Publication of this book is made possible in part by the proceeds of a permanent endowment created with the assistance of a Challenge Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency.

Manufactured in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper.

Preface

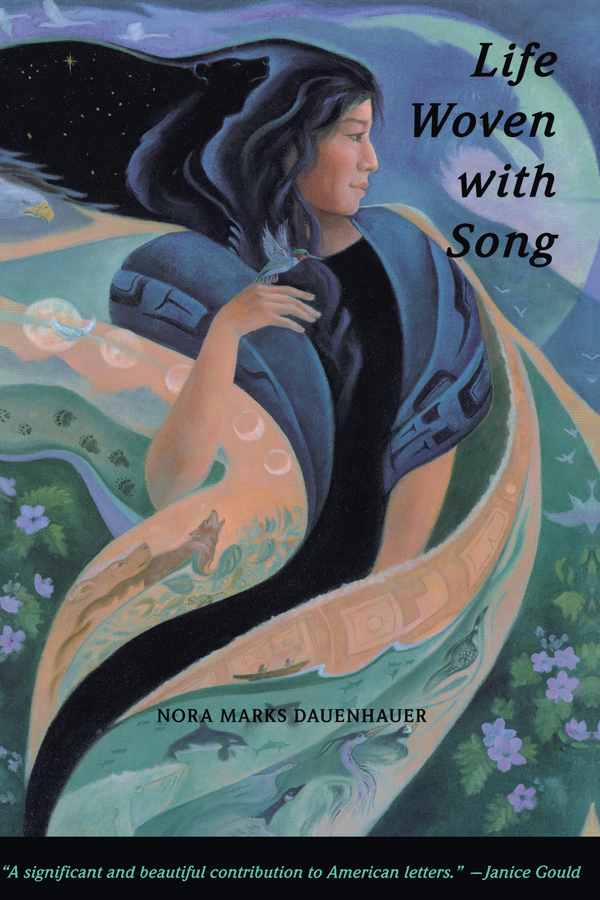

In this book are snippets of me and my family in the contexts in which we workedwork we enjoyed doing and work we did to keep alive. There are memories of my father trolling, trolling with his entire family, or the entire family in dryfish camp; of making a living in a cash economy by working in canneries; of my grandfather when he could no longer see; of my Auntie Jennie when she started to train me to be a grandmother; of a favorite basketball player; and of Tlingit elders. Memories of seasons, and of stories that were told at many places: in clan houses, in hunting and trapping camps.

Not all of the memories are of childhood. Many of my poems are of new images and memories of my grandchildren. I think that everyone is left with memories of their heritage, and these memories continue to teach us. They are a gift that keeps giving. In a way, this is what my writing is, my poems, plays, and prose. My family left me these images and memories, and I would like to keep them alive.

Most of the memories recalled here are happy ones. Where the images are neutral, negative, or discouraging, I like to think that they reflect our ability to continue as individuals, as a family, as a community, as a people.

People often ask me about my work, so Ill answer some of the most common questions here, anticipating that readers may be wondering about these things. Id like to say a few words here about the style and themes of my poetry and prose (comments on the plays are presented as a separate introduction to that section of the book). In gathering together my work of many years for this collection, it was interesting for me to see several themes unfold. There are the recurring themes of food and land, salmon and therain forest. The treatment may be serious or silly (as in the Raven plays), but the themes are there. In editing for this collection, I discovered how the themes are explored from different perspectives (from my point of view as a child, as a mother, as a grandmother) and through different literary forms (as poems, stories, plays, and autobiographical pieces). I guess they are all ultimately autobiographical. I hope the separate pieces come together for readers to form a larger cultural and literary landscape.

Readers reactions to my story Egg Boat vary. Some people like it a lot, others not at all. In Egg Boat and in some of the other prose pieces, I am trying to handle character, conflict, and dialogue in a different way. I am bothered by the endless chatter of TV sitcoms and of much childrens literature. I am trying for a more quiet inner dialogue, and for conflict not among the characters, but within the individual, as the individual finds himself or herself in the natural and cultural environment, in this case me as a twelve-year-old girl fishing the North Pacific for the first time alone. As one Tlingit high school girl recently said in describing her first experience in a traditional fish camp with elders, designed to complement the analytical elements of the school science curriculum, I learned to find courage in myself, and I learned to trust others.

