THE BLUE HOUR

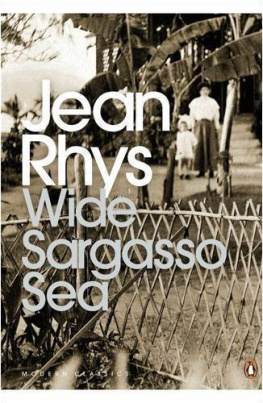

A Life of Jean Rhys

LILIAN PIZZICHINI

Copyright 2009 by Lilian Pizzichini

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pizzichini, Lilian, 1965

The blue hour: a life of Jean Rhys / Lilian Pizzichini.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-07939-5

1. Rhys, Jean. 2. Novelists, English20th centuryBibliography. I. Title.

PR6035.H96Z84 2009

823.912dc22

[B] 2008052919

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For Dolly and Rita

CONTENTS

Like is of all the words the most ridiculous with which to express the love that I have for this place, love that has something almost physical about it so that in moments of pain I have quite literally lain full length and drawn solace from the ground.

Elizabeth Garner, Duet in Discord

There is nothing unusual in all this, except to those who live like exiles in grey shadows.

Phyllis Allfrey, The Orchid House

Foreword

I n the summer of 1912 the French parfumier Jacques Guerlain concocted a scent from musk and rose de Bulgarie with a single note of jasmine. He intended his new scent, which he called LHeure Bleue, to evoke dusk in the city. The blue hour is the time when heliotropes and irises in Parisian window boxes are bathed in a blue light and the well-groomed Parisienne prepares for the evening.

For the novelist Jean Rhys, the blue hour was also the hour when the lap-dog she saw herself as being during the day turned into a wolf. Dogs hunt best during twilight. Underneath our surface sophistication lurks a predator. Jean Rhys was always concerned with what lay beneath the top notes. In Quartet , her first novel, set in Paris, a young female character, smarter and bolder than her heroine, is wearing LHeure Bleue by Guerlain. Rhyss heroine absorbs the womans scent as though in breathing it in she can capture her rivals self-possession.

The scent itself is dusky, as though bought from an old-world apothecary on a forgotten street in Paris. Its hints of pastry and almonds make LHeure Bleue a melancholic fragrance, as though in mourning for a time passed by. The curves of the Art Nouveau bottle, the stopper, in the form of a hollowed-out heart, allude to the romance of the years leading to the First World War. The story Jean Rhys told in Quartet describes the last days and weeks of a relationship, the loss of love and safety, and, implicitly, the death of old Europe. LHeure Bleue was her favourite perfume, and The Blue Hour is an attempt to re-capture her life.

O n 25 February 1936, Jean Rhys boarded a French ship called the Cuba at Southampton dock. The ship was bound for Dominica, her childhood home, which she had left twenty-nine years previously. Since then, she had lived in London, Paris and Vienna; she had married twice and given birth to two children (the first died in infancy, the second was living with her ex-husband). She had published a volume of short stories entitled The Left Bank , a translation of a French thriller, Perversity , and three novels, Quartet , After Leaving Mr Mackenzie and Voyage in the Dark . She had received critical acclaim, albeit somewhat guarded, and very little financial reward.

Going home was a matter of urgency: she had to go home to keep writing. She had moved through scenes of Parisian and London life like a sponge, soaking up the atmosphere and detail, yet so absorbed in her own travails that she was unable to connect with external reality. She had met famous people and been the lover of two English gentlemen, one a famous novelist. She had been disappointed and cast aside. She had been cut adrift from her roots, and had found no haven. Dominica was calling her home.

Jean was accompanied by her second husband, Leslie Tilden Smith, an occasional literary agent and publishers reader. The couples families came to see them off at Southampton: Leslies daughter Anne, Jeans sisters, and her long-lost brother Owen, who had recently returned from a failed fruit farm in Australia. He was as feckless as herself. Everyone brought flowers for the happy couple and everyone was happy for Jean. So was she; at forty-six years old, she was going home.

But the journey was hindered by the sea: the Sargasso Sea, where the Cuba seemed to flounder for long, dreary days in a mess of weed and wreckage. The sea itself was blocking her way.

The Cuba had a French crew and French and English passengers. Jean and Leslie had a table on the French side of the dining room. Jean liked French people. Unfortunately, the reality of being surrounded by people overcame her initial delight at their nationality. And they were not all French. Sitting next to her at the dining table was a voluble Italian woman with two noisy children and a thunderous husband. The womans chatter enraged Jean. Words were exchanged, the Italian glowered, an atmosphere poisoned the nightly meal.

Close proximity to other people wiped her out, erased her. It is so hard to get what you want in this life. Everything and everyone conspires to stop you. This was how it seemed to Jean. She could not voice her feelings, and her life, as she told it to others, seemed unreal. She often found that when she told people her story, they looked at her with disbelief in their eyes. So she stopped telling them. Instead, she told it to herself in her novels. That way, she at least could believe it. As a writer, this strategy worked well for her; as a woman, it did not.

Jean put on different guises for different phases, becoming a different person depending on whom she was with; there was no continuity to her idea of herself. When surrounded by others, it was a battle to preserve even the most subtle sense of who she might be.

Jean created her own world as protection from this one, with its infuriating chatterboxes, selfish drama queens, and arrogant upstarts. When she argued with her neighbours, as she would for the rest of her life, it was not merely a matter of winning or losing an argument, it was a struggle to prove that she existed.

The Cuba stopped at St Lucia for a week. The last time Jean had stayed on this comparatively sophisticated French island was for her Uncle Actons wedding. Acton was dead now. His widow, Evelina, and her two daughters Lily and Monica Lockhart, were running the Hotel St Antoine outside Castries. There had been a son, Don, who had shot himself. Volatility was not unheard of in Jeans family. On both her mothers and fathers sides there were instances of consuming despair and depression. Jean recognised something of her younger self in her cousin Lily, who was a bit of a loner. She went for walks by herself in the moonlight, and edited a self-published magazine for which she wrote all the stories. Leslie, an experienced man of letters, could see no merit in Lilys magazine, Jean wrote in a letter to a friend. But Jean liked it. She struck up a friendship with the girl, a rare instance of mutual sympathy in Jeans family.

The couples stay in St Lucia was pleasant. They were waited on by a woman dressed in the old style, the foulard and madras of the gwan wobe ( grande robe ) of the French Antilles. The woman brought in Jeans afternoon tea on a tray. It was, she said, the past majestically walking in.