PROUD

RAVEN,

PANTING

WOLF

PROUD

RAVEN,

PANTING

WOLF

CARVING ALASKAS

NEW DEAL TOTEM PARKS

EMILY L. MOORE

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

Seattle

Proud Raven, Panting Wolf was supported by a generous donation from Jill and Joseph McKinstry.

| This book is made possible by a collaborative grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. |

| Additional support was provided by the Tulalip Tribes Charitable Fund, which provides the opportunity for a sustainable and healthy community for all. |

| Publication of this book has also been aided by a grant from the Wyeth Foundation for American Art Publication Fund of the College Art Association. |

Copyright 2018 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Cover and interior design by Katrina Noble

Composed in Minion Pro, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

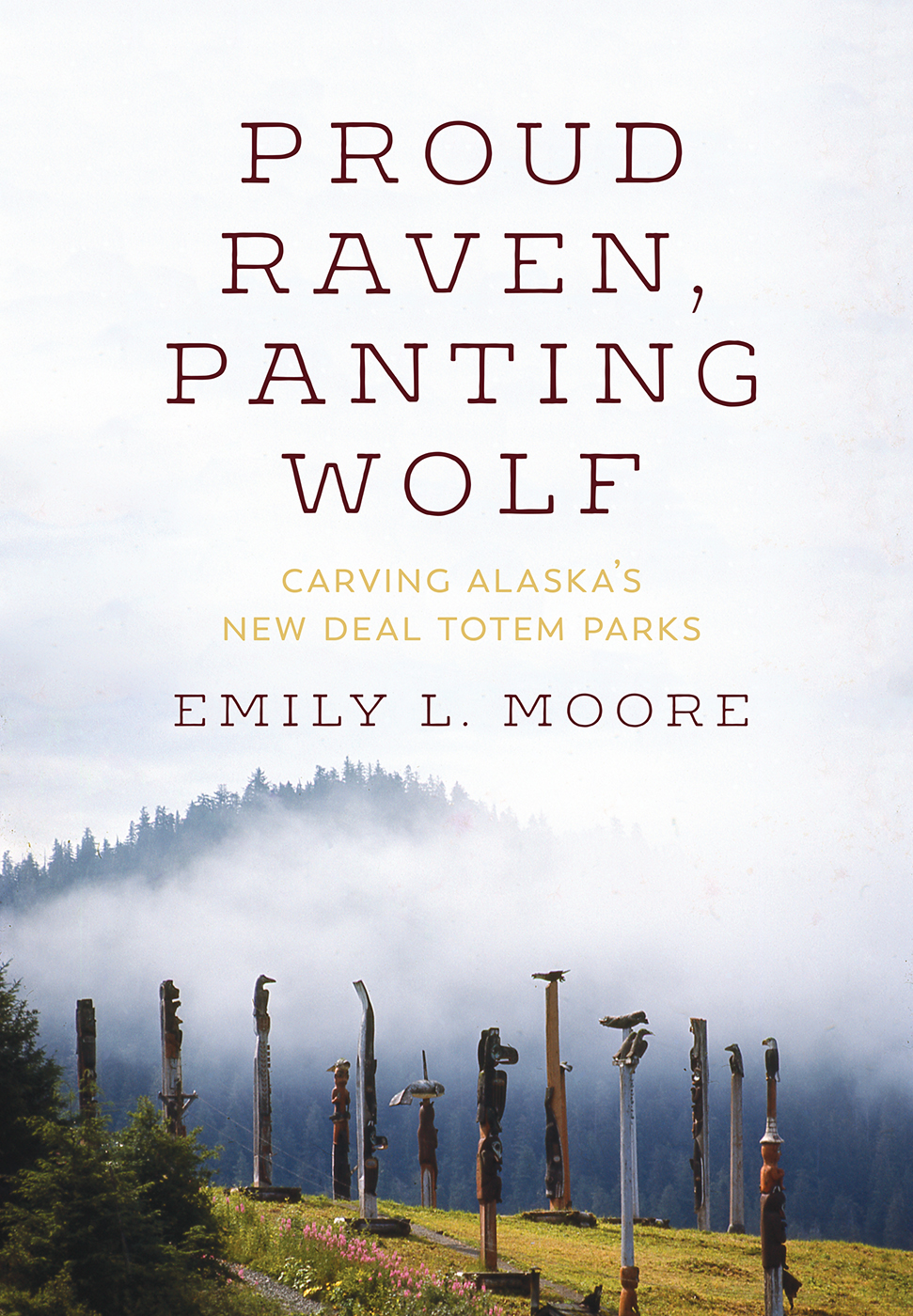

COVER ILLUSTRATION: Klawock Totem Park, 1966. Photograph by Adelaide de Menil. Courtesy of the Bill Reid Centre at Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada.

