Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

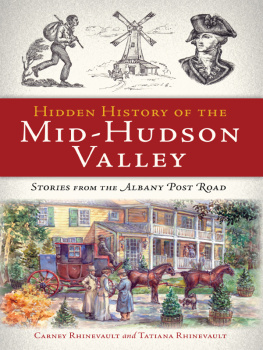

Copyright 2011 by Carney Rhinevault and Tatiana Rhinevault

All rights reserved

Cover image: Washington Irving stops at the Warren Tavern in Cold Spring, watercolor by Tatiana Rhinevault.

Illustrations by Tatiana Rhinevault.

First published 2011

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.100.1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rhinevault, Carney.

Hidden history of the mid-Hudson Valley : stories from the Albany Post Road / Carney Rhinevault and Tatiana Rhinevault.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-414-8

1. Hudson River Valley (N.Y. and N.J.)--History, Local--Anecdotes. 2. Hudson River Valley (N.Y. and N.J.)--Biography--Anecdotes. I. Rhinevault, Tatiana. II. Title.

F127.H8R48 2011

974.73--dc23

2011031267

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Dedicated to our son, Peter Vermeer Rhinevault.

Contents

His High Mightiness Is Wearing a Dress!

There is a legend that one night in the early 1700s, perhaps when there was a full moon, a drunken prostitute was spotted by a guard at the fort on the tip of Manhattan Island while she staggered along the dirt ramparts. It turned out to be no prostitute but was instead His High Mightiness Governor Edward Hyde (16611723), Lord Cornbury, fluffing around in a dress. He was immediately dragged out of sight by his own shamefaced soldiers. Alarm and confusion spread quickly from the forts guardhouse through the harbor docks and village streets, through the taverns and grog shops, through the darkened clapboard houses of tradesmen, through the brick and stone homes of old Dutch merchants and through the earth and dugout homes of poorer folk north of the stockade wall. House slaves quickly awakened from their beds on the floor to help the merchant ladies get dressed. What was going on? Was the governor drunk, or was an enemy attacking? Possibly the governor had lost his nerve and his mind. For todays confused reader, a little background information is in order.

Lord Cornbury, wearing his favorite dress.

THE FORT

The fort sat at the southerly tip of Manhattan (just north of todays Battery Park). Its construction was begun by the Dutch West India Company in 1612 and was completed in 1635. The Albany Post Road began at the fort and ended 156 miles to the north, at Albany. The fort was about the size of a modern football field and was the economic, political, military, cultural and religious center of the colony of Nieuw Nederlandts. The fort, originally named Fort Amsterdam, was renamed Fort James when the British took over the colony in 1664. It was then renamed Fort William, then Fort Anne and finally Fort George (obviously named after whoever was king or queen of England at the time). Its walls were made of dirt, and the four corner bastions were made of stone. Inside the fort were barracks for a 150-man military garrison, a guardhouse, the governors house, storehouses, an armory, a powder magazine and a stone church.

Wheat was milled by wind power.

The fort survived until the summer of 1789 after the American Revolution, when it was razed. The dirt walls were used for landfill in the Hudson shoreline, and the stone was used, in part, to build the Government House, intended for use by the three branches of the new federal government. However, the Government House stood unused for that purpose when our nations government moved back to Philadelphia in 1790 to await construction of the new capital at Washington, D.C. Instead, Governors George Clinton and John Jay used it as a residence, and it was used as a customhouse from 1799 until it burned down in 1815.

THE POST ROAD

The early history of the colony of Nieuw Nederlandts is really the history of two cities: Nieuw Amsterdam on Manhattan Island and Fort Nassau (Albany) farther north up the Hudson River (or North River, as it was called back then). Communication between the two cities (and the great estates, patroonships and tenant farms between them) was very sporadic and slow. A sailing vessel would take ten to twenty days to struggle from Manhattan to Albany. The Hudson River would freeze over in the winter, and travel by sail would come to a halt. No real roads existed on land, either. The Dutch colonists solved their communication problem in a most pragmatic way: letters would be collected at Fort Amsterdam, and then once a week or once a month a trusted Indian would run a pouch either up the river on ice or up the east side of the river on a footpath. Sometimes, but rarely, a healthy Dutchman would offer to be the mail carrier. We can fancy the lonesome post journeying alone up the solemn riverskating swiftly along, as a good son of a Hollander should, and longing every inch of the way for spring and the breaking-up of the river[or] sometimes climbing the icy Indian paths.

In the summer, a Lenape Indian, wearing the mail pouch, a cloth over his private parts, leather moccasins and not much more, would take off on a trot and head north through the small Dutch village. Soon he would be on the Mohican Trail and pass two Indian villages on Manhattan Island: Werpoes (near todays city hall) and an unnamed village at the caves of todays Inwood Park near 204th Street. Farther north, he would pass any one of a number of Indian villages: Napekamak (now Yonkers), a Weckweesgeek village at modern Dobbs Ferry, an Alipconck village at todays Tarrytown, a Hokohongus village at Sintsink (Stony Place or todays Ossining), the Senasqua village at todays Teller Point, the Meahagh village in the modern town of Cortlandt and on and on past perhaps ninety villages before reaching Fort Orange.

A 1702 Dutch home in New York City.

A hearty Indian could make seventy miles in a day, so an overnight would be made at Poughkeepsie, halfway between the forts. There is a legend that

a small kill sprang in an open woodland where the cattail weeds waved in the wind above the rockpool. Crossing the path the killetje rippled down a little glade, and fell into the HudsonMassanythe name of the stream that still splashes through the [Poughkeepsie] Rural Cemetery on its river bound courseHere, lay a station along the Indian runners path to the Manhattans, a rest place, where mats woven from the reeds [upuhki] hung upon bent saplings to form a lodge-covering, or serve as mattress on the damp ground. Doubtless from a tree branch above the water-place

Next page