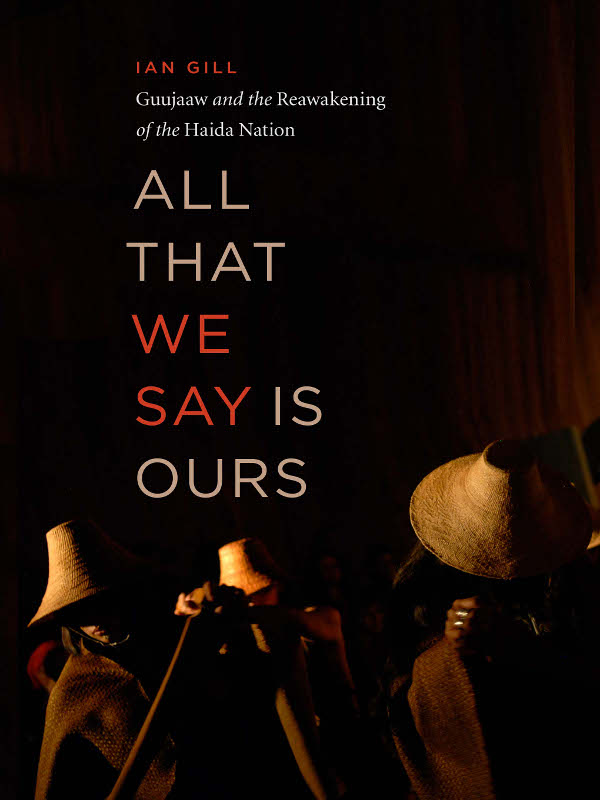

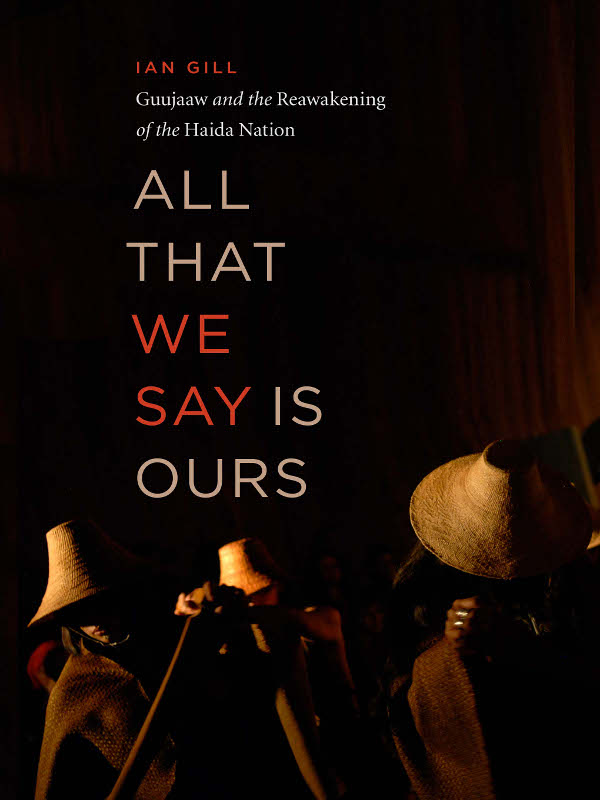

ALL THAT WE SAY IS OURS

Guujaaw and the Reawakening

of the Haida Nation

ALL THAT WE

SAY IS OURS

IAN GILL

Copyright 2009 by Ian Gill

First U.S. edition 2010

09 10 11 12 13 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency ( Access Copyright ). For a copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Douglas & McIntyre

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver BC Canada V5T 4S7

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Gill, Ian, 1955

All that we say is ours: Guujaaw and the reawakening of the Haida Nation / Ian Gill.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-55365-186-4

1. Haida Indians. 2. Guujaaw, 1953. 3. Haida Indians Claims.

4. Haida Indians Government relations. 5. Haida Indians Biography. I. Title.

E99.H2G89 2009 971.1120049728 C2008-908107-2

Editing by Barbara Pulling

Jacket design by Naomi MacDougall

Text design by Ingrid Paulson

Cover photograph copyright Farah Nosh, 2009. The photograph, taken in

Skidegate, Haida Gwaii, in August 2008, is from a performance of Sin Xiigangu

( Sounding Gambling Sticks ), the first play to be written in the threatened Haida language.

