commentary on other peoples social misbehavior and stinginess in comparison with ones own exemplariness fill the spaces about the kitchen tables in Masset, but are not fare for public speechmaking, nor for life histories, particularly if the author wishes to maintain good ties in a village where inevitably ones book is read.

Florences own editorial hand in her life history was apparent from the very beginning. I dont tell everythingwhats no good she cautioned, as I noted in the first edition. On more than one occasion, she would instruct me to shut that thing off while she relayed something important that was not to be included in the book. Interviews with her and her family in the summer of 1990 included similar instructions and/or material proffered on tape but off the record. Some reviewers of the first edition of the life history complained about these omissions: The untold stories lie beneath the facts. The main element missing in this life story is conflict (Jackson 1983:56). If we are interested in how people construct their identities and how they tell their stories, we must read the omissions, with the understanding that they, in their own way, also tell the story. On a more operational level, the very kinds of things that lead to lawsuits when biographers transgress agreements with their subjects make the anthropologist at the least an unwelcome

Every life history interviewee obviously edits the telling of his or her story, and consequently every life history is a partial story. But some life stories contain more conflict or seem more candid, less guarded, than others. In some cases the explanations may lie in culturally specific traditions of self-revelation and public discourse, but the reasons may be more blatantly political. In Marjorie Shostaks (1981) popular life history of a !Kung San woman,

Next page