FRONTISPIECE: US Forest Service officials at Old Kasaan village, 1938 (detail). Photograph number 035-TA-14, Records of the Civilian Conservation Corps, 19331953, Record Group 35, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

All US Forest Service photographs included in this book are in the public domain and cannot be copyrighted.

22 21 20 19 185 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA ON FILE

ISBN (hardcover): 978-0-295-74393-6

ISBN (ebook): 978-0-295-74394-3

CONTENTS

PREFACE

DEEP CARVING

Claude Mijuu Morrison is ninety-nine years old when he watches his grandsons raise a totem pole in the Hydaburg Totem Park, which he helped build in the 1930s (). He sits on a folding chair in the park near a neat row of totem polesmany of them shedding paint after decades in Southeast Alaskas notorious rainand tells me to look at the deep carving on the pole his grandsons are about to raise, a pole that at that very moment is being carried up the street toward the totem park in the arms of fifty men. It is late July, and Morrisons community of Hydaburg, Alaska, is replacing some of the aging totem poles in their Depression-era park as the finale to Haida Culture Camp, an annual celebration of the indigenous culture of the Kaigani (or Alaskan) Haida. Kids who have spent the week studying cedar bark weaving, halibut hook baiting, and X aad Klthe endangered Haida languagenow ride four-wheelers beside the men who carry the great cedar pole from the carving shed to the totem park, while women sing and drum to encourage them on. (One pole, carved by a woman named Toni Rae Sanderson, will be carried by women, with men singing them forward.)

The pole that Morrisons grandsons carved for the Hydaburg Totem Park is a replica of a 1930s pole that itself was a replica of a nineteenth-century pole from the Haida village of Howkan. Its crests of owl and killer whale recall the story of a Haida ancestor who was transformed into an owl; when I get a closer look, I see the sharp cleft of the owls beak and the teeth of the killer whale chiseled hard into the cedarthe deep carving that Morrison esteems. (We didnt always carve like that in the 30s, he tells me.) When the totem pole reaches the park, city crews tie ropes to the top, and long lines of people take the ropes in hand to heave the pole to its vertical position. Morrison watches the pole swing skyward and lock into place, and then, like everyone else, he breaks into applause.

P.1 .Raising a new version of the Owl-Human Transformation pole in the Hydaburg Totem Park, July 2009. A totem pole that dates from the New Deal period stands at back right. Photo by Emily Moore.

The Hydaburg Totem Park is not traditional to the Haida community. It is one of six parks built between 1938 and 1942 as part of a relief program during the Great Depression, when the federal government paid Tlingit and Haida men like Morrison two dollars a day to restore nineteenth-century totem poles from their ancestral Native villages and erect the poles in totem parks, where tourists could more easily see them. The Hydaburg parks strict rows of inward-facing totem poles look more like a sculpture garden than a nineteenth-century display of totem poles in a Haida village, where poles would have stood in front of clan houses, facing the beach. But if the totem park is a twentieth-century inventiona New Deal effort to bring tourist dollars to Native communitiesit is also central to Hydaburgs celebration of being Haida in the twenty-first century.

At the feast in the high school gymnasium that follows the totem pole raising, Tony Christianson, the mayor of Hydaburg, tells the audience that the totem park is

The story Tony Christianson tells about the Hydaburg Totem Park, or the pride Mijuu Morrison feels for his grandsons carving for the park, is not recounted in many books. It was not a story that I knew fully, either, when I began writing about the New Deal totem parks as a graduate student in art history. I had grown up in Ketchikan, Alaska, home to two other parks built in the late 1930s, and like many non-Natives in Southeast Alaska I had watched totem pole raisings in the parks and had Native friends who danced and carved in the parks for tourists in the summer. I knew that the totem parks were important to Tlingit and Haida communities, but it was not until I studied the origins of the parks in the late 1930s and interviewed Tlingit and Haida elders who remembered the parks construction that I began to understand the depth of their significance. Most scholars have dismissed Alaskas 1930s-era totem parks as inauthentic tourist arts invented by federal bureaucrats and devoid of meaning for Haida and Tlingit people. But this dismissal ignores the importance of these totem parks to Native communities in the 1940sas well as today. Overlooking the story of the New Deal totem parks also misses the motivations behind an important act of federal patronage for Native American artone of the largest acts of federal patronage for Native art in the twentieth centuryand the degree to which Tlingit and Haida communities participated in and actively shaped this government program for their own cultural and political needs.