The play was performed by younger-generation Haida with the guidance of their elders.

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens

Printed on acid-free paper that is forest friendly ( 100% post-consumer

recycled paper ) and has been processed chlorine free.

Distributed in the U.S. by Publishers Group West

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program ( BPIDP) for our publishing activities.

This book is dedicated to my mother, Jane Fergusson,

for her love of language, and to my late father, Desmond Gill,

for his love of the well-made object.

They became what they beheld.

William Blake

They more than what we are,

Serenity and joy

We lost or never found,

The form of hearts desire,

We gave them what we could not keep,

We made them what we cannot be.

from Statues, by Kathleen Raine

CONTENTS

ONE

THEN AND

NOW

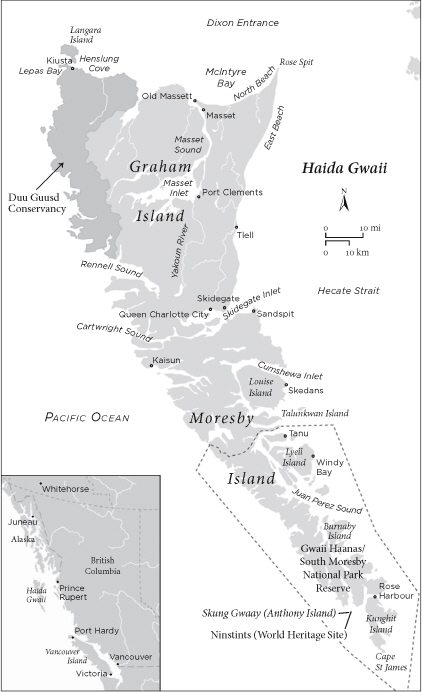

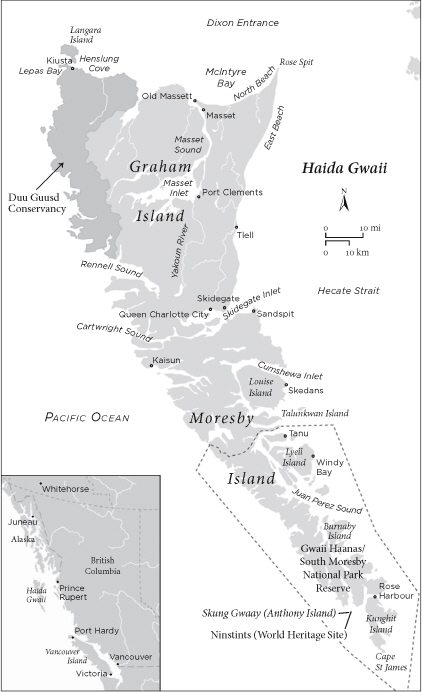

BACK THEN, PEOPLE rounded the point at G aw, or maybe came from out by Yan, and when they entered Masset Inlet there was a long line of totem poles and canoes and house fronts along the inlets eastern shore. On the flood, now as then, the tidal rip adds eight knots or so to your hull speed, so the village goes by pretty fast. The old black-and-white photos show as many as forty totem poles along the shore, more in behind, but there are not so many poles now, no canoes on the beach, hardly any big houses, although the first house you see coming into Old Massett by boat these days is Jimmy Harts Three Rainbow House, and it is a very big house.

It is fitting that Jim Hart has a big house. He is an important chief in these parts, Chief  Idansuu of the Staastas Eagle clan, directly descended from Albert Edward Edenshaw, the name Eden-shaw being as close as the white men came to getting their tongues around the word

Idansuu of the Staastas Eagle clan, directly descended from Albert Edward Edenshaw, the name Eden-shaw being as close as the white men came to getting their tongues around the word  Idansuu, back then.

Idansuu, back then.

Like Albert Edenshaw before him, Jim Hart is a powerful hereditary chief and a prominent Haida artist. This is readily apparent when you come into Old Massett by boat and see not just Jim Harts house but, to the right of it, a totem pole that Hart carved and erected in 1999. Thirty years before, the famed artist Robert Davidson had erected a pole in the village, the first pole raised in Old Massett since the Haida emerged from the silent years and began to find their voice again. A profusion of totem poles has gone up in the village in the decades since. By days end, on this Saturday in August, there will be another pole erected in Old Massett near another big house Christian Whites place, the Canoe Peoples House.

