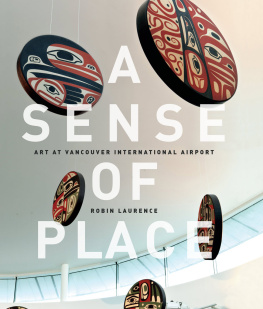

SHAMANS

AND

KUSHTAKAS

NORTH COAST TALES OF THE SUPERNATURALI

MARY GIRAUDO BECK

ILLUSTRATED BY MARVIN OLIVER

To my husband George

Marge and George senior

My children Doug, Steve, Katy

And my sister Kay

In memory of my brothers

Louis, Ernie, and Mike

1991 by Mary Giraudo Beck.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Beck, Mary Giraudo, 1924

Shamans and kushtakas; north coast tales of the supernatural / by

Mary Giraudo Beck; illustrated by Marvin Oliver.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-88240-406-6 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-88240-971-9 (e-book)

ISBN 978-0-88240-966-5 (hardbound)

1. Tlingit IndiansLegends. 2. Haida IndiansLegends.

3. Tlingit IndiansReligion and mythology. 4. Haida Indians

Religion and mythology. 1. Title.

E99.T6B44 1991 90-1295

398.2089972dc20 CIP

Edited by Lorna Price

Cover and book design by Elizabeth Watson

Illustrations by Marvin Oliver

Alaska Northwest Books

An imprint of Graphic Arts Books

P.O. Box 56118

Portland, OR 97238-6118

503-254-5591

www.graphicartsbooks.com

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The stories included in this work, like those in Heroes and Heroines in Tlingit-Haida Legend, have been repeated to me by various Tlingit and Haida friends and students over the forty years I have lived in Ketchikan. Often the tellers related only parts of the stories, or the same stories would be repeated with varying details and outcomes. Therefore, as a guide to retelling the basic story, I made use of several written sources, at the same time weaving in details or outcomes from oral sources. Most frequently used written sources were: Marius Barbeaus Medicine Men on the North Pacific Coast (1953); Viola Garfield and Linn Forrests The Wolf and the Raven: Totem Poles of Southeast Alaska (1956); Aurel Krauses The Tlingit Indians (1956); Frederica de Lagunas Under Mount St. Elias: The History and Culture of the Yakutat Indians (1927); and John Swantons Haida Texts and Myths (1905) and Tlingit Myths and Texts (1909).

Although I am unable to name all those who have told me stories over the years, I offer them my deepest appreciation. I would like to thank those who have helped me in recent years: Gil McLeod, Robert and Ivy Peratrovich, Esther Shea, and Elnore Corbett.

Finally, my special thanks go also to Dolly Jensen and Nancy and Jonathan DeWitt for reading the stories for authenticity, and to Lorna Price for her thoroughness and thoughtful concern in dealing with the text.

M. G. B.

PREFACE

The Tlingit and Haida are the Native Americans who inhabit Southeast Alaska, the panhandle that extends from Yakutat at the north end to Ketchikan at the south. While the Tlingit populate all of Southeast, the Haida have established settlements only on the lower half of Prince of Wales Island, west of Ketchikan the land closest to the northern tip of Vancouver Island, from which they migrated 300 years ago. Living in such proximity naturally led to exchange of ideas and intermarriage, and eventually to the sharing of concepts and legends as well as social structure and practice.

The heroic or wondrous achievements in these tales were used as models for emulation, and the failures as admonitions, by the grandmother of the family to instruct her charges in proper behavior. For she had the duty of transmitting culture, traditions, and customs to the children, while the mothers eldest brother and sister saw to their training in work skills. Both Tlingit and Haida societies were divided into two groups, or phratries, the Raven and the Eagle, and were matrilineal. Membership in a phratry was determined from the mothers line, as were family relationships. Marriage within the phratry was forbidden; an Eagle always married a Raven, and vice versa.

At about eight years of age, a boy went to live with his uncle to learn fishing, hunting, boatbuilding, boating skills, and the proper way to conduct himself as a man. The aunt oversaw the girls upbringing, teaching her household skills and the manners and conduct befitting a young woman, such as listening quietly while men did the speaking and eating small amounts of food in a dainty manner. When the young girl went into seclusion at puberty, her aunt also made sure that she remained in the screened section of the house, seeing and talking only to her, her mother, or a servant, and then only about necessities and instruction for marriage and for wifely duties. The aunt also chaperoned the girl from the time of her seclusion until her marriage, which followed shortly after this period of withdrawal ended. High-caste girls especially were kept from seeing or talking to young men during this time. Marriages for both the young man and the young woman were arranged by the aunt and the uncle on each side.

As tales of wonder and sometimes magic, these stories appeal to readers of various cultures. Their purpose, however, was not only to amuse the listeners but also to dramatize the values and traditions of their society. While undergoing amazing experiences, the characters, in story after story, display traits that the members of the tribe or clan must possess to maintain its integrity and the pitfalls they must avoid to prevent disintegration. The appearance again and again of the same types of characters in familiar activities, as well as the frequent retelling of the stories, provided a unifying force in the community.

Mary Giraudo Beck

Ketchikan, July 1990

INTRODUCTION

Shaman and kushtaka! Both struck terror in the hearts of the Tlingit and Haida people, for both possessed frightening supernatural powers. The shaman, healer and seer, battled the kushtaka (Tlingit for Land Otter Man; in Haida, gageets) for the spirit of a man in danger of drowning or dying of exposure. Stories of kushtaka exploits, though they may no longer evoke the spine-tingling chill of earlier times, still have the power to mesmerize those who hear them.

The Tlingit and Haida universe abounded with spirits, the essences of things animate and inanimate that possessed powers to heal, supply food sources, and maintain harmony with nature. Clouds, mountains, lakes and rivers, trees and plants, birds, fish, and animals all possessed spirits that had to be supplicated or appeased.

In this world, boundaries between the animal and human realms were blurred. The early Tlingit or Haida could hear an omen in the hoot of an owl, or a chilling curfew in the croak of a raven. The land otter, as at home in the water as on land, could conjure in their minds a fearful hybrid being of the spirit world.

The chief spirit was Raven, a trickster, shape-changer, and transformer, who organized the world into its present state, changing some inanimate objects into animate beings, endowing men and animals with particular attributes and roles, gaining for all the blessings of water, fire, and the sun, moon, and stars.

The shaman mediated between this spirit world and the human realm. He was a figure of great power in most Native American cultures. Usually male but occasionally female, the shaman either was called to his role or inherited the gift from a shaman uncle. Through fasting, ritual, and isolation, the shaman put himself in touch with the spirits of the world, became aware of his own failings, and asked the spirits help in bringing his life into accord with nature.