This book is for my cousin Rod Griffin

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Without Paul Holsingers courage and wonderful mechanical ability, this adventure could never have happened. The fact that he has had to wait 25 years to see it in print is a testament to his amazing patience. I needed that much time to understand the significance of the many relics of First Nations culture we stumbled upon as we meandered up this wild coastline.

When I was struggling with the research, it was my cousin Rod who answered my queries with 12-page handwritten accounts of the coast he knows so well from having ventured into its every nook and cranny and worked in both the logging and fishing industries. His memories could fill several books beyond the three that I have written.

But when all is said and done, it is my editor, Audrey McClellan, who deserves the greatest accolade, for without her skilful trimming and tidying, this book may have become no more than a longwinded travelogue. I hope it brings my readers as much satisfaction as the writing of it has brought me.

A final note: To retain the flavour of the time when I made the trip described in this book, I refer to places by the names they had a quarter-century ago and use terms that were acceptable at that time.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

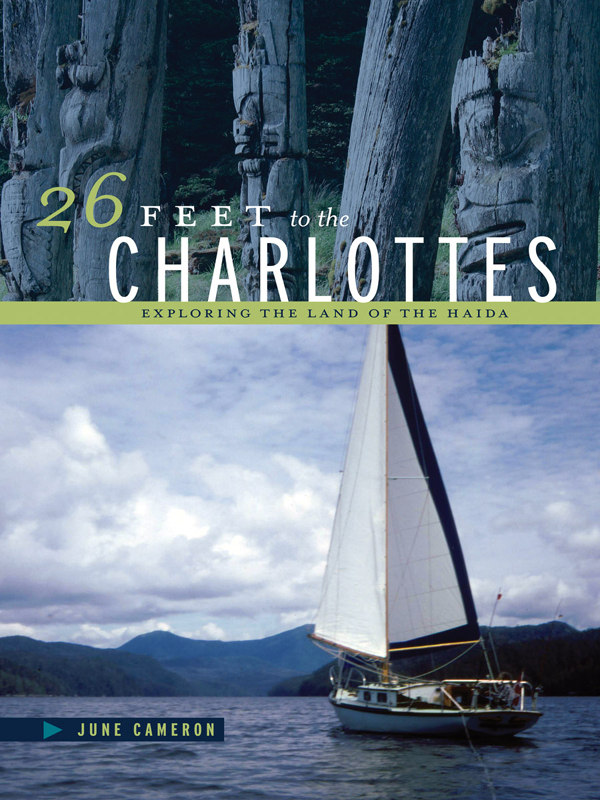

We were 13 days out of Vancouver on our way to the Queen Charlotte Islands, just about to leave the sheltered waters of the Inside Passage for a crossing of treacherous Hecate Strait, when a vicious northwesterly gale stalled us. This nasty bit of weather kept us holed up for three days in an uninspiring cove in the lee of Pitt Island.

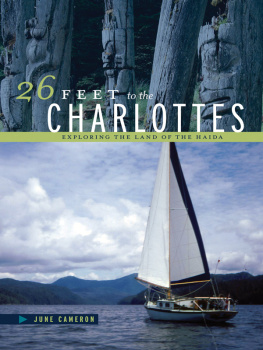

On the fourth day, the wind moderated and we ventured out. It felt good to be beating our way upcoast again. We were sailing. The sun was shining. What more could a sailor ask? Fewer swells would have been nice, but the wind was down to around 15 knots, and our little wooden sloop, Wood Duck, blazed away with me at the helm and Paul tidying up lines and making things secure.

I was used to racing my own sailboat in worse weather, so this was no real challenge, although Pauls boat, with its full keel, handled differently than did my 24-foot San Juan with its short fin keel. But Wood Duck chewed purposefully into the waves. Whenever we were hit by a sudden gust, I spilled excess air by heading into the wind, and the boat straightened up. We both grinned at the progress we were making on our journey.

Then, with a crack, the forestay pulled loose from the bow of the boat and the genoa flew off to one side with a roar of flailing cloth. I instinctively turned the hull to follow the sail, thereby saving the mast.

We watched in horror as the writhing sail billowed ahead of us with the metal strap thrashing at the end. The mast was still standing and the mainsail pulled us forward drunkenly as we ran down the faces of the waves. The roller furling line still held one corner of the huge foresail, and the sheets (the ropes leading to the winches) held the other, so Paul let the sheets go to ease the strain and flatten out the sail while I clung to the helm, trying to keep the boat from turning broadside. We had to keep the nose downwind if we were to save the mast.