These days most people get to Jim Harts house by road, not by boat. You leave the town of Masset and drive to the village of Old Massett, past Christian Whites house and on down Raven Avenue till you cant go any farther, and thats Jimmys house on the left, before the cemetery.

Inside, there are people working methodically but quickly towards a deadline, because Chief  Idansuu is having a potlatch tomorrow, Sunday, and there is much still to do. Several young Haida apprentices hunch over a long, wide red cedar plank, painting bold ovoid shapes and strong lines in black and red, the traditional base colours of Northwest native art. The fresh lines will need to match up exactly with the board that came before and the one that will come after, twenty-four planks in all. Hart himself is off to one side, carving a cedar helmet, a raven. Two of his children, Carl and his twin, Mary, sit on a couch folding and rolling small hand towels and securing them with decorative ties, then tossing them into a plastic tote. A couple of folks are dragging and stacking endless other totes full of gifts shipped up from Vancouver, while someone else is unloading salmon, lots of salmon.

Idansuu is having a potlatch tomorrow, Sunday, and there is much still to do. Several young Haida apprentices hunch over a long, wide red cedar plank, painting bold ovoid shapes and strong lines in black and red, the traditional base colours of Northwest native art. The fresh lines will need to match up exactly with the board that came before and the one that will come after, twenty-four planks in all. Hart himself is off to one side, carving a cedar helmet, a raven. Two of his children, Carl and his twin, Mary, sit on a couch folding and rolling small hand towels and securing them with decorative ties, then tossing them into a plastic tote. A couple of folks are dragging and stacking endless other totes full of gifts shipped up from Vancouver, while someone else is unloading salmon, lots of salmon.

Over near the windows at the front of the house, Harts oldest daughter, Lia, is bent over an impossibly wide sheet of brown paper, updating a massive genealogical chart that starts, as modern Haida history does, with  Idansuu, Albert Edward Edenshaw, b. ca. 1812, d. 1894. The genealogy is a wonderfully complex thing to behold, charting as it does not just descendencies and gender, but splitting even further into moeties and clan lines, represented by circles and triangles, the geometric shapes and shadings linked by lines in a kaleidoscopic pattern that could be mistaken for a massive board for playing Chinese checkers.

Idansuu, Albert Edward Edenshaw, b. ca. 1812, d. 1894. The genealogy is a wonderfully complex thing to behold, charting as it does not just descendencies and gender, but splitting even further into moeties and clan lines, represented by circles and triangles, the geometric shapes and shadings linked by lines in a kaleidoscopic pattern that could be mistaken for a massive board for playing Chinese checkers.

The Hart house in Old Massett has been abuzz for weeks, but the Hart family has been working towards this weekend for more than a year. Hundreds of hours, thousands of acts small and large, will culminate in Sundays house-front raising and feast. The invitations sumptuously calligraphed cards that announce not one but two feasts this weekend state that Jimmy Harts deadline is one oclock Sunday afternoon. Today, Saturday morning, it seems assured that he will miss his deadline by a goodly margin. There is so much left to do. For one thing, he and his apprentices have to down tools and head off back down the road to witness Christian Whites pole raising, at the other end of the village. Later on, Hart will have to go to Whites potlatch, too.

The joint invitation says that Whites pole will be raised today at one oclock, but he, too, is running a bit behind. A crowd that has swelled to about 300 souls doesnt seem to mind, milling about on a gorgeously bright blue sky day as White and his helpers use a backhoe to dig a hole. The Shark Mother totem pole more than ten metres long, carved with the crests of Whites Yahgu laanas Raven clan, and further adorned with eight copper-coloured shields is missing its crowning piece, a large carved white raven that just now is being painted inside the Canoe Peoples House. The paint is still wet when the raven is brought out to be affixed to the top of the pole. The tenon is discovered to be a bit too fat for the mortise, prompting another short delay as White resorts first to a chisel, then to a chainsaw, to get the piece to fit.

Next page

Idansuu of the Staastas Eagle clan, directly descended from Albert Edward Edenshaw, the name Eden-shaw being as close as the white men came to getting their tongues around the word

Idansuu of the Staastas Eagle clan, directly descended from Albert Edward Edenshaw, the name Eden-shaw being as close as the white men came to getting their tongues around the word