PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

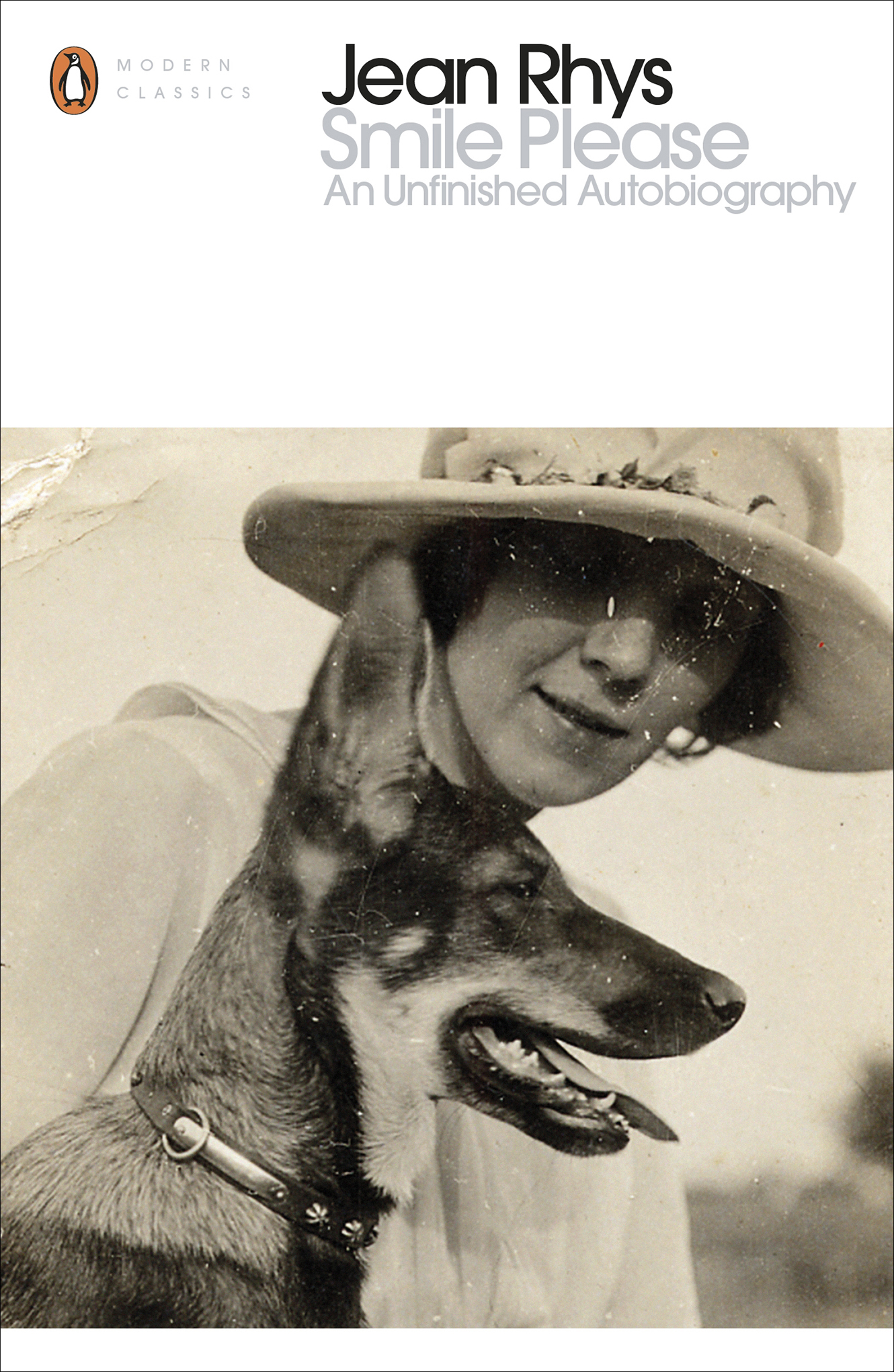

SMILE PLEASE

Jean Rhys was born in Dominica in 1890, the daughter of a Welsh doctor and a white Creole mother. She came to England when she was sixteen, where she trained as an actress and worked on chorus lines. In 1919 she married Jean Lenglet (Edward de Nve), with whom she lived on the Continent until their divorce in 1923. One child from the marriage survived. It was in Paris that she came under the influence of the novelist Ford Madox Ford, who encouraged her to write. Rhyss first book, a collection of stories called The Left Bank, was published in 1927. This was followed by Quartet (originally Postures, 1928), After Leaving Mr Mackenzie (1930), Voyage in the Dark (1934) and Good Morning, Midnight (1939). In 1932, she married Leslie Tilden-Smith, who was a reader with the publisher Hamish Hamilton and acted as her literary agent; he died in 1945. In 1947, she married Max Hamer, Leslies cousin. Max was convicted of fraud and as he was moved from prison to prison, Rhys followed him and disappeared from the literary scene. On his release, they moved to a cottage in Devon, where Rhys was rediscovered in 1958. She had begun work on a Dominica-based novel on her return from a visit there in 1936; despite poverty and ill-health, but with the support of her editor, Diana Athill, this would be published as Wide Sargasso Sea in 1966. The novel was Rhyss response to Jane Eyre and was a sensational comeback. It won literary prizes on publication and is today recognized as her masterpiece. Rhys wrote two further story collections, Tigers are Better-Looking (1968) and Sleep It Off Lady (1976). She died in 1979, and her unfinished autobiography, Smile Please, was published posthumously the same year.

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Andr Deutsch LTD 1979

Published in Penguin Classics 1990

Reissued 2016

Copyright The Estate of the late Jean Rhys, 1979

Foreword copyright Diana Athill, 1979

The moral right of the author has been asserted

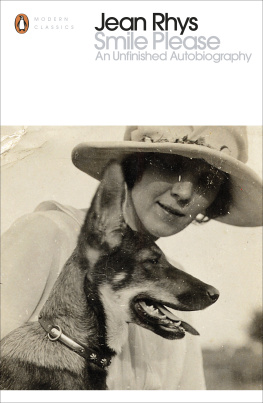

Cover photograph: Jean Rhys with a dog. Jean Rhys archive, Coll. no. 1976.011. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, McFarlin Library, The University of Tulsa. Tulsa, Oklahoma.

ISBN: 978-0-241-28555-8

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinUKbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

Jean Rhys and her Autobiography: a Foreword by Diana Athill

Jean Rhys began to think of writing an autobiographical book several years before her death on May 14, 1979. The idea did not attract her but because she was sometimes angered and hurt by what other people wrote about her she wanted to get the facts down.

This was not the kind of writing which came to her naturally. When she wrote a novel it was because she had no choice, and she did it or it happened to her for herself, not for others, in that it was at least partly therapeutic. She describes her first experience of the process in this book and it continued to work more or less like that... with the addition of a great deal of slow, meticulous and entirely conscious work which is not described in the chapter Worlds End and a Beginning because on that particular novel it was still to come. A novel, once it had possessed her, would dictate its own shape and atmosphere, and she could rely on her infallible instinct to tell her what her people would say and do within its framework. In a factual account she would have to rely on memory, not instinct, and this alarmed her. Her honesty was uncommonly strict, so she felt that the only dialogue she could use in such a book would be that which she was perfectly sure she remembered exactly. Except in a few instances, how could she be sure?