The following sea lifted our stern and whitecaps hissed as they boiled alongside. By the time the foot of Pitt Island was abeam, Paul had managed to haul the sail down and jury-rig a temporary headstay so we could tack into the shelter of the island and make our way back to the anchorage. The miracle was that he managed all this without going overboard.

In 1983, when Paul Holsinger and I set out to sail to the Queen Charlotte Islands in his old 26-foot wooden sloop, we knew that we were taking on a major challenge. But neither of us was aware of how much danger we actually faced. We had grown confident in our survival skills after spending the previous three summers exploring the BC coast as far north as Ocean Falls. We were a water-wise, compatible, middle-aged couple who shared, among other things, an interest in fishing and beachcombing. But all of our trips so far had been in fairly sheltered waters. All that was about to change.

In order to reach these offshore islands, we had to cross the notoriously dangerous Hecate Strait, with no chance of shelter for over 70 miles. This is not usually a problem in a fast boat if the skipper anticipates moderate weather, but it is a major undertaking in a small craft making only four and a half nautical miles per hour. Another problem was our lack of electronic navigational aides. They were either too expensive for our budget or had not yet been invented. In hindsight, I realize that ignorance was bliss. Not only were we unaware of the problems we faced, but we also lacked any real knowledge of what to expect once we arrived.

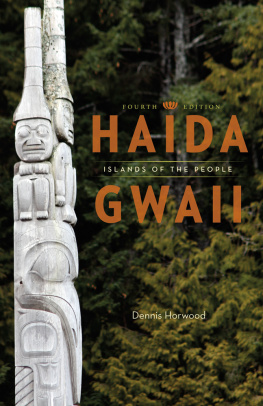

We knew that we would find none of the original settlements occupied, except perhaps Masset and Skidegate. And the people who lived there nowadays were likely thoroughly modern. But we wanted to visit old village sites so that we could get an idea of the challenges the original inhabitants had faced. When we finally reached the ancient village of Ninstints on Anthony Island, we discovered that collectors had taken the best of the carved poles, while rain and encroaching trees were doing their utmost to reclaim the rest. Even so, what we saw was enough to pique our interest in a culture that had produced haunting totem poles and unusual house structures in such an isolated place. The biggest mystery was how they had managed to keep warm, find food, preserve their history, stay healthy and just plain survive in this remote and unforgiving place.

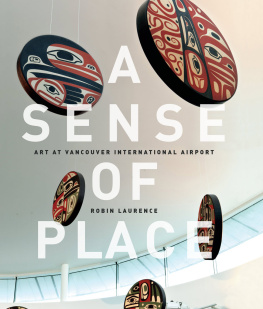

I kept careful diaries during our travels because I liked to read these accounts later, on rainy winter evenings. But at that stage of my life I had no idea that I would someday write a book about these adventures. As the years passed, curiosity kept me searching for information about the places we visited and about the indigenous people who had created the art forms we saw and those we could no longer see because they amounted to little more than bulges under the moss. Unlike the stone carvings in Europe, which had suffered from bombardment during wars, these artfully created cedar structures had mostly decayed and returned to the earth from which they came. Some had been removed to museums before they and the people they represented nearly vanished in the war between cultures that so decimated the civilization that created them.

With the arrival of the fur traders, the Native people had access to metal tools, cooking pots, foodstuffs and such things as rope and fishing tackle, so there was no longer the need to make things with cedar, yew or stone. Fortunately the craving for beauty did not die, but the need for money to purchase all these handy items drew many of these folk into the logging and fishing industries and also kept the artisans busy, for they had found a ready market amongst the newcomers for things like miniature totem poles carved from quick-hardening argillite, bracelets moulded from silver dollars, and baskets that were still being made by a few of the older women.

During our short visit in 1983, we were too far south to see the ugly naked hillsides that were the result of clear-cut logging. Current thinking by lumbering companies was that they should remove all growth and replant with just one kind of tree. All competing species were to be eliminated by spraying with herbicides. The erosion produced by road building and clear-cutting caused streams and rivers to silt up, killing the salmon fry. The Haida Nation and environmentalists from around the world began a vigorous campaign challenging these practices, and ultimately established Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site on Moresby Island.

Next page