Armand-Jean du Plessis did not hold the title de Richelieu before he could inherit the family estate from his brother Henri, who passed away in 1619. We shall already name him Richelieu for the sake of clarity.

Bloomsbury USA

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

1385 Broadway

New York

NY 10018

USA | 50 Bedford Square

London

WC1B 3DP

UK |

www.bloomsbury.com

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2011

This electronic edition published 2011

Jean-Vincent Blanchard, 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

ISBN: ePub: 978-0-8027-7853-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events, and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

Bloomsbury books may be purchased for business or promotional use. For information on bulk purchases please contact Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at .

CONTENTS

I.

II.

III.

10.

Il ma fait trop de bien pour en dire du mal

Il ma fait trop de mal pour en dire du bien

PIERRE CORNEILLE

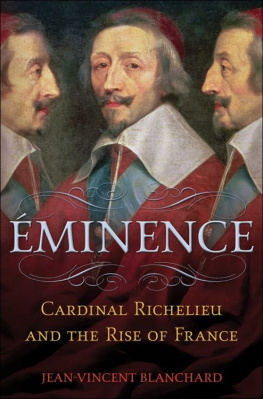

Take a look at his portrait. See the poised authority of the statesman, the gaze that stares back with lucid intelligence, and maybe a touch of bemused irony, as if he had just been asked a question ignorant of the magnitude of his responsibilities, the immense task of making France a powerful and prestigious land. Notice the blue ribbon and cross of the Order of the Holy Ghost, elegant gesture of the hand, the studied theatricality of the dcor.

These are not just effects born under the flattering paintbrush of the painter Philippe de Champaigne. Armand-Jean du PlessisCardinal Richelieus full namewas a leader of the government of France, a chief of diplomacy, and a war commander. Born in 1585, he became a cardinal of the Catholic Church in 1622, and then Duc de Richelieu in 1631, in recognition of his outstanding service as principal minister to King Louis XIII, the father of the Sun King, Louis XIV. Among the many exploits that earned Richelieu elevation and fame was the 1628 siege of La Rochelle, where he subdued those French Protestants who threatened the political unity of the kingdom. His career at the service of the French king continued for many years, during which he untangled the intrigues of the high nobility, and fought the hegemonic ambitions of the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs. For generations, the French have learned that the cardinal strengthened the monarchy, shaped the character of their nation, and was a crucial actor in a chaotic conflict, the Thirty Years War, out of which modern Europe emerged.

Few statesmen can claim a greater impact on history. Richelieu was the father of the modern state system, asserts Henry Kissinger in his opus, Diplomacy .

Such was his daring statesmanship. Then there was Richelieus style. One contemporary observed: In all fairness, this man had great qualities. He carried himself with high poise and in the manner of a grand sire, he spoke agreeably and with amazing ease, his mind was focused and worked with subtle ease, his general manner was noble, his ability to handle business inconceivably adroit, and finally he put a grace in what he did and said that ravished everyone.

Nevertheless, any reader who is familiar with Alexandre Dumass epic The Three Musketeers might ask about another side of the man: the disquieting Richelieu for whom the ends justified the means. To his detractors, indeed, the cardinals realpolitik appeared to be a betrayal of higher ideals of justice, French tradition, and morality. They decried his network of spies and secret police, viewed his trials as political shams, and lamented how his administrators in the kingdoms provinces enacted his iron will with no concern for local tradition. The punishments Richelieu meted out against those whom he considered threats to the power of the king were often violent, and many thought that this rigor represented brutality more than justice and exemplarity. Other critics argued that the cardinal took advantage of Louis XIIIs feeble nature and quashed any dissent in a relentless quest for personal power. The man would show no mercy toward enemies of the state, and the states enemies were his own. Richelieu seemed high-strung, harsh, and vindictive. A diplomat described his fits of wrath as canine. Cardinal de Retz, another priest-politician of his time, put it bluntly: He struck down humans like lightning rather than governing them. The scandal, of course, was even worse when these critics thought he used his moral authority to cover political and personal crimes. Guy Patin, one of Richelieus contemporaries, called him the red tyrant: the scarlet color of the cardinals robe, instead of signaling that he stood ready to shed his blood for the love of humanity, had come to represent the blood of his victims.

How did Cardinal Richelieu govern with a principle of human rationality, a reason of state, while still thinking that he was doing Gods work? Did character influence his decisions, and were his personal ambitions truly limitless? The historian who wishes to answer these questions faces many challenges. Because Richelieu promised Louis XIII early on that he would use all the resources necessary, and the authority that he would care to give [him], to ruin the Huguenots party, to humble the high nobility, to bring all the subjects to know their duty, and to raise his name in all the foreign nations up to where it should be, nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century French historians often readily recognized a sense of purpose throughout his career. It is always crucial, however, to beware of hindsight in writing a biography, especially in the case of a man who always took great care of how his own life and legacy would be perceived by posterity.

Richelieu died in 1642. Consider, then, that it took six years of skillful diplomacy for his successor, Giulio Mazarini, to ratify the Treaties of Westphalia that terminated the Thirty Years War (1648), and eleven years of military action to sign the Treaty of the Pyrenees that brought a satisfying conclusion to Frances war with Spain (1659). Consider, last but not least, that France was roiled from 1648 to 1652 by a civil war known as the Fronde. How is it that we consider Richelieus political action to have been so decisive, and having laid such firm foundations for French power? Even those contemporaries of the cardinal who did not hate him with a passion could still hold a surprising, if not dim, view on the real outcomes of his ministerial career. Surely they were less susceptible to hindsight than we are. The memoirist Claude de Bourdeille de Montrsor squarely attributed the few successes he was willing to recognize in Richelieus endeavors to sheer luck: Cardinal Richelieus enterprises owed much more to good fortune than the state owed to his counsel and prudence. One can marvel at how many times fate helped Richelieu, when, for example, Gustavus Adolphus lost his life at the Battle of Ltzen, just as the Swedish king was turning out to be an unreliable ally, and even a threat to the cardinals grand design for a European balance of power. At the very least, telling the life of Richelieu is to find out what political genius really is. It could well be, as expected, a superlative sense of prudence, doubling with an ability to manipulate emotions, notably by deft management of appearances. Or could it be something entirely different, a force whose nature makes it difficult to capture the essence of Richelieus action and legacy?

Next page