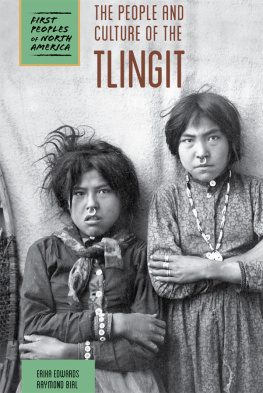

Now, a word about the setting. The work in this collection is mostly about home, but some of it is inspired by places I visit, whether elsewhere in Alaska, elsewhere in the United States, or elsewhere in the world. Whats home for me may be exotic to others. Like most Tlingit Indians, I live in southeast Alaska, in the middle of the largest temperate rain forest in the world, extending from northern California to Kodiak Island. Our part of this is an archipelago about the same size and shape as Florida. Few towns are connected by roads, so we travel by air, boat, and state ferry. Igloos and dogsleds are images from farther north in Alaska. We are the people of totem poles, Chilkat blankets, carved wooden hats and helmets, bentwood boxes, oceangoing canoes, and other products of the coastal rain forest. Our lives have traditionally been oriented toward beaches and boats. Once, on the Tohono Oodhamreservation in the Sonoran Desert of southern Arizona, I asked the kids how many of them had been in a boat. Not one. How about horses? All the hands shot up! Most of our kids have never seen or ridden a real horse. My first time on horseback was a trail ride on the beach at Neah Bay led by a teenage Makah girl. Native Americans are not all the same. Because some of the lifestyle and language of southeast Alaska may not be familiar to readers elsewhere, I have included a glossary at the end.

Finally, I would like to thank Ofelia Zepeda, Patti Hartmann, and the other editors at Sun Tracks and the University of Arizona Press for their faith in this book and for their patience during its delivery. Thanks also to my husband, Dick, who word-processed the manuscript and offered encouragement and advice along the way. He is also the photographer for the photos in this book that are not otherwise credited.

Some Slices of Salmon

ENTERING THE SALMON STREAM

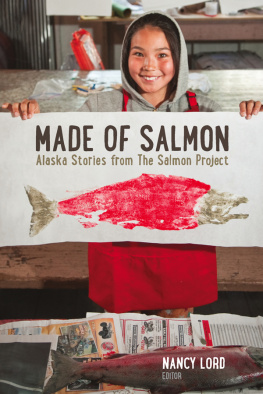

The first European and Euro-American explorers to southeast Alaska found us Tlingits in various places drying salmon. We Tlingit have always been eating salmon.

There are five species of salmon in Alaska: king, or Chinook, which is the largest; sockeye, or red; coho, or silver; chum, or dog salmon; and humpy (humpback), or pink. Salmon eggs hatch in fresh water; salmon spend most of their developing years in salt water and return to their home stream during the summer months to spawn and die. During this phase, their color and shape change dramatically.

Not only have we always used salmon as our main diet, and not only has it been the mainstay of our subsistence and commercial economies, but the different varieties of salmon are a part of our social structure and ethnic identity as well. Beyond the physical use of salmon as food, salmon have symbolic and totemic value. Many clans have salmon as their crest. My clan is called Lukaax.di in Tlingit; the name derives from a salmon river in Duncan Canal near Petersburg, Alaska. Our principal emblem is the sockeye or red salmon.

The Luknax.di clan derives its Tlingit name from another place of origin, related to the Tlingit word for coho salmon, which is their principal crest. The Leineid clan has the dog salmon as its crest, and the Kwaashkikwaan use the humpy or humpback salmon. Increasingly, most Tlingit clans are becoming known by the English names of their principal crest animal; thus the above-mentionedgroups are commonly called Sockeye Clan, Coho Clan, Dog Salmon Clan, and so on.