A graver problem was that much of her life had already been used up in the novels. They were not autobiographical in every detail, as readers sometimes suppose, but autobiographical they were, and their therapeutic function was the purging of unhappiness. Asked during a radio interview whether she had come to hate men, Jean Rhys replied in a shocked voice Oh no! The interviewer said this surprised him because most of the unhappiness in her life must have come from men. Jean answered that perhaps the reason was that the sad parts of her life had been written out. Once something had been written out, she said, it was done with and one could start again from the beginning. Much of the material she would have to consider in an autobiographical book had been disposed of in this way, so that raking over its remains would be unbearably tedious.

The solution towards which she slowly worked her way was that she would not attempt a continuous narrative but would catch the past here and there, at points where it happened to crystallise into vignettes. The stories in Sleep It Off, Lady, and their arrangement in chronological order, were an approach to this method, although it was only after they had been written that she saw they could be so treated. Three years before her death she began deliberately to pursue vignettes for the present book.

By that time she was eighty-six and old age was treating her harshly. She had a heart condition which made her quickly exhausted by any kind of effort, so that she could work only for an hour or two at a time, with long intervals between sessions; and her hands were so crippled that it was almost impossible for her to use a pen. A tape-recorder seemed to her an actively hostile device, so there was nothing for it but dictating to a person very difficult for someone as private as Jean Rhys. Fortunately she was able to find sympathetic helpers, none more so than her friend David Plante, the novelist. During the winters of 1976, 1977 and 1978, which she spent (as she usually did) in London, he devoted a great deal of time, tact and affectionate concern to taking down her words, typing them out, discussing them and reading them back to her for revision. She also accepted advice from him on the arrangement of some of the material. Without him she could not have completed the first part of the book, as she did. Nor would she have begun to put the material for the second part in order.

The first part is the account of her childhood in Dominica to which she gave the title Smile Please. In it the vignettes link up, so that it amounts to an impressionistic picture of those years as a whole, rather than to scenes from them. And from the early part of the books fragmentary continuation it can be seen that she was moving away from vignettes, towards continuous narrative, as she went on.